Copyright is the most important type of protection available to musicians.

It has even been boldly asserted that “the recording industry is built on copyrights.”

Without copyright, wrote Stellenbosch University professor Owen Henry Dean in a 2015 study, “there is very little protection available to musicians and producers.”

Taking music without compensating the original creator is at the heart of a fight by South African musicians led in part by South African singer Tebogo Sithathu. His group, The Twins, was once managed by Nelson Mandela’s late daughter Zindzi Mandela. The singer recently resigned as spokesperson for the South African Music Industry Council.

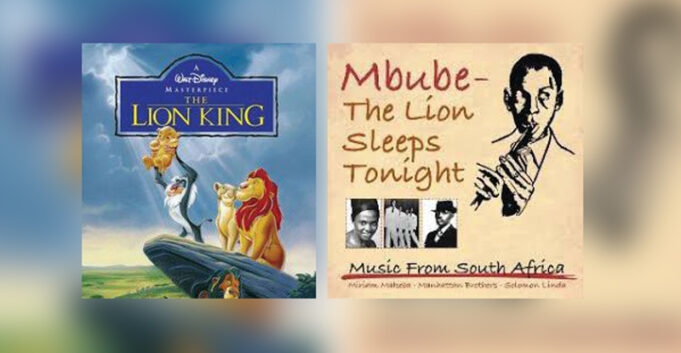

According to Sithathu and Andrew Rens, who has a Ph.D. in copyright law, a case study involves the misappropriation of Solomon Linda’s (1909-1962) original song, “Mbube,” that later became the Disney produced Lion King hit song “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.”

Both Sithathu and attorney Rens, from Johannesburg and Cape Town respectfully, during separate interviews spoke with Africa Watch. “I went to university just to use what happened to him (Linda) as a kind of case study as to how musicians have historically been screwed. I went to introduction of intellectual properties (at) Stellenbosch University just to build my case on that. I did that as a case study, ‘the Solomon Linda story.’ I actually saw the deed of assignment that he signed,” Sithathu said via WhatsApp.

The deed of assignment that Solomon signed says he was paid ten shillings, the equivalent of ten cents.

To add insult to injury, even though Linda’s three daughters, after a long legal battle, received royalties and recognition for their father’s song, during his lifetime Linda’s notoriety never extended beyond South Africa.

Nor did he receive compensation that would have helped relieve he and his family’s “destitute” situation. He died with less than $25 in his bank account.

A settlement was eventually reached, according to Al Jazeera, with New Jersey-based Abilene Music, which holds the copyright to “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” and in turn licensed it to the Walt Disney Corporation. The $1.6 million settlement included back royalties and future royalties on “a worldwide basis.”

The song has been recorded by more than 150 artists, featured in over 15 movies and stage productions as well as translated into several languages including French, Japanese, Danish and Spanish.

Much has been written concerning “Mbube,” which means lion, including the fact that its misappropriation by the U.S. corporate run music and entertainment industry would give insight, to this very day, about several important musical and ethical questions.

This includes who really owns a musician’s genius and to what degree a musician’s intellectual property or musical genius must a musical work be transformed, as a hip hop artist told this author, “grafted from original,” until it can be considered a new original, and who deserves compensation or royalties?

Both Sithathu and Rens said that because of the coronavirus pandemic South African musicians are struggling to survive, unable to perform because of “lockdown,” and not receiving royalties around the world for their music.

Sithathu said this stems from the unwillingness of South African president Cyril Ramaphosa to sign a copyright bill passed by Parliament that has sat on his desk for 14 months.

“I was very involved in the lobbying group pressuring Ramaphosa to sign. So what I can tell you is the pressure from the U.S., from big business, big recording companies, (including) Universal and Sony Music … put pressure on Ramaphosa not to sign the bill. The U.S. threatened him with the trade embargo and all those kinds of crap obviously. And we were in difficult times. The economy was not growing and I think the president just caved in,” said Sithathu.

Rens said Parliament passed the bill in March of 2019, “and it just sat on his (Ramaphosa’s) desk.”

“It’s unusual because this particular president has been pretty active. He’s been trying to move things along. Certain things that stalled under his predecessor he’s been, ‘Let’s make them happen.’ So what we know is there was obviously some kind of communication from the United States, its trade representative and the European Commission, even before it was passed. As soon as it was passed to the president’s office and then the United States initiated this (trade) hearing process,” he said.

The president’s decision not to sign the bill highlights the influence and power of the music and entertainment industry. According to Laura Kayali, in a piece written on politico.eu, the industry opposed the reformed copyright bill “for fear it would set a standard for the rest of the African continent.”

It also shows hesitation on the part of the South African president for fear of damaging trade relations with the U.S. and loss of up to $2 billion in export revenues.

In December of 2019, a piece titled “Making Sense of South Africa’s New Copyright Bill And US Trade Threats” predicted that “behind the scenes at a upcoming January 30, 2020 generalized System of Preferences benefits review hearing, the U.S. trade rep will more than likely complain or ‘bully’ ” South Africa.

“The primary complaint about the bill involves its fair use clause—which is modeled on U.S. law. That and rights to use excerpts in education, which exist in nearly every developing country. The complaints also involve the proposed extensions of protections for local creators. This includes rights to royalties, limitations on unfair contracts, and reversion of all copyright assignments to creators after 25 years.”

Concerning his resignation from the South African Music Industry Council, Sithathu said he quit because the group had “problems with my position on the copyright bill.” Sithathu aka DISRUPTOR T, in the music industry, is one of South Africa’s most outspoken artists. He said the council was being influenced by “major record companies and was under the umbrella of the recording industry of South Africa, where you find Universal Music and Sony.” “All of these guys are the proxies of the American multinational (corporations) that did not want Ramaphosa to sign the bill,” he said.

Rens argued the dire circumstances South Africa’s musicians find themselves in, as the result of the coronavirus pandemic, could have been eased by Ramaphosa’s signing of the bill.

“This act that could of been in place in March that said you always get royalties, no matter what deal you sign. No matter what you’ve signed with (a) record company you get a minimum royalty as long as the work is profitable. It’s their creative work … earning money that they are not seeing any part of it.”

Follow @jehronmuhammad on Twitter.