Editor’s Note: This story is the first in an occasional series on the crisis of missing and murdered Black women and girls.

CHICAGO—Sensei Rasul Bey is on a mission to teach as many Black women and girls as possible how to defend themselves with martial arts. He offers discounted beginner classes to women and girls of any age on the South Side of Chicago.

It is important to protect and raise women up and the status of Black women needs to be higher, he said. Like many in Chicago and elsewhere, in his own way, he is seeking to address a crisis facing Black women and girls.

Unfortunately, not everyone has the self-defense skills, knowledge and ability to recognize and ward off or avoid threats, threats that are disproportionately impacting Black females.

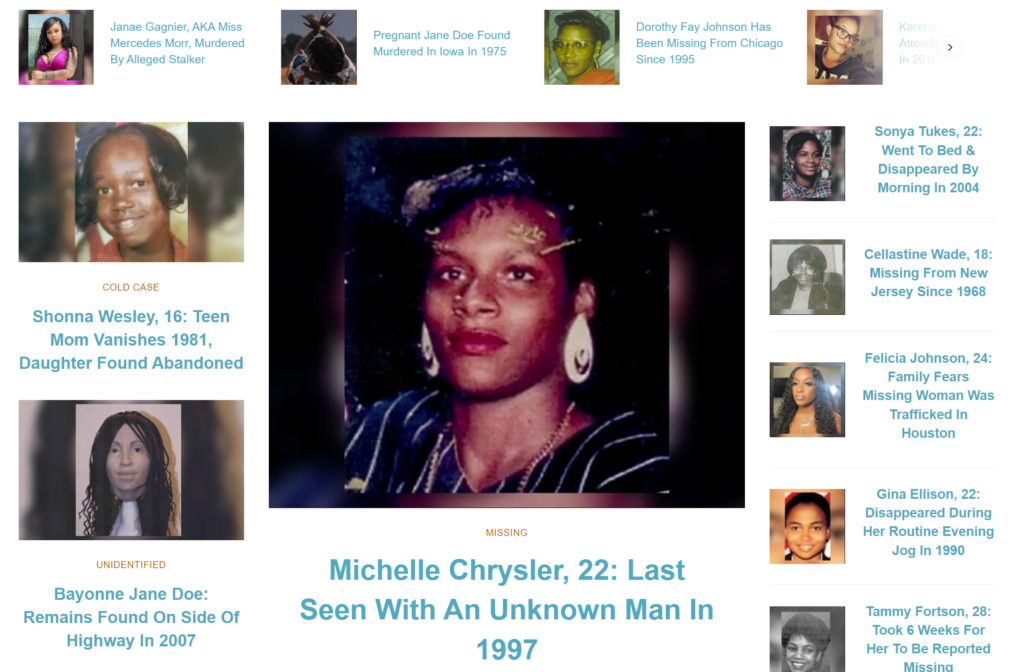

Erika Marie, a journalist and activist who launched the website Our Black Girls in 2018, created a database for missing Black women and girls nationwide whose faces do not appear often in the news. Her website, OurBlackGirls.com, is now trademarked and a nonprofit.

It is difficult to keep up with the numbers because of inaccurate reporting of these cases, she said. “The statistics regarding missing Black women that I use as reference come from the government’s public databases, but of course, they are fraught with errors as updates aren’t given as frequently as we all would hope,” she added.

According to the National Crime Information Center, Black women made up 90,299 out of the 521,705 missing people in the entire country in 2020. Within the same year, Black women and girls were being murdered at a rate of four each day, reported the Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer.

