Darrell Siggers remembers what it’s like to feel trapped.

“Just imagine being somewhere where you have no control over anything. They can wake you up at four o’clock in the morning and say get up against the wall, strip, take off everything you got on. And they got on riot gear,” he said to The Final Call.

At the age of 20, in 1984 Detroit, he was arrested and convicted of first-degree murder. After years of filing appeals and being denied, in 2017, he contacted a ballistics expert who found that the testimony and evidence in his case was erroneous. With the help of the Wayne County, Mich. Conviction Integrity Unit, his charges were finally dismissed. He was exonerated on October 19, 2018, after serving 34 years for a crime he did not commit. He described it as “34 years of hell in a cell.”

Contributing factors in his case included perjury or false accusation and official misconduct, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

The registry released its annual report April 12 detailing exonerations in 2021. It recorded 161 exonerations last year. “Exonerees lost an average of 11.5 years to wrongful imprisonment for crimes they did not commit—1,849 years in total,” the report states. The most frequent contributing factor in the recorded cases was perjury or other false accusations, followed by official misconduct.

Barbara O’Brien, the editor of the National Registry of Exonerations and a professor at Michigan State University College of Law, told The Final Call that perjury and false accusation is generally the most frequent factor as it can occur in any type of case.

“And it could be somebody who is making up the charge completely for a crime that never happened. It could be somebody who is lying about something the defendant said because they want to get a better deal in their own case. It could be a police officer who testified falsely at the trial or in a preliminary hearing,” she said.

Official misconduct is any time a government official who works for the state—a police officer, a prosecutor, a forensic analyst—commits some wrong that contributes to the false conviction, Ms. O’Brien explained. The most common form is the concealing of exculpatory evidence.

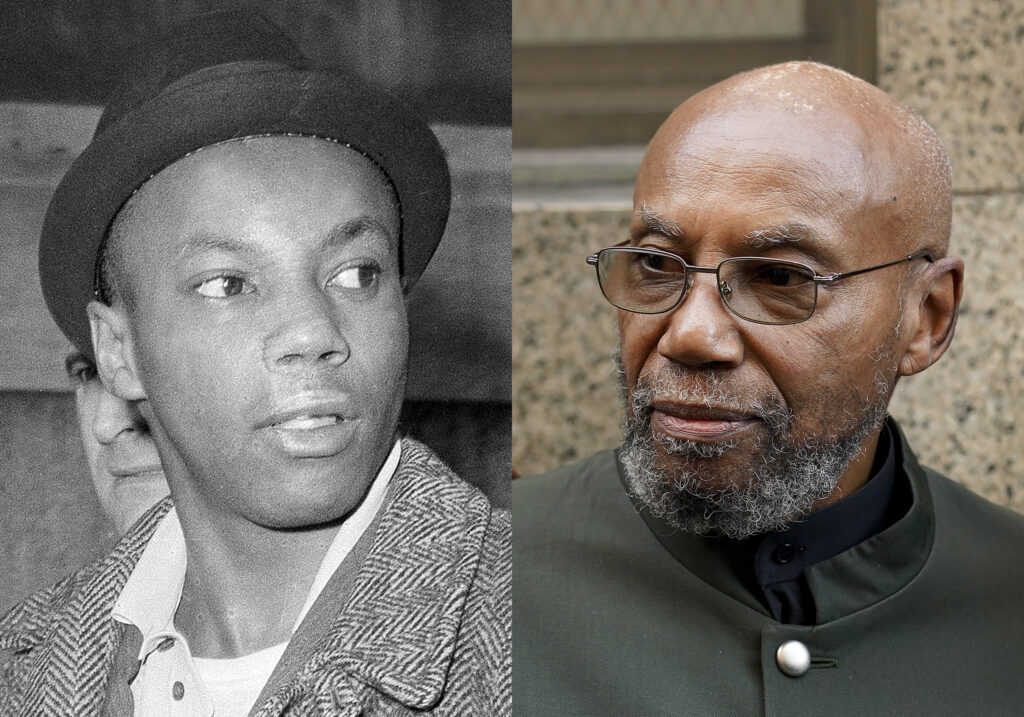

2021 exonerees included Khalil Islam and Muhammad Aziz, who were falsely convicted for the 1965 murder of Malcolm X.

