Twenty years ago leaders from across the globe convened in Durban, South Africa, to address the insidious effects of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance.

The World Conference against Racism, as it was known, led to the adoption of the Durban Declaration and Program of Action—a comprehensive and visionary document that laid out a global commitment against racism in all its forms and manifestations. The document is unprecedented because of monumental declarations that the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and slavery were crimes against humanity and support for reparations.

The 20th anniversary of the Durban conference was center stage Sept. 22 during the 76th United Nations General Assembly in New York. But the anniversary was marred by mixed feelings, controversy, and pressure on world leaders to boycott the session by Jewish organizations and the Zionist state of Israel, who falsely charged the Durban declaration was anti-Semitic.

Analysts said the Jewish claim of anti-Semitism was absolutely unfounded.

“That was never the issue,” said Roger Wareham, human rights attorney with the December 12th Movement International Secretariat based in New York. The group deals with issues of justice inside of the United States and often joins or connects with international bodies and organizations.

The issue became a very convenient scapegoat, Atty. Wareham added.

“The issue around the World Conference and Durban Program of Action was always about reparations,” he explained.

Placing the issues of reparations and slavery as a crime against humanity on the world stage was problematic for America, the attorney continued. The declaration placed America in a precarious position to seriously have to answer for her 400-year treachery against her Black once slaves.

The move was historic, said Atty. Wareham. People had brought the question of Black genocide to the UN before, but the declaration of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and slavery as crimes against humanity was a major achievement.

“Once something is declared a crime against humanity, there’s no statute of limitation,” he said.

If a legal venue to bring a suit for reparations as a crime could be found, America has no grounds to get the suit thrown out based on the age of the crime, said advocates.

Western nations like the United Kingdom and America who waxed rich from Black bodies and blood through colonialism and slavery joined Israel in boycotting the 2001 conference and the 2021 anniversary session.

The demands for boycotting stemmed from Jewish leaders still irate over the 2001 declaration that recognized Palestinians as a victimized group by the Israeli settler state and criticized Israel for implementing an apartheid system against Palestinians.

In 2001, the American and the Israeli delegations walked out of the conference in protest. Israel detested language comparing it to an apartheid regime like South Africa.

Sitting out uncomfortable conferences dealing with race is not new for America, nor is solidarity with Israel.

Before 2001, America boycotted previous UN conferences on racism—in 1978 and 1983—for precisely the same reason. The 1978 declaration proclaimed its “solidarity with the Palestinian people in their struggle for liberation.”

“The reason why Israel hooked up with the United States and vice versa was because of the Palestinian question,” said Dr. Ray Winbush, director of the Urban Institute at Morgan State University. He attended the Durban conference in 2001.

Palestine was supportive of Black demands for reparations and the United States didn’t want that, said Dr. Winbush.

Durban 2001 was a win

Atty. Wareham said the key to getting these items passed at the conference was international consensus and uniting around the positions. It was unprecedented for delegations representing Africa, the Caribbean, Central and South America and Australia to unite on a common agenda while being affected by racism as individual regions in different ways.

They agreed to put forward a three-point agenda declaration—the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, slavery, and colonialism were crimes against humanity and reparations were due the victims’ descendants, and lastly to recognize the economic basis of racism.

Durban goals were sidelined

The outcomes of the World Conference on Racism 2001 in Durbin were immediately attacked, torpedoed, and then hidden for two decades.

The U.S. did not want to deal with accountability for its wretched legacy of enslavement as a crime against humanity. And Israelis wanted no negative word about their actions and abuses.

Momentum was also sidelined because on Sept. 11, 2001, three days after the conference, came the attacks on New York’s World Trade Center killing 3,000 people. Shock and horror set in, followed by U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and a global war on terror. These things grabbed headlines, gobbled up funding, changed world and government outlooks, dragged the UN into the U.S. military adventures, and helped bury what happened in Durban.

“Its importance got diminished because two days after we got back there was the attack on 9/11,” recalled Atty. Wareham.

