In words, there is universal acceptance that the rights of women and children must be respected and protected. In practice, however, their rights are often undermined and ignored.

For Black women and children in the United States, abuse and disregarded rights are especially in play while in the hands of law enforcement, says a recent report that concluded U.S. law enforcement personnel constantly commit human rights violations against Black people.

The report by the International Commission of Inquiry on the Systemic Racism and Police Violence Against Blacks that in the United States amassed evidence of systemic racist violence against U.S. Blacks constitutes a violation of human rights and fundamental freedoms.

“That is violence visited upon women, children, people who are old, people who are suffering with mental illnesses, and the only thing in common is the color of their skin,” said Lennox Hines, human rights attorney, and coordinator of the commission.

The wide-ranging report released April 27 at a press conference via Zoom, points out that Black women and children are not spared from extrajudicial killings and injury by police. It revealed they are disproportionately represented, targeted, and victimized by systemic racist police violence and impunity.

Black women are 1.4 times more likely to die in this manner than White females. The report also stated that the war on drugs is a significant driver of police violence against Black women and girls. Numerous studies have concluded that Black women are excessively subjected to traffic stops, a law enforcement tactic popularly called racial profiling.

This use of force against unarmed Blacks ending in fatalities often occurred during traffic or investigatory stops. The commissioners found that people were targeted on the basis of their race. There are documented examples of the disparity of how Black and Brown people are handled and Whites are handled by law enforcement.

Black women are brutalized and killed at a higher rate than White women in violation of both U.S. and international law with respect to the use of force.

One example is the 2015 pretextual traffic stop and subsequent arrest of Sandra Bland, a Black 28-year-old woman, later found hanged in a jail cell near Houston Texas. Dash Cam video showed a hostile officer escalating the encounter in their exchange between the two. It was supposed to be a random traffic stop but the young woman ended up dead in a jail cell.

“We’ve seen cases where in traffic stops when Whites who are stopped don’t risk losing their lives,” said Atty. Hines.

Black women also lose their lives when cops are called on mental health and domestic situations. Among incidents found in the report:

Shereese Francis, 29, was suffocated by N.Y. police officers in 2012. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia and one month before being killed had stopped taking her medication because of side effects. This was not new, most times Ms. Francis’ mother would call an ambulance to transport her to the hospital for treatment.

However, her sister dialed non-emergency 311, that redirected to 911 emergency, and summoned police instead.

Ms. Francis died from asphyxia after cops attempted to handcuff her. Four cops held her face down into a mattress while kneeling on her back, obstructing her breathing. The officers were not disciplined nor criminally charged for her death.

Ma’Khia Bryant, the 16-year-old foster child who was shot and killed by a Columbus, Ohio, police officer last month was a victim of a multilayered problem of a flawed system and misperception about the role of cops.

“Ma’Khia was a beloved Black girl who would still be here if we didn’t perseverate on the myth that cops and policing keep us safe. If we focused on how Black girls are perceived and policed from the youngest age in every institution.” tweeted Erika K. Wilson, an attorney and law professor in North Carolina.

Ms. Wilson’s April 29 tweet speaks to the most vulnerable targets who are sidelined and devalued, then further victimized by systemic failure. She wrote, what is not adequately understood is that for Black women, girls, and gender-nonconforming people, a call for help is all too often fatal.

“If we understood the violence Black girls routinely experience in the foster system as part of the violence we are fighting to end,” she said.

In other circumstances cops “put down” young Blacks like slaughtering animals, while comparatively Whites were taken into custody with courtesy, even after committing the most egregious of acts.

In October 2020, Vincent Truitt, 17, a passenger in an alleged stolen vehicle was shot twice in his back by Cobb County, Ga., police, seconds after exiting the vehicle. Following a brief car chase, the police used a PIT maneuver behind the car causing the vehicle to stop. The driver exited and fled; Vincent exited seconds later and was shot.

During the commission hearings, Truitt family attorneys testified that prior to being shot, Vincent posed no threat to the police. Afterward questions of transparency and “unholy relationships” between police and prosecutors came into question.

