Five years ago, Freddie Gray, a young Black man in Baltimore, was arrested for allegedly possessing a knife. A few days later, he died from injuries to his spinal cord sustained during his arrest and transport. But police brutality and misconduct are not the only dangers to Black life.

As a boy, Freddie Gray lived in extreme poverty and thus was exposed to significant amounts of lead, according to a recent University of Georgia report on “Racism and the Contamination of Black Lives” published in the Journal of African American Studies. In 2008, Freddie Gray’s family filed a lawsuit against their landlord after he and his siblings showed they had significant blood levels of lead. He lived in a community saturated with underfunded schools and food deserts.

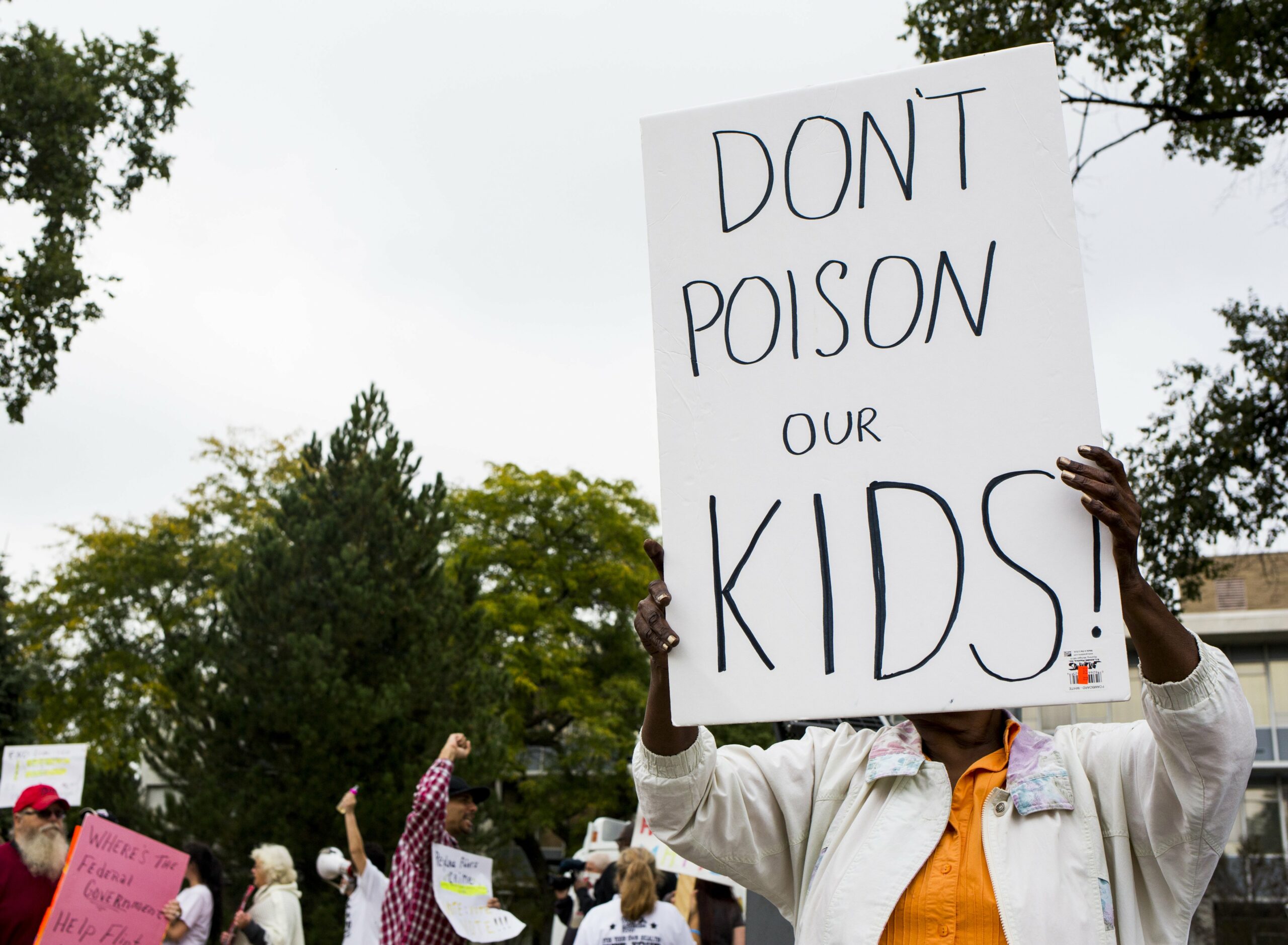

“Gray lived in a community where he was slowly being poisoned by lead during his developmental years, and his parents never got the help they needed despite the documented evidence of lead poisoning,” the report says. “Gray is not an outlier; he is an all too familiar example of the Black experience in the United States.”

The study found that environmental racism and exclusionary housing policies and practices such as redlining create health problems in Black communities. The writers break down the definition of racism and its different levels. Racism can manifest through stereotypes, prejudicial beliefs, or discrimination, it says. Specifically, it defines environmental racism as a form of structural racism.

“Structural racism is the policies and practices that normalize and legalize racism in a way that creates differential access to goods, services, and opportunities based on race,” the report says. “Environmental racism refers to policies, practices, or directives that result in advantages or disadvantages to individuals or communities based on race.” Furthermore, environmental racism includes harm caused by infrastructures that determine access and quality of resources and services.