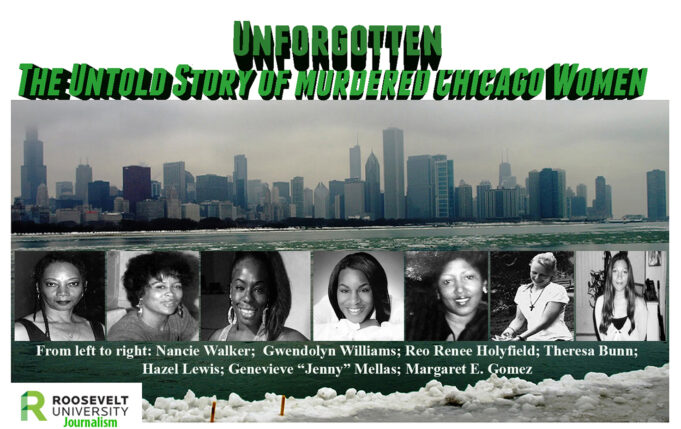

John Fountain, a journalism professor at Roosevelt University, told The Final Call that the effort to protect Black women starts with valuing them. He started the “Unforgotten 51” project to shed light on the names of 51 Black women over two decades who went missing and their cases unsolved. Mr. Fountain and his students researched the images and told the stories of these women which were compiled and placed on a website, Unforgotten51.com, and shared with the media.

“When I look at these women, I see my mother, my cousins, my auntie,” he told The Final Call. “It is difficult for me—and damn near impossible—to see that story and not see that it is important. There isn’t a Black person here alive without a Black woman. Why in the hell can anyone Black not value a Black woman? It is essential to, I think, our survival to respect our women of our culture and race.”

The issue of missing and murdered Black women and girls is not a new phenomenon. The failure of institutions, policies and lawmakers surrounding the disappearance and killing of Black women and girls throughout the country has pained families for decades.

In 2000, the family of Asha Degree, who went missing at age nine, had to battle to keep their daughter in the news while facing “Missing White Woman Syndrome,” media coverage that omits and ignores missing Black and Brown women and plays up White, young, “attractive,” often blonde women who went missing. The term was coined by the late Black female journalist Gwen Ifill.

Twenty-two years later, police still do not know what happened to Asha Degree, according to news reports.

CEO of Peas in Their Pods, Inc.

Gaetane Borders, president and CEO of Peas in Their Pods, Inc., treats the missing children her organization seeks to find as her own. Her mission is to find every Black child reported missing. Her group works with families of missing children by helping to coordinate with police, conducting media outreach, offering counseling, poster distribution and creation and serving as spokespersons for families. They also help organize searches, send alerts to groups they work with around the country, and hold events at schools. The group conducts safety seminars and workshops and offers resources online. Ms. Borders’ group is located in Snellville, Ga.

She argues that the Black community must be vigilant in protecting and finding children, which includes communication, advocacy and individual action, like knowing who lives near you. “Do we have these conversations as a people? Do parents talk to their children about safety? We have to have these conversations in our schools and with each other,” Ms. Borders said.

She further noted that holding law enforcement and lawmakers responsible is critical and not a one-man’s—or woman’s—job.

“We have to understand the situation at large, the seriousness of it. We have to ask them those tough questions, hold them accountable. Why is it that 40 percent of sex trafficked individuals are Black? Ask those tough questions and demand reform. … And don’t just take a response; if they say they’re going to do something, follow-up! And it’s not just one person holding them accountable, it’s a community,” she stressed.

Working for change

In Chicago the demand for answers and proper responses has been made from the halls of Congress—with one congressman calling on the FBI to get involved to another who is part of a congressional caucus devoted to the plight of Black women—to the state legislature to the streets.

Some have begun to respond.

In Cook County, Ill., which includes the city of Chicago, Sheriff Tom Dart responded to the issue of missing Black women and girls by initiating a missing person’s project in 2021, which investigates cases that went unresolved for three or more years. According to his office, the project is investigating 160 cases and asking the public information that will lead to the finding of these women. Forty-three of the missing women are Black, according to the sheriffs department.

Buckner (D-Chicago)

State Representative Kambium Buckner (D-Chicago) created a task force last year and submitted it to Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker’s office for approval. The task force will seek a better understanding of the different factors connected with missing and murdered Black women and seek solutions, he explained. The lawmaker also wants to know why the problem has increased and wants to see action on any solutions the task force advocates backed by the Democratic governor and the Illinois General Assembly.