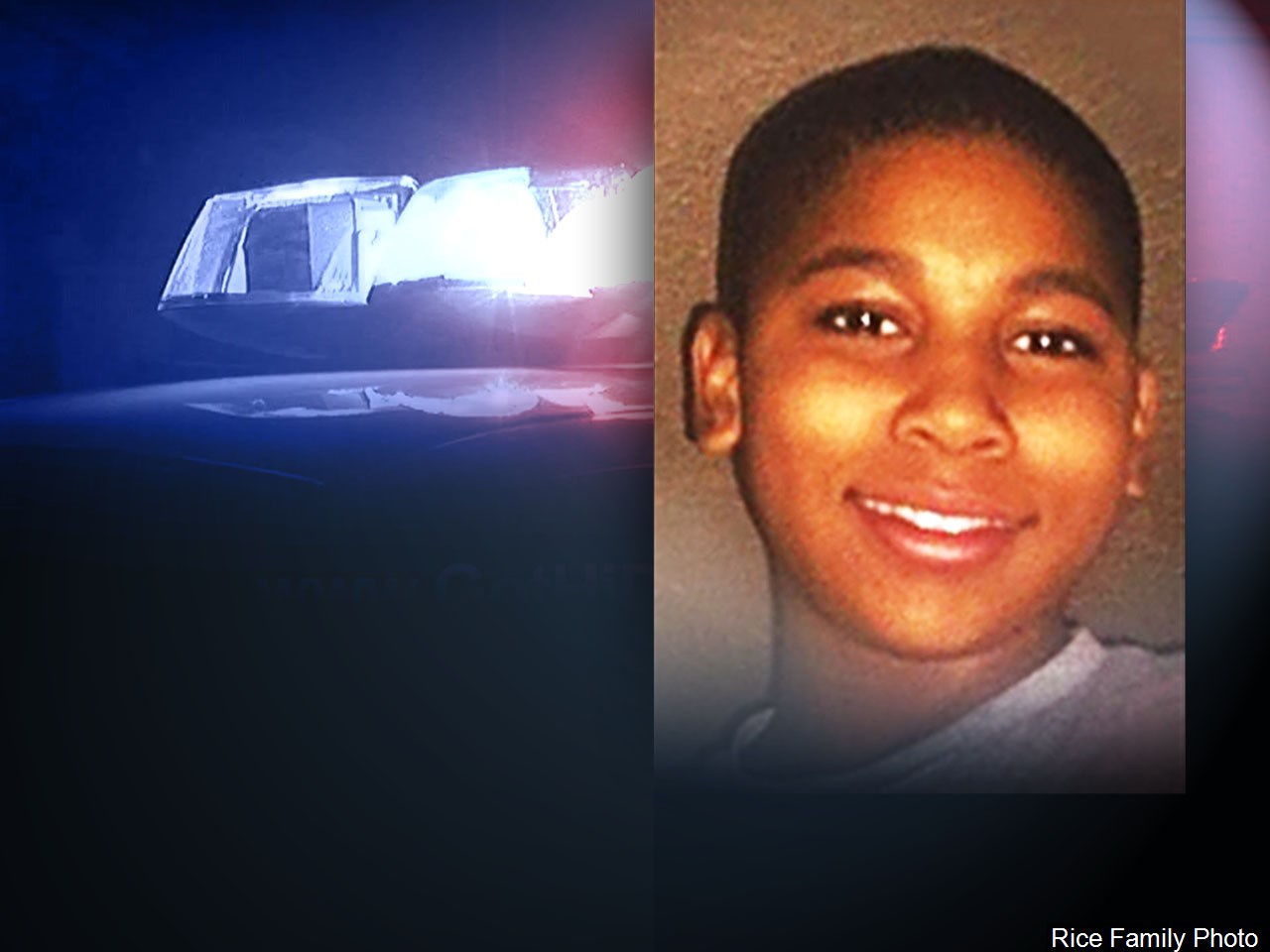

Vincent Truitt was treated vastly different from the August 2020 case of Kyle Rittenhouse, a 17-year-old White male who killed two people, after firing his AR-15 into a crowd of Black Lives Matter protestors in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Cops calmly arrested Mr. Rittenhouse who left the scene and turned himself in, unlike 12-year-old Tamir Rice, who was killed without warning in 2014 while playing in a park with a toy gun.