“I do not need this court, these prosecutors or a piece of paper to tell me I am innocent. … I am an 83-year-old who was victimized by the criminal justice system,” Muhammad Aziz said in a statement.

Racial disparities

The National Registry of Exonerations has recorded over 3,000 exonerations since 1989. Illinois had the most exonerations in 2021, 38, followed by New York with 18 and California and Michigan with 11.

“We don’t know who’s number one in false convictions. We only know who’s number one in exonerations. The last several years, Illinois has had an extremely high number of exonerations because there has been a slew of exonerations all related to the misconduct of one particular police officer and his colleagues,” Ms. O’Brien said.

Fourteen of the Illinois cases can be linked to corrupt police officers who operated under former Chicago Police Sergeant Ronald Watts. He and his team planted drugs on Black people, most of whom lived in public housing, for their refusal to pay bribes. He was federally indicted and served less than two years in prison. Fifteen of the cases in Illinois were based on wrongful convictions for weapons possession.

“There’s a ton of cases from this one bad actor and others around him that inflate the numbers in Illinois,” Ms. O’Brien said. But, she said, there could be other bad actors in other states who are committing misconduct and haven’t been caught, yet.

Lionel Muhammad also linked exoneration cases in Illinois to Jon Burge, an ex-commander in the Chicago Police Department who was accused of torturing innocent Black people into confessing.

“I know that all of these officers that are doing this came up under Jon Burge, or they were an extension of Jon Burge and his torture tactics with putting cases on brothers and sisters,” he said to The Final Call. “I know that much. So, you find officers that do the same thing, but where does the mind come from? That’s where it came from, Jon Burge putting drugs on people, sending them to prison for drugs.”

Mr. Muhammad is the Nation of Islam’s Central Regional Prison Reform Student Minister and the assistant to the Nation’s Student National Prison Reform Minister Abdullah Muhammad. He did over 23 years in prison for a crime he did not commit.

About 67 percent of exonerees in 2021 were Black, and 24 percent were White.

Ms. O’Brien described that in the cases linked to former Sgt. Watts, many of the victims filed complaints about what was happening, but no one believed them.

“These defendants who were wrongly convicted were preyed upon because of their vulnerability, because they could be extorted and nobody would believe them. And so they were really easy targets,” she said.

She explained a subtler form of discrimination that could be at play: the lack of diversity on a jury. She pointed to the case of Curtis Flowers, a Black man out of Mississippi who was tried for murder six times, with four resulting in convictions. In one of the trials, the prosecutor would not allow Black people on the jury. Another resulted in a hung jury, as the only Black man on the jury did not think the evidence was compelling enough to convict. The juror was then charged with perjury.

“The charges were eventually thrown out, but the message was clear. Basically, they’re taking a juror who voted to acquit out of the courtroom in handcuffs. That sends a very clear message as to whose voices they respect and whose will be punished for saying the wrong thing,” Ms. O’Brien said.

In cases with mistaken witness identification, she explained that it’s always a problem, but it’s worse when a White person is identifying people of another race.

For Mr. Muhammad, Black people are convicted for two reasons: having no money and no voice.

“When you don’t have a voice, you wind up going to prison. You wind up going to jail, because the only voice that you really have is mama, aunty. Nobody else is even concerned. The community really doesn’t care until it happens to them,” he said.

Darrell Siggers tied the racial disparities present in wrongful convictions to slavery and the Jim Crow era. He noted that some Caucasian police, prosecutors and judges have intrinsic bias, meaning “they can’t see a brother in me. They can’t see an uncle in me. They can’t see a nephew in me. They can’t see a father or a son in me. They see Black people as the enemy.”

“If you can’t see yourself in me on some level, then it is easier for you as a prosecutor, judge, lawyer, policeman, it is easy for you to treat me differently,” he said.

Adjusting to life outside

When Mr. Siggers was exonerated, he had to relearn life. While imprisoned, he had lost his mother and father. Many of his older family members were gone. He lost his oldest daughter a month after he returned home.

