By Barrington M. Salmon and Naba’a Muhammad

In East St. Louis, Ill., while others were celebrating America’s Independence Day, activist Matt Hawkins marched on city hall to bring attention to Black residents killed during a 1917 race massacre. He and others are calling for reparations for the descendants of those murdered by White mobs.

“Nobody’s trying to get anything extra. I believe reparations are about healing,” Mr. Hawkins said in a media interview. “I’m not angry. I’m just saying, my God, how can we do this? We want peace. We want partnership. We just don’t have the money.”

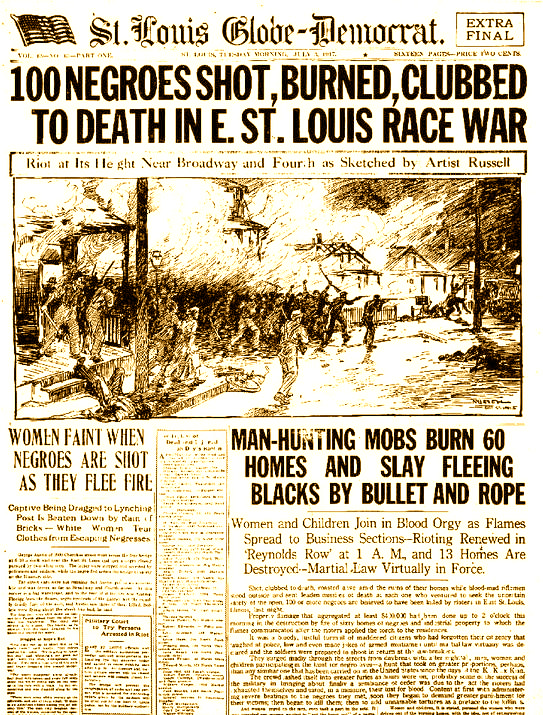

Commonly known as the East St. Louis race riots, the attacks on Black people in May and July 1917 were carried out by White mobs upset about companies using Black workers as strikebreakers. At the time, East St. Louis was mostly White, but Blacks had lived in the city for decades. According to the official count, 39 Blacks and eight Whites were killed in the July 2 attacks. The NAACP estimated the number of deaths of Black people to be anywhere from 100 to 200; the day following the attack, the Belleville News-Democrat reported “at least 100” Black people had died.

By destroying Black homes and businesses, the White mobs did hundreds of thousands of dollars in property damage, say people like J.D. Dixon.

“That’s generational wealth lost,” said Mr. Dixon, one of the organizers of the inaugural rally for reparations, a founder of Empire 13 and former write-in candidate for mayor of Belleville.

Mr. Dixon, Mr. Hawkins and other advocates and activists point out that those Black family homes, businesses and wealth couldn’t be passed down to the next generation. Survivors had to start over, including the considerable number of people who were forced to flee across the Mississippi River to St. Louis.

Mr. Dixon is working to gain more signatories on a petition calling for a “complete system of reparations” in East St. Louis, that he plans to send on to U.S. Sens. Tammy Duckworth and Dick Durbin and Gov. J.B. Pritzker.

Cities and emerging reparations efforts

A number of U.S. cities have planned or are already offering reparations of one type or another to Black residents. Evanston, Ill., was the first, and since then, municipalities like Amherst, Mass., Asheville, N.C., Chicago, and Providence, Rhode Island, along with the Virginia Theological Seminary, the University of Virginia, Rutgers, Princeton, Harvard and other institutions of higher learning have followed suit.

Little by little, those running universities and colleges, titans of business and commerce, lawmakers, policymakers and others are acknowledging the need to make amends for decades and centuries of America exploiting free labor stolen from enslaved Africans; conceding the deep and lasting damage done by the racism deeply embedded in every aspect of American society; and the enduring injury caused by perpetuating the falsehood of White supremacy and Black inferiority.

Reparations efforts go back to the 1800s and earlier for Blacks to obtain some restitution and some justice for their suffering. Some have argued reparations must include land and Black self-determination. The Honorable Elijah Muhammad, patriarch of the Nation of Islam, taught a different solution type of reparations which includes a separate state or territory for Blacks and support in that state for 20-25 years as they become fully self-sufficient. He called it a divine solution and the best solution to the problem of Black and White. There can be no peaceful co-existence, he said.

“We want our people in America whose parents or grandparents were descendants from slaves, to be allowed to establish a separate state or territory of their own—either on this continent or elsewhere. We believe that our former slave masters are obligated to provide such land and that the area must be fertile and minerally rich. We believe that our former slave masters are obligated to maintain and supply our needs in this separate territory for the next 20 to 25 years—until we are able to produce and supply our own needs,” the Honorable Elijah Muhammad stated.

