By Charlene Muhammad CHARLENEM

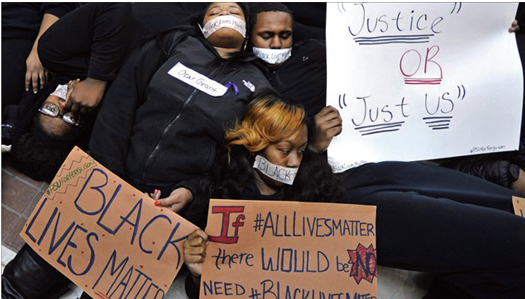

Controversial police officer-involved-shootings and other abuses across the country has spurred activists, grieving families and concerned citizens to continue the push for increased federal oversight in monitoring and enacting substantive changes in law enforcement practices on local levels.

But even when the U.S. government becomes involved, the question remains, do consent decrees and oversight of the police departments who violate the law even matter? What are the consequences, if any, for police departments that fail to adhere to these federal mandates?

According to some civil rights attorneys and legislators, there has been of good and bad in regulating police departments nationwide. Some victims’ families and police reform activists feel the government’s efforts toward justice have been a waste of time, money, and resources. These resources should be put elsewhere to solve the problem, they argue.

“First of all, all the laws from the government, period, don’t include us, so anything, I don’t care how they name it, since it doesn’t include us or protect us, it’s worthless to us,” stated Harry “Spike” Moss, who’s been fighting to end police brutality in Minnesota since 1966.

Consent decrees are effective, said Congresswoman Maxine Waters, adding that evidence has shown they have resulted in reductions in the overall use of force by police departments and improvements in police training on de-escalation.

As for improvements to the process, she told The Final Call, “First, we need an Administration and a Justice Department that cares about Civil Rights issues and is invested in police reform, and we don’t have that with Donald Trump and Jeff Sessions. Second, more can be done to look at how we ensure that police reforms and improvements that are made while consent decrees are in effect are long-term and last after the consent decrees are lifted.”

For instance, she stated, some data has indicated that, although there are dramatic reductions in litigation against police departments while the consent decree is in effect, that trend reverses once the decree is lifted. The federal oversight of a police department under a consent decree is meant to be temporary, but the police reforms need to be permanent, Congresswoman Waters added.

The U.S. Department of Justice began implementing federal consent decrees in 1997. It launched pattern-or practice investigations of police departments where institutional failures were seemingly contributing factors to police misconduct.

In 2001, a consent decree was used as an accountability measure on the Los Angeles Police, following a series of high profile incidents involving police shootings and heavy-handed tactics toward mostly Black citizens.

Among these incidents, included the nationally-publicized beating of Black motorist Rodney King and subsequent acquittal of the officers involved and the Rampart police division scandal, which exposed gang unit officers planting evidence, framing suspects, stealing drugs and money.

Cities or territories currently under a federal consent decree include: the Virgin Islands, Seattle, New Orleans, East Haven (Conn.), Puerto Rico, Portland, Warren (Ohio), Albuquerque, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department-Antelope Valley, Cleveland, Meridian (Miss.), Maricopa County (Arizona), Ferguson, and Newark, according to the Justice Department.

The way consent decrees function is the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division files civil lawsuits against police departments with patterns or practices of misconduct. Consent decrees are designed to look at systemic issues within police departments, such as complaints of constant, excessive force issues, racial profiling, training, and other misconduct problems.

Cases may go to a jury, but the majority of cities settle, and agree to correct specific problems within a certain time-frame. Since it began, the investigations and filings of the Justice Department’s cases against all but six cities ended in settlement without going to trial.

In addition to the Justice Department, state and local officials, as well as other entities also are involved. Those include organizations, advocates and activists from affected communities, who are a part of reporting whether police misconduct has gotten better or worse.

The federal government appoints independent monitors to track progress and compliance. Any violations trigger penalties outlined in the consent decrees, usually fines.

The Justice Department could press the issue of violations in court. Then a federal judge could hold individual officers accountable through criminal charges.When asked why the Justice Department has chosen the approach of consent decrees instead of prosecuting cops or police departments for their misconduct, Lauren Ehrsam, spokeswoman and Media Affairs Specialist invited the Final Call to its website to “look at the work that this administration has done using consent decrees, and said in regards to them.”

Ms. Ehrsam also provided a few press releases issued this April, but the question remained.

The LAPD consent decree was lifted in 2009 amid lots of dissatisfaction and disappointment in the community.

L.A.-based human rights lawyer Nana Gyamfi concurred with Mr. Moss, that decrees don’t matter when it comes to Black and Brown people. This is because police come out of the function of oppressing, attacking, and killing on behalf of the state, capitalism and White supremacy, she stated.

A police commission with various powers and structural changes within the LAPD came out of that consent decree, she noted. “But at the end of the day, three years running, it’s the most murderous police department in the country,” Atty. Gyamfi told The Final Call.

According to Atty. Gyamfi , the lack of real structural change is due to powerful police unions, and Black political leaders weakened by the financial backing they receive from those various unions throughout the country.

Because consent decrees are founded in lies, such as, “what we’re dealing with is just a few bad apples, that generally the police are wonderful and great people who mean no harm to the community …” it’s not producing any type of result other than the same result that we’ve seen before,” said Atty. Gyamfi

Uphill battle

In 2015, the U.N. Human Rights Council condemned the U.S. for human rights failures, particularly with regard to racism and police murders of Black men and boys.

“When you have that kind of laws and policies, we’re like road kill for them. … I’m almost convinced that the Nazis, the Skinheads, and the KKK (Ku Klux Klan) have told their membership to join law enforcement all over the country, because look how it’s changed from the 60s, how it has become that all of them have the spirit of those organizations,” Mr. Moss stated.