Atty. Wareham said the UN Human Rights Secretariat, influenced by the West, did little to publicize the Durban Declaration and Program of Action. And that’s “why most people have never seen it or read it,” he said.

When talked about, the meeting was misrepresented and Colin Powell, then U.S. secretary of state, Israeli officials and others boycotting, walking out, and condemning the conference were highlighted. Lost was not only the call for reparations, the slavery declaration and condemnation of Israel, but also the calls for justice for the Dalits, the Black untouchables of India; ending discrimination against the Roma, or gypsies in Europe, and demands for an end to the oppression, attacks and killing of different ethnic and minority groups in different parts of the world.

Instead of the conference serving as a launch pad for global combat against these ills and wrongs, there was no truly global focus and the evils of racism, discrimination and xenophobia have continued. The UN has, at times, called out these wrongs but not effectively dealt with them.

Whites as a global minority always feared people of color—particularly Black people—”taking over,” said Dr. Winbush. That was the fear at the World Conference Against Racism and remains today’s fear, he added.

Non-White nations seeking self-determination and different alliances—such Barbados seeking to exit the UK Commonwealth and Africa forging stronger ties with China—Europe losing economic power and America in chaos after four years of Donald Trump have stoked these fears, said Dr. Winbush.

“I think we’re going to see White people becoming more desperate and they will blame it on people of color as we see the treatment of the Haitians at the southern border,” he predicted. He is not confident America will change and told The Final Call it’s time for Blacks to sober up and chart their own course for survival.

Subsequent World Conferences Against Racism documented crimes perpetuated against the darker people of the earth in a day of manifest loss for America and her European brethren. In addition to other global voices urging an end to racism, xenophobia and discrimination, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam has warned the nations of the earth of the need to correct their wrongs and support Black progress.

“I am saying to the troubled world, help put Black people, the Black man and woman of America, into his and her proper and rightful place, and God will remove your headaches,” said Min. Farrakhan in a Sept. 7 column in The Final Call newspaper.

“Don’t continue the wrong, correct it and you will come into the Forgiveness and the Mercy of Allah,” he wrote.

The Minister has spoken about repairing the damage Black people incurred from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. All who were involved in the act of stripping Black humanity must be accountable to correct the wrong, he said.

Worsening conditions since 2001

“When we were in Durban 20 years ago, we had a lot of hope leaving there,” said Dr. Ray Winbush, who came to South Africa from the United States. “The African delegation achieved a lot of work at the conference. Durban will go down in history for when the Black and Brown world united to raise reparations and their historical victimization as a crime against humanity.

“There’s a lot of resistance,” he continued, speaking of conditions in 2021. “In the past 20 years, I think race relations has gotten worse rather than better.”

Since 2001 and the Durban Review in 2009, racial inequality, animus and xenophobia grew worse in America.

An August 2021 Pew Research poll of U.S. adults on racial trends indicated the public is “deeply divided” over how far the nation has progressed in addressing racial inequality.

Answering questions about a national reckoning with the history of slavery and racism in the U.S., 75 percent of Blacks polled said increased public attention is good and 54 percent said it is “very good” for society. Asian Americans, 64 percent, and Hispanics, 59 percent, agreed. Among Whites, only 46 percent agreed, and about a third said greater attention to that history is bad.

Along with the overarching question of America’s “original sin” is the lingering impact of racial violations and crimes. Racial disparities in education and a schoolhouse to prison pipeline exists along with incredibly high Black incarceration rates. NAACP figures say Blacks are five times as likely to be incarcerated as Whites and are an oversized percentage of the prison population—Blacks are 33 percent of prisoners but just 12 percent of the total U.S. population.

Shocking health statistics show Blacks at the top of the list of major health conditions, including Covid-19.

America has lost trillions of dollars in wealth through discriminatory practices against Blacks, said a September 2020 report, “Closing The Racial Inequality Gaps—The Economic Cost of Black Inequality in the U.S.”

“A plethora of data, studies, and societal ills indicate the U.S. has yet to achieve the point of racial equity, given the prevalence of major gaps in economic opportunity, education, income, housing, and wealth that run along racial fault lines,” said the report.