The discussion of what was once a ridiculed and “radical” topic has continued over the past couple years and wider acceptance of reparations has taken a long time with tireless warriors like ancestors Callie House, Queen Mother Moore, Dr. Conrad Worrill, Congressman John Conyers, and ongoing fighters like Nkechi Taifa, Dr. Ron Daniels, Kamm Howard, Tariq Nasheed and Yvette Carnell.

Mr. Howard, elected to his third term as national co-chairman of National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, N’COBRA, in June, had a measured response to the flurry of activity and reparations progress.

“I am cautiously optimistic. This is America and this is part of the struggle,” said Mr. Howard, who has been a leader in the reparations movement for 16 years.

“With Evanston initially breaking ground, after that, city-after-city has begun to see disparities in cities,” he noted.

Mr. Howard said city officials, university brass, city, county and state officials and others in a position to effect and direct change understand the deleterious effects of Jim Crow, highways built through thriving Black communities, mass incarceration, predatory lending, redlining, the theft of generational wealth and other racially related actions by those in power.

And activists and leaders are working to redress those generations-long grievances.

Evanston Alderman Robin Rue Simmons developed a reparations plan that was presented to the Evanston city council on March 22. The body voted 8-1 to disburse $400,000 to former Black homeowners to address their housing needs. The city is prepared to give $25,000 grants and mortgage assistance to eligible Black residents who have experienced discrimination or who can show that they are direct descendants of people who lived in Evanston between 1919 and 1969.

Ms. Rue Simmons said the lawmakers’ action was in response to a long history of discriminatory housing practices, programs and policies in the city and the checkered history of the way Black Evanston residents have been treated.

“This is not full repair but the first step towards repair and funding for damages done to Black residents because of housing policies that discriminated against them,” she said. “We have a racial wealth divide that is consistent. There were ceremonial efforts and the promise of commitment. I realized that we were being made a mockery of. There were initiatives with no money, action plan or a move towards empowerment.”

“I wanted us to be financially well and not dependent on others,” she said.

There has been pushback from several quarters, including those who believe these measures don’t really fall into the category of reparations.

Some say the amount being offered is too small and there are forces unalterably opposed to giving any type of compensation to the descendants of enslaved Africans.

Those in the movement, however, are undeterred.

“There have been lawsuits, cries of reverse discrimination and pushback. For example, the repair for Black farmers has been contested. There will be backlash, pushback and challenges but that doesn’t stop us from planning, pushing our plan and moving forward,” Mr. Howard said.

Washington, D.C. attorney and activist Nkechi Taifa is clear on what reparations must look like.

“It includes restitution and in the specific context of Black people, a formal acknowledgement of historical wrong; official, unfettered apologies; recognition of injuries and policies and practices in education and culture which continues today,” she said.

“There must be commitment from corporations, industry and state government, actual compensation in whatever form or forms agreed upon,” she asserted. “This must come from people, not those on high. Legislation is not litigation. Legislation has been struck down. It’s not just economic. There are so many injury areas. The remedy must be multifaceted as well.”

Dr. Sandy Darity, a reparations scholar and economist, has called for “a proposal that ensures that the reparations plan is intended for Black Americans who are descendants of persons enslaved in the United States. Secondly, the proposal should establish that a primary objective of the plan is to eliminate racial wealth differences in the United States.

And this would require a minimal expenditure of $10 to $12 trillion. And then third, the commission’s proposal must be designed in such a way that it sets, as a priority, the provision of the reparations payments in direct fashion to eligible recipients. And again, the eligible recipients should be Black Americans who are the descendants of persons who were denied the 40-acre land grants as restitution in the aftermath of the Civil War.”

A continuing struggle

Social media influencer Ericka Quinichette told The Final Call she believes reparations should happen and people should continue to fight for it—even if it doesn’t happen in their lifetimes.

“Those seeking reparations shouldn’t think it won’t happen,” she said. At one point LGBTQIA rights and accommodations for people with disabilities looked like pipe dreams, but their advocates kept fighting and pushing, Ms. Quinichette noted. “Now no one thinks it’s an issue,” she observed.

The Missouri resident and mother supports “the idea of lump sum disbursements at best and at a minimum there should be free college education.”

Ms. Quinichette cited the examples of places in Canada that give residents in certain oil-producing areas $2,500 checks per month.

“I think there are ways to do that,” she said. “Back in the day, (Harvard law professor) Charles Ogletree was going for corporations, insurance companies and universities with direct ties to slavery. He was fighting for them to pay.”

Now, Ms. Quinichette said, increasingly significant segments of society have embraced Prof. Ogletree’s approach to recompense, repair and reconciliation for institutions’ deep involvement in America’s slave past.

The Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria, Va., has sought to make amends to the descendants of enslaved Africans it used for more than a century, during slavery, Reconstruction and beyond. Between 1823 and 1951, hundreds of Black people were forced to work for little or no pay on the campus as farmers, dishwashers and cooks, among other jobs.

Back then faculty members and students also brought their own enslaved people, said Ebonee Davis, an associate for programming and historical research at the seminary. In 2019 the school announced it had set aside $1.7 million to pay reparations to the descendants of slaves who worked on its campus. Earlier this year it followed through on its promise and began disbursing yearly payments of $2,100 to each direct descendant of Blacks who worked there.

Fifteen people have received payments so far, and the seminary is expecting to compensate more descendants as they are identified. Some scholars of reparations say the seminary is the first such program in the country.

The seminary started cutting checks for the descendants—whom it calls “shareholders”—in February. The expectation is that the $1.7 million endowment will continue to grow and fund future payments.

The endowment acknowledges the seminary’s past participation in oppression and comes as the school prepares to celebrate its bicentennial in 2023.

Federal legislation and the need for land

Mr. Howard said a congressional hearing on H.R. 40, federal legislation that would study reparations and how it would be implemented, chaired by Rep. Sheila Jackson-Lee (D-Texas) earlier this year was tremendously important. It focused on developing and implementing proposals designed to repair, compensate and heal Black people in this country, Mr. Howard said. And, he said he and other advocates and activists continue pushing for the Biden administration and lawmakers to throw their full support behind the bill and its passage.

“We’re holding him to his word twice,” said Mr. Howard of the president. “He said he has our back and we will hold him to those promises. We don’t want a Clinton-type study commission. We hope to get the House vote before September and use that to leverage an executive order from the president.”

While H.R. 40 has widespread support with 194 sponsors in the House, Mr. Howard said there will not be 60 members in the U.S. Senate who’ll support the companion bill, despite support from Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

“We have 194 sponsors in the House but we need 218,” Mr. Howard explained. “So we’re whipping the final 20 votes. Reps. Clyburn and Hoyer and House Speaker Pelosi say they will introduce it on the floor, but we have to do this before the end of this session.”

A summer 2020 Gallup poll revealed Blacks are becoming increasingly dissatisfied. The poll found 21 percent of Black adults in the U.S. are satisfied with the way Black people have been treated. Seventy-nine percent are dissatisfied.

The Honorable Elijah Muhammad wrote in The Muslim Program, “Since we cannot get along with them in peace and equality, after giving them 400 years of our sweat and blood and receiving in return some of the worst treatment human beings have ever experienced, we believe our contributions to this land and the suffering forced upon us by White America, justifies our demand for complete separation in a state or territory of our own.”

His words on separation are published on the back page of every edition of The Final Call newspaper, under Point No. 4 of “What the Muslims Want.”

“Now, I’m asking you to reason with the Honorable Elijah Muhammad; I want us to look at what Elijah Muhammad put on the back page of our newspaper, The Final Call,” Minister Louis Farrakhan said in his address “Separation or Death” at the 22nd anniversary of the 1995 Million Man March.

“So I want to say to the government: We are not just somebody that’s desirous of separating from you on our own. The Program of ‘separation’ is given by God, and backed by God as the only solution to the toxic relationship between Black and White,” the Minister said.

Dr. Ava Muhammad, the National Spokesperson for Minister Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam, told The Final Call via email that the essential master-slave relationship between Black and White has never changed.

“The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan has taught us, ‘As long as we live with White people, we will live under White people,’ ” she continued.

In June 2018, Dr. Ava Muhammad embarked on a series of town hall meetings in response to Minister Farrakhan’s expressed desire for meetings and discussions around the country on separation. She visited 21 cities before the Covid-19 pandemic prevented physical gatherings.

Black people are not only ready to separate, but that they are anxious to get away from their tormentors and be free and independent, she argued.

As the Honorable Elijah Muhammad sets forth in Point No. 9 of “What the Muslims Believe:” “WE BELIEVE that the offer of integration is hypocritical and is made by those who are trying to deceive the black peoples into believing that their 400-year-old open enemies of freedom, justice and equality are, all of a sudden, their ‘friends.’ Furthermore, we believe that such deception is intended to prevent black people from realizing that the time in history has arrived for the separation from the whites of this nation.”

It continues: “If the white people are truthful about their professed friendship toward the so-called Negro, they can prove it by dividing up America with their slaves. We do not believe that America will ever be able to furnish enough jobs for her own millions of unemployed, in addition to jobs for the 20,000,000 black people as well.”

Dr. Muhammad also quoted Point No. 5 of “What the Muslims Want,” which says: “We want every black man and woman to have the freedom to accept or reject being separated from the slave master’s children and establish a land of their own.”

(The Associated Press and Final Call staff contributed to this story.)