While the poverty rate for White non-Hispanic people is decreasing, the rate for Black people is increasing, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 recent report on poverty.

The Census Bureau uses two ways to measure poverty: the official poverty measure, which looks at income alone, and the supplemental poverty measure, which includes non-cash benefits like food stamps and subtracts necessary expenses like taxes.

The poverty rate for White non-Hispanic people declined in both measures. For Black people, it increased in both. White non-Hispanics had the lowest poverty rate of all races.

In both measures, Black people, American Indians and Alaska Natives and Hispanic people of any race had the highest poverty rates. These same three groups were also more overrepresented in the poverty population, according to the report, released in September.

Black people make up 13.5 percent of the country’s population but made up 21.8 percent of the poverty population in 2023.

“This country has to always maintain a low-income class of people. It’s in the system. It’s written into the way capitalism works, that you have to have some have-nots,” Elisabeth Omilami, CEO of the Atlanta-based organization Hosea Helps, said to The Final Call.

The causes and effects of poverty

Poverty is defined as “the state or condition of having little or no money, goods, or means of support.”

Low wages, unemployment, the lack of affordable housing, racism and discrimination, education and healthcare are some of the most common causes of poverty, according to Feeding America, a nationwide network of food banks, food pantries and local meal programs.

Poverty is associated with food insecurity, homelessness and poor health and education outcomes.

Donald Head Jr. experienced homelessness firsthand. His experience propelled him to work on homeless issues for nearly 30 years. Now, he is the executive director of the National Coalition for the Homeless based in Washington, D.C.

He linked the Black homeless population to structural racism and America’s historical mistreatment of Black people.

“Racism still exists, and you can discriminate against somebody based on their subsidy. You can’t do it because of the housing rights legislation. You can’t discriminate outright, but you certainly can discriminate via a subsidy,” he said to The Final Call.

One of the more alarming trends he has seen is the criminalization of homelessness.

“Because they have not addressed the structural, tougher issues, they’re resorting to just jailing; fining and ticketing people because of their homelessness, and the majority of those people are people of color,” he said.

“The most alarming part is it’s not the normal suspect. So, it’s not in conservative communities alone. It’s also in some of our ‘progressive’ communities; actually, more so in the progressive communities we’re seeing this reliance on a carceral approach to homelessness.”

He argued that the way to solve homelessness is affordable and low-income housing and better wages, not hiding people away in jail.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury released a report in June on “Rent, House Prices, and Demographics.” The report noted that for the past two decades, rent and house prices have been rising faster than incomes across most regions of the country.

“For some households, increased housing costs means there is less to spend on everything else, including food, health care, clothing, education, and retirement savings,” the report says.

“The affordability challenge is particularly severe for households of color and for low-income communities. Black and Hispanic households tend to spend higher shares of their incomes on housing expenses than White households.”

With the lack of affordable housing and better wages, “it’s impossible to keep up,” Mr. Head said.

He is an advocate for jobs that pay livable wages, for eviction-prevention programs and for better health care coverage. But ultimately, “we have to go back and undo the wrongs that happened during the Jim Crow era,

The chattel slavery era, and also even the New Deal era, when we didn’t provide the opportunity for people of color to generate wealth because of redlining and the lack of inclusion in VA (veterans affairs) programs,” he said.

“People cannot ignore the underlying racial practices that keep us in this situation, and we can’t just address the symptoms. We gotta go to the root, and the root is structural racism.”

Mapping poverty

The Center for American Progress, a public policy research organization, used U.S. Census data to rank all 50 states plus Washington D.C., on the official poverty rate, unemployment, income inequality, food insecurity and housing, amongst other categories.

Poverty is more concentrated in the South, with southern states Louisiana and Mississippi leading the way. In these states, the poverty rate is coupled with high-income inequality and high food insecurity.

In Georgia, longtime activist Elisabeth Omilami has helped people for over 30 years. As a teenager, she would help feed the hungry with Hosea Feed the Hungry, now called Hosea Helps. She has noticed that now, many people who show up for help are so-called middle-class.