Among its other findings:

Peak income occurs sooner and is lower for Black males (age 45-49, $43,859) versus White males (age 50-54, $66,250).

White families have eight times as much wealth as Black families and lower debt-to-asset ratios. If racial gaps had been corrected, 770,000 new Black homeowners could have been produced.

More Black students with university and advanced degrees could have generated an additional $90 billion to $113 billion in U.S. income.

More than 6 million jobs per year might have been added and $13 trillion in cumulative revenue gained if Black-owned firms had equitable access to credit.

If the U.S. and Israel had not derailed the conference outcome, and worked to undermine the World Conference Against Racism, would the magnitude of issues adversely effecting Blacks still persist—and at the same level?

A 2009 document from the Durban Review reaffirmed the responsibility of governments to safeguard and protect the rights of individuals within their jurisdiction against crimes perpetrated by racist or xenophobic individuals, groups, or agents of the state such as law enforcement.

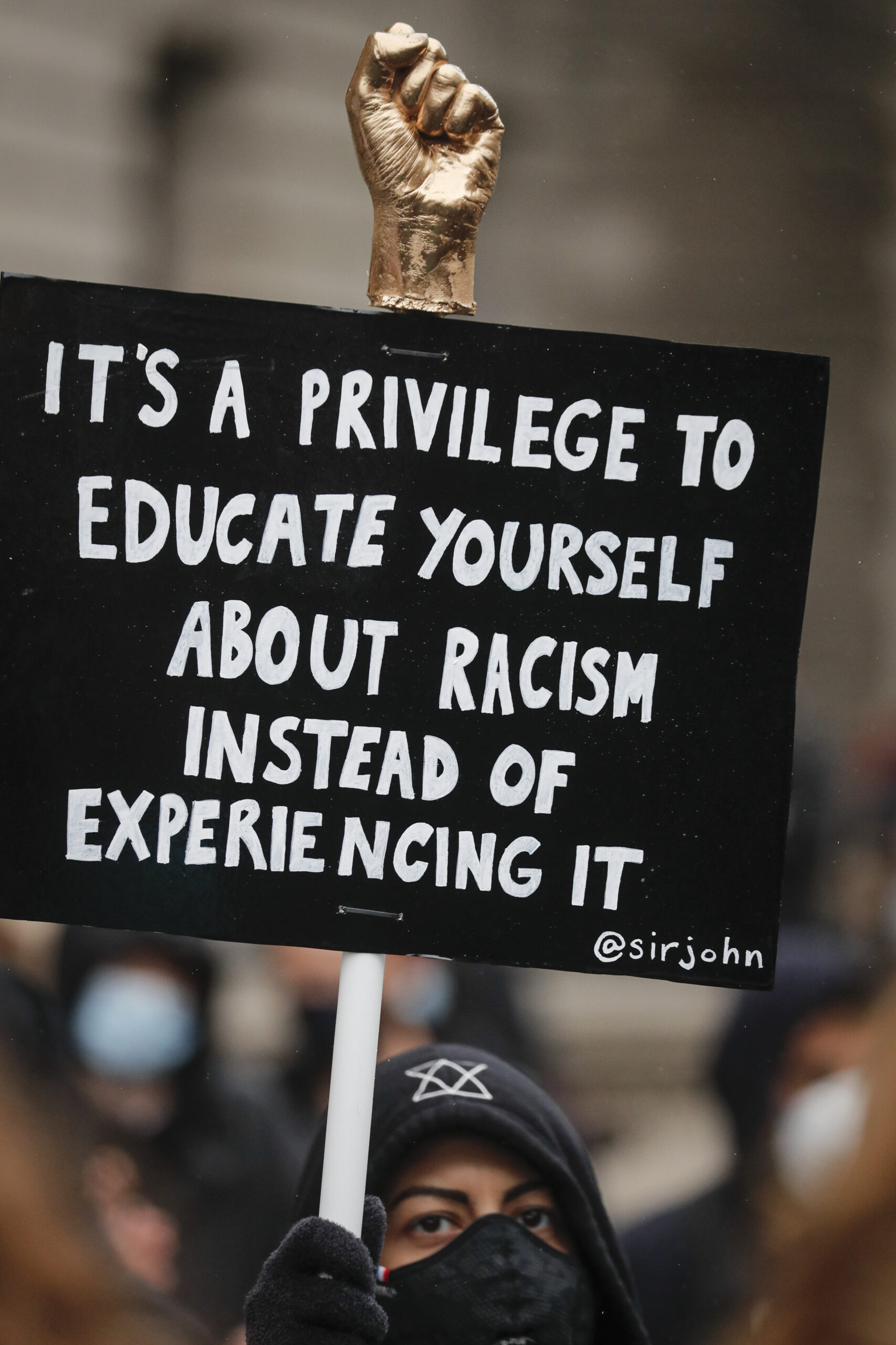

Statistics have shown a spike in White nationalism in America and in Europe, which is antithetical to the Durban declaration’s anti-racism and xenophobia agenda.

Federal Bureau of Investigation 2020 hate crimes data found with hate crimes 61.9 percent were racially/ethnically motivated and most known offenders, 55.2 percent, were White.

The images of Haitians violently turned away by U.S. patrols on the U.S. border with Mexico and sent back to an intensely troubled Haiti is an indicator of rising anti-immigration xenophobia against people of African descent, said activists.

Analysts say racism was rooted in America’s inception as a nation and is the cause of its resistance to squarely deal with racism’s historical aftermath.

Class conflicts among Whites and losses in status and incomes fuel anger among many poor and other Whites. That anger helps drive racial animosity towards Black Americans and hateful attitudes towards Black, Brown, and other non-White immigrants.

This underlying anger was seen in White reaction to the 2008 and 2012 election of Barack Obama, America’s first Black president, followed by the election of President Donald Trump as a champion of White grievance, animus and supremacy.

Dr. Winbush doesn’t believe Blacks fully comprehended the extent of these events as drivers of current racial hostility, resistance to reparations and righting past wrongs as outlined in the Durban declaration.