“It has affected me in ways that I don’t even know if words can fully explain,” he said. Though he was able to maintain a sense of mental, psychological and emotional balance, he explained that many people who get out don’t have the wherewithal to cope with life on the outside.

“Because in prison, you don’t make decisions. All your decisions are made for you. When you eat, when you sleep, when you get up. All that stuff, those decisions are made for you, so when you get out here, life comes at you 100 miles an hour,” he said.

He described that many people suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, and what he likes to refer to as post-traumatic prison disorder. Like others, he has been to counseling to help make the struggle easier.

Since being out, he has written a book titled, “What you need to know before hiring a lawyer and what you need to know before filing an appeal,” and he founded legalaccessplus.com, an online database that profiles wrongful convictions of prisoners.

During his Million Man March address delivered on Oct. 16, 1995, on The National Mall, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam told the sea of almost two million Black men to adopt an inmate.

“How many of you will adopt one Black man in prison and make him your pal, your brother for life?” he questioned. “Help him through the incarceration. Well, go to the chaplain of that jail and say you want to adopt one inmate to start writing to that person, visiting that person, helping that person. And since so many of us have been there already, we know what they suffer. Let’s help our brothers and sisters who are locked down.”

“Why did the Minister give us those instructions? Because the Minister said to me personally … he said because that’s a whole ‘nother world, brother,” Lionel Muhammad recounted. “You got 2.6 million people locked up. He said if we’re disconnected from that world, we can never change the reality of this world. He said but once you become connected to those brothers and sisters that’s locked up, then you connect them back to the world and then you can change the reality of the world in which we live.”

Mr. Muhammad explained the importance of family and community. In his prison reform work, he helps connect formerly incarcerated people back to their communities.

“Because if they’re not connected to the community when they come home, they don’t have nothing to come home to. It’s hard to get a job. Don’t nobody know you. You don’t have any friends. You don’t have any associates,” he said.

He said the community should be involved in the development and rehabilitation of those incarcerated.

When it comes to wrongful convictions, immunity laws often protect prosecutors and police officers.

“Prosecutors have absolute immunity from lawsuits. Police officers have qualified immunity,” which, in theory, makes sense, Ms. O’Brien said.

The problem arises when an officer engages in egregious misconduct.

“The court will say you can’t sue them. So, there’s a lot of things about our system that shield actors, bad actors, from consequences of their actions,” Ms. O’Brien stated.

Mr. Muhammad said the community is responsible for the lack of accountability when people are wrongfully convicted.

“We keep putting the same people that are responsible for destroying our families back in office, and we don’t do any research to find out who these people are and who we’re voting for,” he said.

Mr. Siggers described how in a lot of cases, including his, by the time exonerees are let out, the police who were involved are dead, and the only thing that can be done is to file a lawsuit.

Preventing wrongful convictions

Those with the National Registry of Exonerations have been seeing more exonerations over time. Ms. O’Brien attributed the increase to more conviction integrity units being formed in prosecutors’ offices and to innocence organizations. The units are dedicated to revisiting older cases where there’s plausible claims of innocence, she said. But even so, there are still way more defendants who are asking for review of their cases than there are the mechanisms to do so, she noted.

Mr. Siggers pointed out that before conviction integrity units, there was no real method to exonerate someone, as courts are not constitutionally designed to investigate cases or determine actual innocence.

“It has to be based on some type of underlying constitutional violation, whether it be police misconduct, prosecutorial misconduct, ineffective assistance of counsel. You have to attach one of those claims to claim innocence even to bring it forward,” he said.

He recommended several solutions to help prevent wrongful convictions. For cases of mistaken identification, he suggested having lineups of an array of people with similar characteristics, so that the lineup is not unfairly suggestive. He also stated that attorneys should be present and that the lineup should be videotaped.

For convictions based on ineffective assistance of counsel, he suggested financial resources be provided for defendants and court-appointed lawyers to be able to hire a forensic expert, a private investigator and a second lawyer.

One last solution he recommended was for there to be certain levels to ensure that appointed lawyers are competent and qualified and to ensure that lawyers are not taking first-degree murder and capital cases as their first, second or third cases.

Mr. Muhammad said the whole system has to be changed.

“Telling people not to do wrong is like talking to the brick wall,” he said.