“They are people presenting for services that never thought they would be in that situation,” she said. “The middle-class is truly being squeezed with the price of food, the interest on loans, gasoline, the cost it takes to even buy a house for a young couple.”

She noted the importance of filling the gap for the middle-class as well as those in a lower-income bracket, in order to keep the country from being run by monopolies.

Through Hosea Helps, Ms. Omilami runs the largest Black-owned food bank in the Southeast. The organization also helps with rental assistance, hotel stays for families living in cars and moving costs. It sees about 200 families a week.

She spoke on the importance of organizing in order to fight poverty.

“Solutions don’t lie in the government,” she said. “Really, it lies in an awakening in the broad community across the country that we have to take care of ourselves. Our churches have to participate. Our sororities, our fraternities.”

Western states like California and Nevada have high unemployment rates and suffer from a lack of affordable and available housing.

On the East Coast, New York has the ninth highest poverty rate, the sixth highest unemployment rate and the second highest income inequality, after Washington, D.C.

Rev. Robert Ennis Jackson described how many neighborhoods in New York City boast wealth, while a large number of people fight to stay above the poverty line. He pointed to Bedford-Stuyvesant as an example.

“You could live in a community that was predominantly Black called Bedford–Stuyvesant 20 years ago and be fighting the poverty line and now have Bedford-Stuyvesant as a rich quarter of Brooklyn, but still have a 24 percent poverty rate,” he said.

He co-founded the Brooklyn Rescue Mission Urban Harvest Center, which has been feeding people for over 20 years and now feeds 10,000 people a month.

He is an advocate for Black people controlling their own land, food sources and businesses to create economic stability. He also believes in reshaping the culture of the Black community back to one focused on education and family and teaching Black children their worth.

“Fighting poverty means empowering and building skills for people,” he said.

A voice for the poor

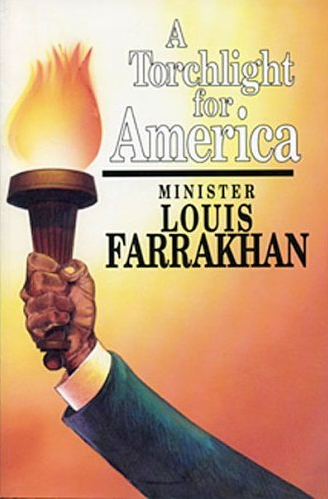

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, National Representative of the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad of the Nation of Islam, has been a longtime champion for the poor.

In his book, “A Torchlight for America,” on page 38 he writes about America’s “greed for short-term profit that has generated an entire society devoid of values and that alienates the poor and the few non-greedy.”

On page 39 he continues, “The American worker has worked and sacrificed to build this country. The corporations, the high-paying government jobs, the fine material possessions, all of this was built on the backs of slaves and the labor class,” he said.

“It is wrong for companies to leave the poor and the working classes in the lurch—conceding manufacturing to other nations under the guise that America is becoming a more service-oriented economy.”

Minister Farrakhan urged Black organizations and leadership to focus on self help. On page 40 in the section titled “The Mentality of Black Leadership,” he lays out guidance on what must be done.

“… Black leadership cannot go to the government to beg it to provide a future for us. Putting the beg on America is not a wise program for our leaders to advance on behalf of the people. That old slave mentality that keeps us at odds with one another and dependent on people has to be broken,” he said.

“Black leadership must champion the strategy of turning within to do for self. Meaning, we must teach our people to use our talent, time and money, and pool our resources educationally and financially, to address our troubles.”

“Whatever America decides to do, our actions cannot be dependent on the actions of a benevolent, White, former slave-master,” he added.

Minister Farrakhan acknowledged that while America owes Black people reparations, in the country’s present condition, “what she owes will stay on the back burner or not on the stove at all.”

“We must work harder to address our own problems. We must also provide the country with solutions that benefit us as well as the whole, to pull the country to a state of strength,” he writes. “Perhaps, when the country’s condition improves, we can speak more effectively about what is owed to us for our services, past and present, to repair our condition.”