by Anisah Muhammad

Contributing Writer @MuhammadAnisah

When Tameka Drummer went to prison at the age of 34, her youngest child was only four years old. Her child is now 17. The 47-year-old Black mother of four is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. Her crime? Possessing less than two ounces of marijuana.

In the southern state of Mississippi, Black people are languishing in jail because of life sentences under unjust laws. Ms. Drummer served time for two violent felonies committed in the 1990s—voluntary manslaughter and aggravated assault—but she is still being punished under Mississippi’s habitual offender laws. She received her sentence in 2008 after being pulled over for an expired license plate in Alcorn County, Miss. Officers found marijuana in the car.

The state has two types of habitual offender laws: a “little” law and a “big” law. Under the little law, if a person commits three nonviolent felonies, they will receive the maximum possible sentence for the offense and could possibly get life.

Alicia Netterville, the deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Mississippi, explained that though the little law is not as harsh or abusive as the big law, it’s still not workable. The big law sentences people to life without the possibility of parole, even if the third crime isn’t violent.

“We have seen people who may have committed a violent crime 20, 30 years ago, served time for that. They’re out working, being productive citizens, raising families, and then they commit another felony that’s not violent, that can be related to marijuana possession, two grams of cocaine and then that person can be automatically sentenced to life without parole because they committed a violent crime 20, 30 years ago,” Ms. Netterville said.

She said it could be described similar to “three strikes and you’re out.” The federal three strikes crime bill was implemented under former President Bill Clinton in 1994. Working in conjunction with the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, the bill decimated Black communities and Black families. According to an article by the ACLU, following passage of the federal crime bill, incarceration rates continued to climb for an additional 14 years.

Today in Mississippi, 2,635 people are serving time in prison due to the habitual offender laws, according to state data. Of those, 250 people are serving 20-or-more-year sentences for nonviolent offenses, the majority being drug-related crimes. The data from the advocacy organization reports 78 people are serving 50 or more years for drug crimes, and 21 have been sentenced to die in prison for drug possession as a result of Mississippi’s habitual laws.

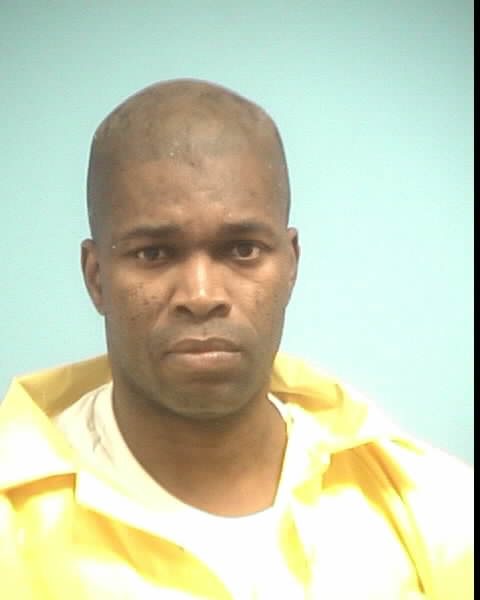

Black men are 13 percent of the state’s population and yet make up 75 percent of the people serving 20 or more years. One of those men is Russell Allen, who was denied appeal because of the “habitual offender” title. In May, a Mississippi Court of Appeals upheld his life sentence. Similar to Ms. Drummer, Russell Allen’s third crime was possession of more than 30 grams of marijuana. The 38 year old was found guilty in 2019.

Mississippi’s southern neighbor, Louisiana, also has a habitual offender law. Under Louisiana’s law, Derek Harris, a Black military veteran, was sentenced to life in prison for the sale of less than $30 of marijuana. He was released in Aug. 2020 after serving nine years.

Black women represent more than 50 percent of women who are serving life sentences in Mississippi, according to a report by the National Black Women’s Justice Institute, the Sentencing Project and the Cornell Law School. Nationally, one out of every 39 Black women in prison is serving life without parole, compared to one out of every 59 White women.

Dr. McKinney voiced her frustration over Ms. Drummer’s case, noting that marijuana has been legalized and decriminalized in many states across the country.