“To understand environmental racism in the United States, we must discuss the nation’s history of housing policies and the ways they have impacted Black people,” the report says. Those policies include zoning ordinances, restrictive covenants, blockbusting, steering and redlining. It defines redlining as a practice used by the Federal Housing Administration to outline Black neighborhoods with red, making them ineligible for federally insured loans, according to the rating system used by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation.

Angela McIver, chief executive officer of the Fair Housing Rights Center in Southeastern Pennsylvania, looked at every redlining map in the United States because she wanted to understand why Black people suffer so much in their communities.

“Why are the social disparities so prevalent amongst us? And the deeper I dig into redlining, the more I see that in a large part from the 20th century into the 21st century, therein lies the problem,” she said. “And looking at all of those redlining maps, they have commonalities when it comes to the red section. Oftentimes they’re referred to as risky, hazardous or dangerous.

“Language that’s associated with us as people. Not as a status of our properties, but us as human beings,” she said.

She said the legacy and the practice of redlining is alive and well and that historically, Black people, Jews and Latinos were subjected to it. HOLC maps used a color-coded system, where green meant the neighborhood was best, blue was the next best, and yellow was declining. And then there was red.

“Today, if you take that 1937 redlining map of Philadelphia and you overlay that on a map that highlights all of our disparities, the wealth gap, the educational gap, health disparities, economics … access to resources, you will find that hardly anything changed from that 1937 map,” Ms. McIver said.

She said redlining still exists, but instead of physical maps being colored green or red, it’s done by zip code, neighborhood, algorithms and IP addresses.

“Where you sit from your home to attempt to do digital transactions, you’re being watched. They know exactly where your IP address is. And advertisements or the lack of will or will not come to you because of that,” she said. “Your zip code, when you put that into certain electronic platforms, will also steer you towards or away from things. It’s very widespread nowadays. So it went from being more low tech to high tech now.”

Ms. McIver explained that people are placed at-risk because of zip code.

“If we will look at one of my favorite zip codes to highlight in Philadelphia because it is in the heart of the redlining section, which is 19132. And you examine all the social determinants for 19132. It’s not because they’re bad people living in that zip code. It is because systemically over time people have not received fully all that they need,” she said.

She said redlining is an accumulation of things that happened in the past that haven’t been undone. “Where was the redress from there? Who got a check making them whole from that? It didn’t happen. But yet, people will shake their finger at folks who live in these neighborhoods and present the argument as if this is all on you,” she said. “And that’s not the case, the issue is that for the most part, we’re decent, kind people who are seeking peace and justice. We just haven’t revolted about all of this.”

Willie J.R. Fleming, co-founder and executive director of the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign, expounded on the idea of “death by zip code,” and he said most of the zip codes that fall under that phrase are Black communities.

“I say there’s a lack of police services in that community, there’s a lack of educational institutions in that community, there’s a lack of health facilities in the community. When I hear death by zip code, it makes me think about the food deserts,” he said.

According to 2014 research from Johns Hopkins University, racial health disparities could be due to differences in physical and social environments, including access to healthy food.

Mr. Fleming called Chicago’s efforts one of the biggest overhauls of public housing in the country, and it forced Black people into other communities. “One of the impacts of tearing down public housing in the country was we didn’t get rid of poverty,” he said. “We just relocated. We displaced poverty.”

He said housing discrimination means Section 8 housing choice vouchers being underutilized, and he explained that housing discrimination is rooted in American policy and that it’s not simply a housing crisis. “There’s a human rights crisis in America. This is not displacement. This is urban and economic cleansing,” he said.

“When we talk about housing discrimination, we talk about the ability for first time homeowners to access loans and lenders who will lend to them. And that’s when the terminology redlining comes in,” he said. “So we talk about discrimination on one aspect, that you can’t get a loan to buy a home. And then we talk about the aspect of not being able to not only get a loan, (but) not being able to get a loan in a particular community that’s non-African-American.”

He said housing discrimination not only applies to Black and Latino residents, but Black developers who want to develop affordable housing are also discriminated and redlined against.

In the University of Georgia report, the writers highlight three specific events to show the contamination of Black lives: toxic wells in Dickinson County, Tennessee; coke plants in North Birmingham, Alabama; and the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

Latinos on the Southeast side of Chicago are facing their own crisis. It started when a metal-shredding company that was accused of violating air pollution and nuisance laws moved operations from a majority White and affluent neighborhood to the Latino-majority Southeast neighborhood. Activists are undergoing a hunger strike to protest the relocation.

“If they’re removing that industry in order to revitalize that community, what does it do to the community you put it in? That means that community does not experience that revitalization. That community is going to suffer the health impacts that that industry creates. And it also affects property values,” said Peggy Salazar, director of the Southeast Environmental Task Force.

“We become victims,” she said. “And also, in some ways, it becomes normal, because that’s what they do over and over again, so we kind of start to begin to normalize it.”

Ms. Salazar said land use and zoning policies need to be changed and community investment needs to take place.

“We want some revitalization and investment here, not dumping things that other parts of the city don’t want,” she said.

Mr. Fleming explained that all levels of government need to take the Fair Housing Act seriously, that there has to be equal protection under the law and that there has to be a greater penalty for housing discrimination. Ms. McIver said there needs to be a full commitment to right the wrongs of the past and to address the needs of the people.

“We’re talking about man-made situations that have been superimposed on people who, again, for the most part, are kind and decent and loving and who have not revolted from this but who are patient and waiting on what they believe are other decent human beings to, with the stroke of a pen or other provisions, help to change these outcomes for them,” she said.