U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions has shown that apparently he doesn’t see any benefit in consent decrees, said civil rights lawyer Benjamin Crump. Mr. Sessions has said the federal misconduct lawsuits undermine respect for officers, and he’s ordered a sweeping review of 14 active federal consent decrees, which began under the Obama Administration.

Atty. Gen. Sessions said in a March 31 memo to staff that effective policing depends on local control and accountability. “It is not the responsibility of the federal government to manage non federal law enforcement,” he stated.

In Los Angeles County, reforms address a pattern of singling out people who receive federal housing subsidies for unconstitutional stops, searches, arrests and uses of force linked to community bias against people poor enough to qualify for such assistance.

Baltimore entered into a consent decree in Jan. 2017, nearly two years after the death of Freddie Gray in April 2015. A federal judge refused Atty. Gen. Sessions’ request to hold the decree for more time to review it, saying negotiations were over.

City officials are in the process of selecting the monitoring team which will track compliance for three years as set by the decree.

Investigators found police there exhibited a pattern or practice of systemic violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act, focusing on the failure to make reasonable accommodations when interacting with people with mental health disabilities.

“To me, to be honest, I’m so sick of all this reform talk, because at the end of the day, let’s be clear, this is a constant conspiracy to obstruct justice,” said Baltimore activist Tawanda Jones. “If they are doing criminal acts, they need criminal charges,” Ms. Jones told The Final Call.

Tyrone West, her brother, died in police custody on July 18, 2013. According to media reports police tackled him after a traffic stop, claiming he resisted arrest.

Ms. Jones maintains he was beaten. Maryland and Baltimore recently agreed to a joint $1 million settlement with his family. She said real accountability is for State Attorney Marilyn Mosby to reopen the case now that the civil suit is over.

The City of Ferguson in Missouri reluctantly entered into a consent decree last year, following the Aug. 2014 killing of Michael Brown, Jr. According to the Justice Department, it has missed critical deadlines, such as not setting up an operating independent civilian review board of the police department by Jan. 15. Ferguson officials said the work was hard, but that they’re further ahead than other cities under similar mandates and have made progress.

Penalties for violating consent decrees are supposed to range from revoked funding to criminal repercussions, such as holding officers and supervisors responsible, according to Atty. Crump. However, Ferguson has not been penalized. The chances are slim, he said.

“It’s really not set up for them to go to jail or anything, but it’s set to be a financial incentive or financial albatross for them, depending on if they comply with the consent decree,” Atty. Crump explained.

There were more consent decrees in Pres. Obama’s eight years in office than all other U.S. presidents combined, said Atty. Crump. Now, the consent decree doesn’t have nearly as much weight as it would have had under the last administration, he stated.

“It’s not surprising. Folks talk about how they’re yearning for the good ‘ole days when Eric Holder was attorney general and the federal government and the Department of Justice was more interested, allegedly, in addressing these issues with respect to police violence and state sanctioned violence at the hands of the police, when in fact, I think when if we look at what really has occurred, we haven’t seen a federal prosecution yet. … There’s not a single federal prosecution, out of all those murders of Black folks at the hands of the police,” Atty. Gyamfi said.

That was even with two Black attorney general’s during Pres. Obama’s two terms, including Mr. Holder and his predecessor Loretta Lynch, who served at the end of his administration, she added.

“I know a lot of times in the media it’s gloom and it’s doom, but you have to remember, in most of these federal agencies, at least from my understanding and my experience has been, you have a number of people who are there regardless of who the President of the United States is,” said Dwayne Crawford, executive director of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE).

He said he understands the rhetoric about being tough on crime and that his organization is finding that the work which began under the Obama Administration is continuing. According to Mr. Crawford, at least 18,000 agencies seem to be interested in continuing the police reform efforts begun in recent years.

“I’m not here to say that consent decrees are perfect. I’m not here to say they solve everything, but I am here to say that I really think that many of these agencies are trying their best to ensure one, community engagement, transparency, accountability … but I also want to say to everyone that there are men and women, both within the profession, within federal government, who are doing their best, in my mind, to continue these reform efforts,” Mr. Crawford told The Final Call.

The federal government can also check police misconduct through patterns and practice investigations which can result in federal mandates like the one brought by U.S. District Judge Thelton Henderson in Oakland, Calif., in 2003.

The city went under federal observation after four former officers in West Oakland were charged for misconduct ranging from planting drugs on, beating, and falsely arresting poor Black people. The case ended in a $10.9 million payout to 119 victims. Three of the officers, Matthew Hornung, Clarence Mabanag and Jude Siapno, were acquitted. The fourth, Frank Vazquez, fl ed the country, and remains a fugitive.

Oakland officials agreed to implement various reforms such as around training, and better investigating citizens complaints.

According to Atty. John Burris, a civil rights lawyer who helped bring the case, there’s something very positive about a consent decree, at least in terms of its objectives. But they don’t work without cooperation and accountability, he said.

Otherwise, consent decrees can go on indefinitely, as it has with the Oakland case, he said.

The problem is praising departments and police officers for making “some progress,” and then extending their time-frame for improvement, according to Cephus “Uncle Bobby” Johnson, whose nephew, Oscar Grant, III., was shot in the back by a former BART officer on a station platform in 2009.

Increasing crisis intervention training or requiring cops use body cameras haven’t brought justice, because at the same time, the killings, shootings, and violations continue, said Mr. Johnson stated.

“The policy and outlook of police work may have changed, but the actual culture of police work has not changed. The corruption that it has been known for still exist,” said Student Minister Keith Muhammad of Muhammad Mosque No. 26B in Oakland.