State Representative Mattie Hunter (D-Chicago) is also awaiting the governor’s approval of her task force on Black women and girls. Her office told The Final Call the task force is expected to be approved this summer. “The goal is for the task force to identify the causes behind this kind of violence, and recommend measures necessary to address and reduce violence against our women and girls,” wrote Halie Owens, state Rep. Hunter’s communications specialist, in an email to The Final Call.

The Final Call contacted the Chicago Police Department for its statistics regarding Black women and girls compared to the total number of missing and murdered females. The department replied via email with the total numbers of Black women reported missing and murdered from 2018-2022 after a Final Call Freedom of Information Act request.

According to police department, over that time period, 268 Black women were killed.

While the data from the department on missing Black women was provided it was unclear how it should be deciphered. But, according to a Chicago Reader 2016 analysis, “Nearly a quarter of the city’s 838 open missing persons cases as of August 1 were Black women between the ages of 11 and 21, according to a Reader analysis of Chicago Police Department data obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request. Advocates say that Black people in general and young Black women in particular are overrepresented in the Chicago data in part because law enforcement and the media are not paying sufficient attention to their cases.”

The Chicago police department told The Final Call it would need more time to gather the comparison data.

Karen Phillips, mother of Kierra Coles, joined other mothers during a news conference in May to raise awareness for missing relatives. Her daughter was 26 years old and three months pregnant when she went missing in 2018. After calling the police department and mayor’s office for two days, she said she only received a phone call back once, after her daughter’s name began to make headlines.

“For you to sign up to be a police officer to protect and serve, y’all should be doing everything y’all can to give families some type of answer instead of ignoring them,” Ms. Phillips said. “There is no value, it’s not their family members so, you know, like they say, it don’t really hit people until it hit home.”

Ms. Phillips also said the Chicago Police Department ignored her calls and demands for answers until she spoke with Mayor Lori Lightfoot. That’s when she received a call from Superintendent David Brown.

“He did give me a call and asked what can they do,” she said. Ms. Phillips said that her daughter’s boyfriend was the last person with her. She said he hasn’t been taken in for questioning yet. Ms. Phillips believes the Chicago Police Department is not doing enough to end the missing Black woman crisis—and her daughter’s case is just one example.

Chicagoan Toni Morris also feels law enforcement is not doing enough to address the cases of missing Black women and girls. She wrote about how disturbing it was on social media. “I started paying attention around late 2018 when the white vans were supposedly abducting women,” she told The Final Call. “I think Black women are being targeted because, unfortunately, they know (the) Chicago Police Department doesn’t care enough to investigate or solve the case.”

Despite contacting the office of Superintendent Brown and the office of Mayor Lightfoot repeatedly via phone calls, emails and on social media for weeks, neither had responded by Final Call press time.

According to the Black and Missing Foundation, located in Hyattsville, Md., the disparity in media coverage is one of the biggest contributors to the lack of urgency in these cases. Their data says that many non-White children are often classified as “runaways” and do not receive the Amber Alert as a missing person would. Amber Alerts, publicized by the news media, electronic billboards and digital signs, spread the word and can result in reports on the local or national news and social media outlets.

The Black and Missing Foundation says the solution is for more diverse hiring in newsrooms—including editors and staff—and who the news outlets present to their audiences.