“I think that Black people underestimated how angry White people were when Barack Obama was elected. I think they’re still seething in that anger as evidenced by their support of Donald Trump,” said Dr. Winbush.

“You may see these pockets of ‘progress’ concerning reparations as the UN said, but at the same time I see more resistance to reparations, to Black people achieving things than I do progress,” Dr. Winbush said.

During a Sept. 22 plenary for the Durban commemoration at the United Nations headquarters in New York, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres reiterated how no country can claim to be free of racism and how racism is a global concern that must be tackled by a universal effort.

The president of the UN General Assembly, Abdulla Shahid from Maldives, said Durban I was not a failure although the goals of 2001 have yet to be fulfilled.

“Tackling racism and all its forms is a moral responsibility for justice,” said Mr. Shahid. “Racism begets violence, displacement, and inequity; it lives on because we allow it to,” he said.

Although the Durban declaration was not legally binding, it has strong moral value and serves as a basis for advocacy efforts worldwide.

Reparations and reparatory efforts were raised by Michelle Bachelet, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. “Reparations should be broad-based, and need to include measures aimed at restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition,” Ms. Bachelet noted in virtual remarks.

“These may include formal acknowledgment and apologies, memorialization and institutional and educational reforms. For reparations to be effective, all these elements are needed,” she said.

She added that reparations and reparatory justice must go “beyond symbolism” and require “political, human and financial capital.”

The costs should be considered in light of the enrichment of many economies from enslavement and exploitation, said the UN rights chief.

The 20th anniversary of the Durban declaration, together with its follow up processes and mechanisms, the “International Decade for People of African Descent,” the “Agenda Towards Transformative Change for Racial Justice and Equality” and “2030 Sustainable Development Agenda,” is a renewed opportunity to place racial equality and justice as the centerpiece of international, regional, and national agendas, said UN officials. Progress can be made if stakeholders stay united, they said.

“This is our common responsibility and duty—to past, present and future generations,” said Ilze Brands Kehris, assistant secretary‑general for human rights.