“How many states have decriminalized marijuana and making it something that you can’t be arrested for? And how many states now have actually legalized it, where you can go to a dispensary and buy it whether you have a medical need or not?” she questioned. “We now understand that marijuana possession should never have been something that we were incarcerating people for. And yet, here’s a woman who is serving a life without parole sentence because she had marijuana. What is wrong with our country?”

Mississippi legislators passed the Parole Eligibility Act, or Bill 2795, in April, but “best of all,” the state’s Republican Governor Tate Reeves tweeted, “habitual offenders are not included in this bill.” In Aug. 2020, he declared he would not pardon Tameka Drummer after a change.org petition was started and her case garnered advocates.

“As it was going through the political process, advocates pushed for people who were convicted under habitual laws to be included in 2795. But it didn’t make it through the political process, and it’s not the first time that a failure to relax the habitual law has happened in our state,” Ms. Netterville said.

She said the state’s extreme laws and long incarceration rates are costing the state millions of dollars, funds that could be used for rehabilitation and reentry services.

“Even if you take someone who committed a violent crime 20 years ago and they have managed to work through all of the obstacles and barriers of reentry, to have a family, to have a job, and then having been snatched away from society that they’re contributing to because they shoplifted or because they had marijuana, less than two ounces or less than two grams of crack cocaine, that’s just nonsensical,” she said.

She explained that the problems in the carceral system can be traced back to the 13th Amendment. “As long as we view incarceration as slavery, which it technically is under the 13th Amendment, and we view incarcerated people as revenue generators instead of people who are incarcerated for a period of time to be rehabilitated, the desire will always be there to continually incarcerate long periods of time so that they can keep the plantation, for lack of a better term, operating,” she said.

Nation of Islam Jackson, Miss. Student Minister Abram Muhammad also described the incarceration system as a modern-day plantation. He said it also enslaves the family, as a large portion of Mississippi’s inmates are from other states, and a lot of people from Mississippi are incarcerated in other places as close as Florida and as far away as Arizona and Nevada.

“This creates a strain on the family, because how many families do we know have the economic wherewithal to be able to travel to and from these places to be able to visit their loved ones?” he asked. “So, this creates a detachment, a sense of being alone, not cared for, not loved.”

Referencing words from the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, he said the problems persist by design.

“Incarceration, vaccination, poor education, poor job, poor stores with food quality, things of that nature, it’s all designed to be able to make, in their mind, ‘America Great Again,’ which simply is coded for going back to how it used to be,” he said.

He said a spiritual solution, plus having a quality education, jobs, housing and food, would eliminate many of the crimes Black people find themselves locked up for.

Another solution Black people across the country have taken up is economic withdrawal from White-owned and operated companies, many of which invest in the prison-industrial complex. Black people are opting to no longer fund their own oppression and to instead, buy Black. Under the call of Minister Farrakhan, the Nation of Islam has been involved in a six-year economic boycott to “redistribute the pain.”

Student Minister Muhammad, who is working towards a doctoral in criminal justice, also talked about the need for social workers and for someone to be able to guide and steer a person’s mindset, activities and environment so that they see an alternative. He and Ms. Netterville said criminal justice reform will have to come from the people: both the people who have been impacted by the criminal legal system and those who have never been affected.

Dr. McKinney said the language “habitual offender” needs to be eradicated, as it doesn’t recognize how complex people are.

“It doesn’t recognize the growth that people go through over a period of time, especially the kind of growth and change that can happen in a person whose needs are being met and who are well and who are restored,” she said.

In comment to Ms. Drummer’s prior felonies, Dr. McKinney pointed out that many women who are incarcerated are incarcerated for crimes of survival, protecting themselves from harm.

“Incarceration is not the answer when we have all of these systems failing Black women. So, I think the thing that we need to be doing is investing in our communities, examining the ways in which the systems and institutions that govern our society are causing harm and try and build in and put in place new systems and new interventions and new ways of doing things and practices that support the healing and restoration of Black women in our communities,” she said. “That’s how we end and reduce. That’s how we keep Black women out of the criminal legal system.”