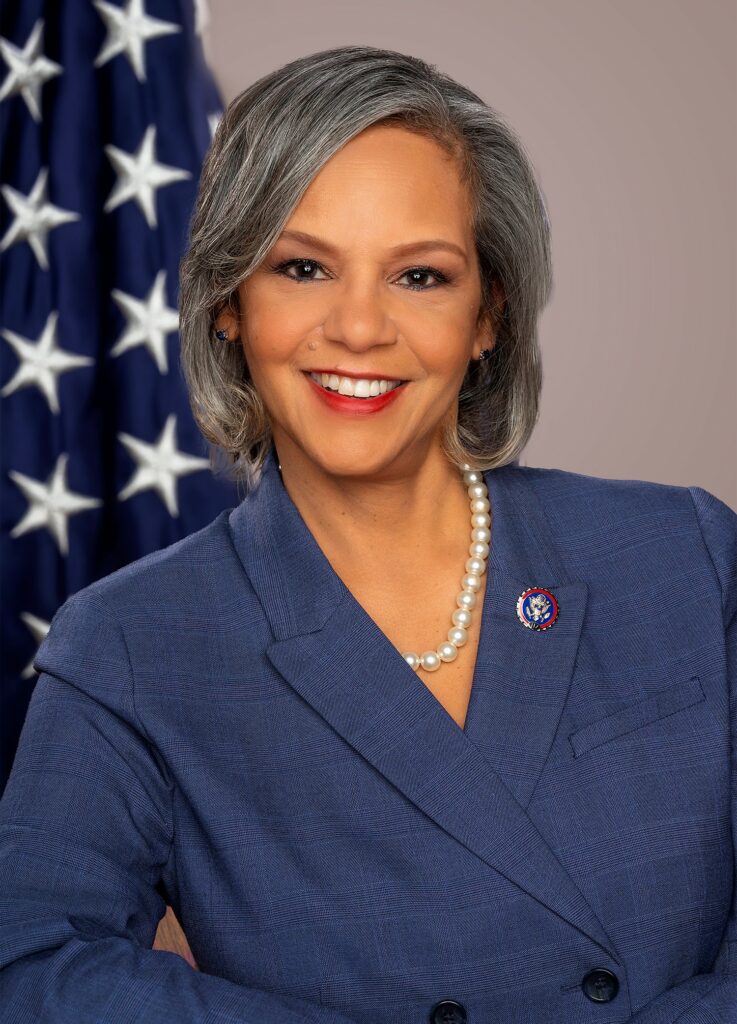

“While Black women account for less than 15 percent of our U.S. population, we made up more than one-third of all missing women reported in 2020,” wrote Rep. Robin Kelly, a Chicago congresswoman who has focused on the crisis, in an opinion piece published in the Chicago Sun Times.

“In addition to making up a disproportionate percentage of all missing people, and receiving less media coverage, Black women and girls are also at increased risk of being harmed. … Black women face a particularly high risk of being killed at the hands of a man. According to the FBI, at least four Black women were murdered per day in 2020. That staggering number is probably an undercount, as crimes against Black women go underreported,” she added. The commentary was published in March.

A member of the Congressional Caucus on Black Women and Girls, Rep. Kelly and her caucus hosted “Not My Girls,” an interactive virtual forum focused on missing Black women and girls from the Chicago area in February. Last year the group issued a report on the status of Black women and girls.

Community responsibility, and outside accountability

“No one can save us from us, but us,” Roosevelt University professor Fountain declared. “I think that we have to be in charge of our (protection). As men, we are supposed to protect our families, protect our women. That’s not macho bravado, that’s godly. That’s spiritual, that’s manly. We know our community. We see things that occur. We can talk to people and get information that might help in solving these cases. We’re a lot closer to the ground than the police are. Getting young men to understand that men of every other race protect their women—let’s protect ours. That’s our job.”

If the responsibility is ours, then the accountability is ours as well.

Cities, states, counties, and the country have millions in tax dollars—Black tax dollars—and those who earn a living on public safety and have a duty to protect the public can’t just be excused. Many activists and advocates believe a balance is needed, but they stress Blacks should not wait for others to take the lead.

Tanisha Williams of the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization said awareness and accountability is key to protecting Black women and girls. The Chicago community organizing group, also known as KOCO, plans to host its 5th annual “We Walk for Her” on June 14 in the heart of the Black community.

“The ‘We Walk for Her’ march was started by a young person who came to KOCO with her concerns about Black women and children going missing at an alarming rate. She was just really concerned about her safety,” Ms. Williams explained.

The march has been a way of keeping the names of women and girls who are missing alive, highlighting a problem, and pushing for politicians to act, she said. She believes lawmakers and law enforcement will have to admit that there is a major problem. “I think if there is acknowledgement, the coalition (can) work on what we want to see, what our demands are,” Ms. Williams added. Some elected officials already support the march and what it stands for, she said.

“We’re hoping that people will walk away with a better understanding of this issue, and that we as a community need to come together,” Ms. Williams said.