By Charlene Muhammad CHARLENEM

Of 5.8 million Americans with Alzheimer’s, Blacks know the least about the disease associated or marked primarily by memory loss, but are the most affected, experts say.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, based on data for Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older, Alzheimer’s or another dementia, a decline in mental ability, had been diagnosed in 10.3 percent of Whites, 12.2 percent of Hispanics and 13.8 percent of Blacks.

Part of it is because the Alzheimer’s is linked to diabetes and heart disease, which are prevalent in the Black community, they say.

“The myth in Black culture is mama and daddy, they’re getting old and they’re senile, so the word Alzheimer’s as a disease, that’s really a new word for us,” said Dr. Pernessa Seele, founder and CEO of the Balm in Gilead. The Maryland-based religious nonprofit promotes health education and disease prevention and management through the Brain Health Center which it opened for Blacks in 2015.

Alzheimer’s has been affecting Blacks for the many decades it’s been around, but in recent times Blacks have just begun to talk about it, she told The Final Call.

“We just knew it as mom and dad are old, and this is just a part of losing your memory and all the things that go along with having this disease is just a part of the aging process, but the reality is it is not a part of the aging process,” she said.

Health advocates say continuing education in the Black community is necessary, but that has proved challenging, because awareness, education and funding has not increased along with the number of Blacks who suffer from the disease.

“The public health system will say the dollars follow the numbers, but I’ve been in this business for 30 years, and I can truly say that the dollars do not follow the epidemic when it comes to Black folks,” stated Dr. Seele. She does think a lot of money is put into research, and clinical trials, but often times Blacks don’t participate, she and other health advocates noted.

“The medication that they’re researching is being tested on White men and not the people that really need it the most, so we need to become more engaged in these clinical studies, if you will,” Dr. Seele continued.

She advocates for more awareness, funding and treatment. “It’s just a fight all around!” she said.

“In the Black community we talk about Alzheimer’s as ‘Sometimer’s Disease.’ Sometimes we remember, sometimes we don’t. In the faith community we talk about we’ve gotta be in our right mind, so anything that you have that’s taking you out of that place, there’s a stigma attached to it, so there’s a lot to overcome,” Dr. Seele said.

“One of the biggest issues that we have as a community is lack of access to information about Alzheimer’s disease, and in terms of Alzheimer’s disease disparities, compared to Whites, African Americans are less likely to get a diagnosis, so we can die with the disease and will never have a diagnosis,” said Dr. Karen Lincoln, an associate professor at the USC School of Social Work and director of the USC Hartford Center of Excellence in Geriatric Social Work.

Alzheimer’s often exists simultaneously with other conditions, like diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and obesity, which puts people at greater risks.

“When you have chronic health conditions that doctors are typically trying to manage, they’re less likely to focus on Alzheimer’s,” said Dr. Lincoln.

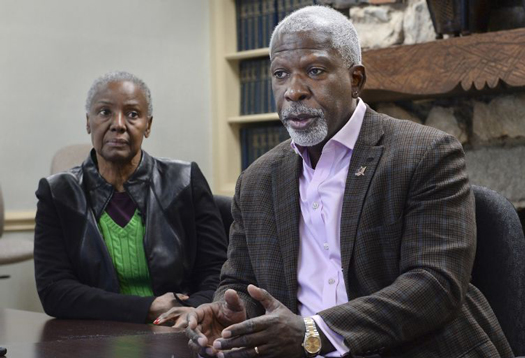

In cases of seniors like 76-year-old Eddie Muhammad, who wandered from his home in Carson, Calif., in early September, bullet shrapnel may have been a factor in his dementia diagnosis, according to his wife Charisse. He got shot nine times in 2012 protecting his family from an assailant in his home and one of the bullets is still in him. His doctor said it appeared he had a stroke and that may have had something to do with his dementia, she stated.

His memory loss and incoherence has gotten worse since last year, Charisse Muhammad stated. And he’s not capable of lengthy conversations anymore.

Nation of Islam Western Region Student FOI Captain Halim Muhammad and Muhammad Mosque No. 27 in Los Angeles led a manhunt along with Mosque No. 54 in Compton and surrounding areas, as well as L.A. County Sheriffs, who used scented dogs.

Eddie Muhammad was found at Centinela Hospital, approximately 14 miles and 30 minutes away in Inglewood.

“The day before (he went missing), the disaster that hit the Bahamas was on the news, and we were looking at the news and he had his burrito in his hand and he took it up to the TV and looked like he was ready to feed the people,” said Charisse Muhammad. “Just the impact of him not knowing that was real with the television program, and I couldn’t, it’s not like you can shake him and say that’s not real,” said Mrs. Muhammad.

She recently quit her job as a cosmetology school instructor and took another one she thought would give her more time with him.

“If anyone ever goes through this with their loved one, you just have to have the love for the person, because I also work at a convalescent home and I see people who have dementia,” said Charisse Muhammad.

She was overwhelmed by the support she received from Muslims, and thanked everyone for standing by her family and for their prayers, love and support.

Blacks facing Alzheimer’s often suffer serious challenges, not just in how the disease presents itself in families, but in caregiving, and as they have to stop working to care for a loved one, which is often not reimbursed, according to experts.

Make sure there is a diagnosis of dementia, which opens the way for services, resources, and necessities such as tracking devices, advised Dr. Lincoln. “One thing you don’t want to do, you do not want to lock them in the house. That’s elder abuse or abuse because of the dangers associated with locking someone in the home, whether it’s a child or whether it’s an older adult, and someone who wanders obviously needs to have care,” Dr. Lincoln said.

Adult day care centers and other facilities can care for dementia patients and allow caregivers to work, rest or take care of other family needs. But unfortunately, many Blacks can’t afford other options, said Dr. Lincoln. Nursing homes are the only type of longterm care facilities that Medicaid will pay for if one is poor, she explained.

Care is expensive. In Los Angeles, California, in general, and many other metropolitan areas paying $6,000 to $8,000 a month for assisted living is not unusual. Floridians may pay closer to $4,000, said Dr. Lincoln.

It’s also very tough for families to put loved ones suffering dementia into facilities with reports of elder abuse, neglect, even rape occurring in nursing home facilities, acknowledged experts.

“But to have that kind of care where someone can live in a clean environment and have skilled nursing available 24 hours a day, it’s terribly expensive and it’s out-of-pocket. So what our people typically end up having to do is locking people up in a garage or locking them up in a house, so that they can go to work or putting them in a nursing home that is low quality, because many of us want to keep our people close in our communities,” said Dr. Lincoln.

Once loved ones are diagnosed, she recommends getting assessments as soon as possible, starting treatment, and beginning to plan for care, before it’s too late, and there’s panic.

Finding medicines that work, addressing issues of housing, transportation, dealing with the financial impact of the disease, including caregivers’ loss of income, should be done, according to Stephanie Monroe, executive director of AfricanAmericansAgainstAlzheimer’s, and USAgainstAlzheimer’s network.

“These are really important issues that some would say really impact national security,” she told The Final Call.

Black and some other populations don’t seem to appreciate the importance of prevention strategies, but tend to wait until illness strikes, Ms. Monroe said. Some who qualify for Affordable Health Care Insurance, don’t go out and get it, and when they get it, they don’t know how to use it, she said. They’re not used to taking off time from work to go in for preventative check-ups, she added.

When they do go in, doctors fail to ask them about their brain health or memory. “They’re not doing tests that are available to even check how we’re doing at 30, 40, 50, so that when changes start to happen early, through detection, they can make the appropriate referrals and get us in to the help that we need,” said Ms. Monroe.