Although video footage shows the entire incident happened within two seconds, one officer claimed he ordered Tamir to put his hands up three times and shot Tamir out of fear for his life.

During commission hearings, Samaria Rice, Tamir’s mother, and Rice family attorney Billy Mills said the U.S. justice system failed on every level. From a grand jury to the Department of Justice, there were no criminal charges against the officers involved. The Justice Dept. claimed the footage of Tamir’s shooting was too poor in quality to conclusively determine what had happened.

Considering the reoccurrence of cops killing Blacks, the questions loom, would the officers have approached differently if Tamir was a White child?

Would the county prosecutor and federal prosecution have gone forward, if Tamir was a White child?

“We appreciate the opportunity to present this case to the United Nations … because it appears that the avenues that ought to be left to us within the United States… have been stymied every step of the way,” said Mr. Mills.

“There’s no doubt about it that race plays a dominant factor in how the police treat and react to Black citizens,” Atty Hines told The Final Call.

Rights advocates see a contradiction that America has yet to address as calls grow louder for America to answer for what they argue is systemic criminalization of Black life.

International treaties have been established to address the mistreatment and safeguard the human rights of women and children. However, the U.S. has not ratified UN Conventions on women and children. These manifestos and points of international law clearly spells out the rights of children in criminal cases.

“No child shall be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment … . The arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall … be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time,” they say.

Because of far reaching effects of systemic racism on Black women and children, the U.S. is not complying with the Convention on Children.

An NAACP Criminal Justice Fact Sheet said, nationwide, Black children represent 32 percent of children arrested, 42 percent of detained children, and 52 percent whose cases are judicially waived to criminal court.

The U.S. criminal justice system is heavily impacted by the bias of police mentality, as well as outdated judicial precedents, said the NAACP. It is largely driven by racial disparities, which directly obstruct and deconstruct Black communities. Overall Blacks are incarcerated more than five times the rate of Whites with Black women imprisoned twice the rate of White women.

In 1979, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women was adopted by the UN General Assembly and became an international treaty by 1981. The convention brought women to the center of human rights concerns. But U.S. state violence against Black women and children is long-standing, pervasive, multilayered, and deeply rooted in America’s beginnings.

Atty. Nkechi Taifa, author of “Black Power, Black Lawyer” told The Final Call America’s marginalizing of Black women and children is reflected in systemic racism like mass incarceration on women.

She sees the issue through the lens of the international convention against genocide which prohibits countries taking actions to prevent births within a specific ethnic or racial group.

“The genocide convention is the only convention actionable in U.S. law,” said Ms. Taifa. “If you’re going to be dealing with mass incarceration and incarcerating people during their prime childbearing years, you’re preventing births within that group,” she explained.

“When you’re gunning down teenage girls, using deadly force against them by using killer cops instead of having social services come in. You’re dealing with taking measures to prevent births within the group,” she added.

The International Commission of Inquiry wants U.S. lawmakers to support legislation aimed at pulling federal resources out of incarceration and policing and end legal system-driven harm that criminalized Black and Brown communities. To remedy the rights violations of the woman and child, America was also called on to ratify international human rights and regional treaties.

The commissioners also called on America to “fully enforce” the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, as well as the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which the United States already ratified.

The commissioners looked at U.S. practices and heard cases from over two decades. However, Mr. Hines explained that the commissioners combed data going back over 60 years and found a recurring pattern.

The current systemic problem between Blacks and police goes back to the role law enforcement played in 19th century slave codes, they found.

“That is the reason why we felt appealing to the courts, to the U.S. Congress, we have no expectation that we will get relief,” said Atty. Hines. “Hence we feel that the United States would have to be taken to a higher court, the international court in the international community,” he explained.

The push to uncover U.S. abuses before the world is necessary because America arrogantly represents herself globally as the standard to measure human rights.

“And yet they have dirty linen that they want to hide, therefore we are exposing the underbelly of the United States to the world community, for them to see,” stated Mr. Hines.