In 1974 Ghana’s Asante royal family requested the United Kingdom script and pass legislation that would encourage the return of its looted treasures. The reply was “very racist and rude,” recalled author, filmmaker, and art historian, Nana Oforiatta Ayim.

The request was finally presented to the House of Lords. In response to the suggestion that sacred Ghanaian objects that embody the souls of ancestors, be returned to its rightful owners one Lords member said, according to parliamentary minutes, “Would it not be possible to keep the booty and return the souls?”

Another Lords member cautioned “warily when it comes to returning booty which we have collected,” that process could “turn into a strip-tease” of Britain’s museums.

The booty derived from this capture and plunder of West Africa’s Benin had been celebrated in American and British newspapers. British soldiers kept much of the treasures and valuable historic artifacts for themselves. To make matters worse, after they pillaged these sacred artifacts created specifically for ancestral alters, they donned fake native wear and wore blackface to reconstruct their lucrative exploit.

“The theft included Benin Bronzes, a collection made up of carved ivory, bronze and brass crafted sculptures and plaques. These were not mere artworks but catalogue the story of Benin—its achievements, explorations and belief systems,” according to an exhaustive study on looted African art commissioned by Al Jazeera.

This thievery was no less important than would be the pillaging of sacred artifacts connected to Christianity. Commissioned specifically for the ancestral alters of past Obas and Queen Mothers, the artifacts were also used in other rituals to honor the ancestors and to validate the accession of a new Oba (Yoruba ruler).

In fact, the pieces ended up in more than 160 museums globally. The largest collection, 928, is at the British Museum where an exhibition took place within months of the Benin kingdom being razed. Berlin’s Ethnological Museum holds 516, the second largest collection. There are 173 at the Weltmuseum in Vienna, 160 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) in New York, 160 at Cambridge University’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and 105 at Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum.

“It was purely a colonial power exerting power on the community. They looted and burned down everything and carted away what they took off the people,” Professor Abba Isa Tijani, of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments said.

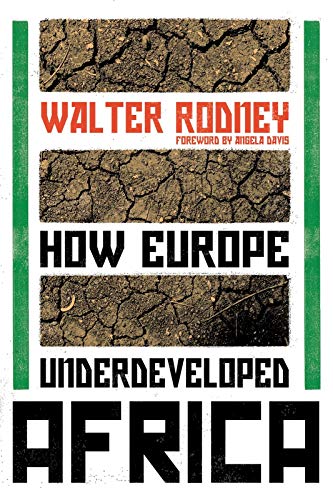

To put this transition between the European slave trade and the institutionalization of European imperialism in perspective we go to Dr. Walter Rodney’s historic book, “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa.”

Dr. Rodney’s thesis has assumed a foundational place in understanding the legacies of slavery and subsequent colonialism for the underdevelopment that unfolded over centuries on the continent. The core of his analysis rests on the assumption that Africa—far from standing outside the world system—has been crucial to the growth of capitalism in the West.

What Dr. Rodney terms “underdevelopment” was in fact the result of centuries of slavery, exploitation and imperialism. Booty was a relatively small wealth earner, like Nazi Germany looting European art works. Rodney explains that Europe and colonial and imperial powers did not merely enrich their own empires but reversed economic and social development in Africa. He explains how the West built immense industrial and colonial empires on the backs of African slave labor, devastating natural resources and African societies in the process.

One thing Africa 2021 represented is the heightened discussion of the repatriation of African artifacts. But as Dr. Rodney in his 1973 book explains: the more important issue is the resulting exploitation or underdevelopment of an entire continent and the resultant development, at the expense of Africa, of the Western world.

“The colonization of Africa lasted for just over 70 years in most parts of the continent. That is an extremely short period within the context of universal historical development. Yet, it was precisely in those years that in other parts of the world the rate of change was greater than ever before. As has been illustrated, capitalist countries revolutionized their technology to enter the nuclear age,” he explains in his book.

The discussion of the repatriation of Africa’s historic artifacts is an important one. But in the framework of Europe and U.S. imperialist interest, Africa’s “borrowing” of its stolen artifacts, and repatriating the estimated nearly 200,000 pieces, one-by-one, or telling looted African countries, our European countries laws prevent the return of what rightfully belongs to you, is nothing but stall tactics. Those precious objects they never plan on returning. Follow @JehronMuhammad on Twitter