By Richard B. Muhammad – Editor

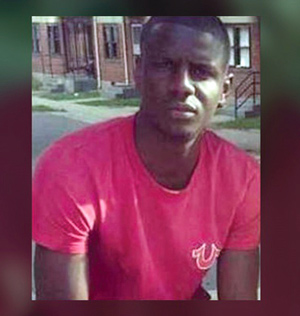

In Baltimore a jury was unable to reach a verdict in the trial of Officer William Porter, who was charged with manslaughter, assault, reckless endangerment and misconduct in the death of Freddie Gray. That must not mean deserting the fight for justice for the 25-year-old Black man who died after a ride in a police cruiser and injuries that separated his head from his spine.

What a horrible way to die.

Video of police putting Mr. Gray into a police cruiser, without seat belting him in as required by department policy, shows the victim was in great agony. He was moaning and could not walk as officers carried him to a paddy wagon. He was eventually bound hand and foot inside the police vehicle.

The reason why he was stopped by police was never crystal clear and the state’s attorney argued that the stop itself was illegal. What was clear is Freddie Gray lived in a neighborhood like many across the country, where Blacks live in fear of officers. In these Black communities, officers are an occupying force determined to keep an unwanted population contained and controlled.

Efforts to discover what happened when Mr. Gray was initially stopped and how he was so painfully injured from the beginning must not be abandoned.

A gag order has made it difficult to determine why the jury was unable to reach a verdict and the racial breakdown of the jury, seven Blacks and five Whites, along with the slim chances that police officers are charged let alone convicted made this a difficult case–regardless of what really happened or how it was prosecuted. You need 12 affirmative votes to get a conviction.

But justice requires more than just a finding that systems didn’t work, training was inadequate and portrayals of the Baltimore City Police Department, a force in a major city, as the personification of bumbling Keystone Cops. “The Baltimore Police Department is a clear loser in the no-win situation left by a hung jury in the state’s first effort to convict an officer in the death of Freddie Gray. Both defense attorneys and prosecutors portrayed the department as so dysfunctional its officers either aren’t aware of mandatory orders or ignore commands without consequence. First responders described being unfamiliar with first aid. Officers said they only check their email once a month, on old computers that barely work,” the Associated Press reported.

“Prosecutors portrayed Porter as a callous officer who intentionally failed to buckle Gray into a seat belt and didn’t call an ambulance even after Gray indicated he needed medical aid. But Porter said officers rarely belted prisoners, if ever, despite their general order requiring them to do so. He called it common practice to avoid calling ambulances,” the article continued.

Common or errant practices can’t be used to excuse failures that cost one life, altered perhaps thousands of others and spawned a tragedy that resulted in unrest costing millions of dollars.

The law and the need for accountability are always clear when Black folks appear before judges and juries, regardless of circumstances, misunderstandings or broken systems. The weight usually falls back on accused, not whether things went as they should–from arrests to respect for the rights of the accused.

But when it comes to police officers and those entrusted with upholding the law, there always appears to be a loophole, an out, a justification for not holding powerful persons responsible for acts that hurt others–especially when the others are Black, Brown and poor.

It’s outrageous that no ambulance was called for Mr. Gray from the beginning. But since Black Lives Don’t Matter, there was no need for that. Why follow any procedure when you are dealing with animals?

Respect and protocols are only important when you are dealing with White people. Black Lives Don’t Matter in a society entrenched in White Supremacy with systems and people inside the systems to keep Black people in check.

State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby did the right thing in charging all of the officers connected with the arrest of Mr. Gray and what happened while he was under police control. Officer Porter’s admission that he did not belt Mr. Gray in cannot be taken as an example of a departmental failure–it’s an admission that he failed in his duty and a man died. There should be no getting around that. The city has already paid out millions for injuries and deaths resulting from un-seat belted “rough rides” in paddy wagons. The department changed its policies as a result.

The entire police department is not on trial, specific officers are on trial and those officers must be held accountable for their actions. They cannot be allowed to hide behind an excuse we deny five-year-olds: “I did it because everybody else did.”

As Brandon Garrett, a University of Virginia professor who specializes in policing and civil rights litigation, told the Associated Press, “We know police departments have a bad culture of tolerating brutality, but it’s incredibly difficult to challenge a culture in a court case. It’s these officers who are on trial, but the reputation of the police department was irreparably damaged when Freddie Gray died.”

What happens to the police department is an entirely different matter, one to be determined by Baltimore residents, political leaders, administrators, voters, community and youth organizers and pressure on political and business leaders.

Officers who fail to follow procedures and who break the law aren’t scapegoats, they are criminals and must be punished as such.

–Richard B. Muhammad, editor-in-chief