Latino interest groups, including advocates for environmental justice, migrant, and farmworker rights, have been rallying across California’s Central Valley to demand accountability from government and corporate entities. They are also seeking to build coalitions to address decades-long health and environmental crises impacting these workers.

“We have programs that are concerned with air quality because we have the worst air quality in the entire United States,” said Nayamín Martínez in a telephone interview with The Final Call.

She is the executive director of the Central California Environmental Justice Network (CCEJN), an organization serving communities throughout the San Joaquin and Central Valley regions. Ms. Martínez suggested those endangered by and exposed to agriculture industry contaminants raise more than just moral concerns for companies and corporations using migrant farm labor.

“We are also concerned with fighting pesticides,” Ms. Martínez said. “Our area is the largest agricultural producing area in the country and because of that our region is where 61 percent of the pesticides (in the state) are concentrated, a lot of them near homes and schools where our communities of color live and study. We’re very concerned with water issues. There are still one million people in California that do not have access to safe and affordable drinking water,” she continued.

“A lot of these contaminants are byproducts of the agriculture industry, being fertilizers or pesticides, so we do a lot of advocacy work and try to find projects that offer short-term solutions when people have nitrates in their water or when they have (carcinogenic) 1, 2, 3, TCP (Trichloropropane), arsenic, or many other contaminants,” Ms. Martínez explained. “We also do a lot of work around oil and gas,” she added.

Kern County, which is a county in the Southern part of the Central Valley, is where about 80 percent of the oil extraction happens, said Ms. Martínez. “A lot of these oil wells are very close to schools, churches, homes, and we have been able to document massive leaks of methane and VOCs (volatile organic compounds), many of which can cause cancer, so we have been working so these leaks are repaired and to have protective measures (in place).”

Poisons in the land, food, and water

In 1967, the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad, Eternal Leader of the Nation of Islam, addressed in his landmark book, “How to Eat to Live,” Book One, about the use of commonly accepted chemicals and pesticides of that day.

He explained that the scientists and merchants of this world cared more for profits than for the health and well-being of the people. On page 107, he wrote: “Living under the guidance of the enemy of right and the god of unrighteous is a very dangerous position to be in.”

The Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad continued in part, writing, “The scientist should not advocate the use of such poisonous chemicals as fluoride, chloride and sodium, which may have a bad effect on our brains and our human reproductive organs. The scientist that uses such poison on human beings wants to either minimize the birth rates or cause the extinction of a people.”

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan has also addressed the problems associated with toxic chemicals used in food and water. In a 2004 end-of-year interview the Minister gave to The Final Call, he addressed what he called an “unholy alliance between pharmaceutical companies, agricultural conglomerates, chemical firms that produce pesticides and the Food and Drug Administration.”

“How can this unsuspecting public protect itself? In reality, it cannot, unless the public is made aware and the public’s will is to take control of the earth and what goes in it that produces our food.

Unless we are watchful of the chemicals that are sold to the agricultural conglomerates and unless we are watchful of the pharmaceutical companies and their desire to make money from the illnesses that are created by this unholy alliance, then we are locked in The Valley of the Shadow of Death,” Minister Farrakhan warned.

The fallout from these chemicals impacts the air, food and water of everyday people, particularly those who are often most vulnerable—poor workers and consumers.

According to its webpage, the EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) said they are “working with other agencies and local communities to address the unique environmental challenges in the San Joaquin Valley, including some of the nation’s worst air quality, high rates of childhood asthma, and contaminated drinking water.”

The government agency’s website also said the San Joaquin Valley is one of the world’s most productive agricultural regions and home to about four million Californians.

Despite the EPA stating that it oversees cleanup work at 14 Superfund sites throughout the San Joaquin Valley and that most of these sites have been completed, or are nearing final completion, questions still remain over the impacts and harm that the agricultural, oil, and gas industries created over the years.

“Superfund” is an informal reference to the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980. “When there is no viable responsible party, Superfund gives EPA the funds and authority to clean up contaminated sites,” the EPA website states.

Activists, interest, and advocacy groups continue to raise their voices to demand justice and to hold those in authority accountable for rectifying and solving these environmental problems.

Bianca Lopez is co-founder and project director of the Modesto, California-based Valley Improvement Projects (V.I.P.) for Social and Environmental Justice. She told The Final Call that her group is dedicated to social and environmental justice as a grassroots organization and that many communities dependent on wells for drinking and bathing are suffering hardship.

“Water wells are depleting,” Ms. Lopez said of the increased water usage related to drought and the agricultural wells drilled deep into the valley’s aquifers.

“Our water is contaminated in these wells due to agricultural runoff from animal feed and fertilizer, so we find a lot of nitrates and arsenic in our water. There are many communities across the Central Valley that do not have safe drinkable water,” she explained.

“Pesticides are an air contaminant, but they also contaminate our water and our soil, and I know there are many oil wells in the Southern end of the valley that are shut off that are still emitting methane,” Ms. Lopez continued.

“Some of the (oil) wells that are active have caused some emergency situations in neighboring communities.” She said these incidents led to additional regulatory and legal restrictions by the government which she sees as a step in the right direction. But more needs to be done, she explained.

More must be done to protect the most vulnerable

Nation of Islam Student Minister Abel Muhammad is representative to the Latin American and Spanish-speaking community for the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam.

He told The Final Call that he has heard the grievances of many documented and undocumented workers, who have suffered indignities because of lack of understanding as immigrants or because of language barriers.

“Unfortunately, it happens on so many levels, where those who are without documents and are really at the mercy of the bosses, the corporations, the workers, or the job site managers, who want to take the labor and the hard work of the brothers and sisters who enter the country from Latin America, the Caribbean, and other places, but don’t have the proper work permits or documentation to work legally,” Student Minister Muhammad said.

“If we take a serious and honest look at it, as those who eat from grocery stores and restaurants, we should not only have an awareness, but an appreciation for the source from which our food is coming from,” Student Minister Muhammad noted.

“It doesn’t just magically just show up on our tables at home. There are human beings who often go out in extreme conditions, extreme heat, long days, and take extreme care to try to harvest food that we then get at our homes to nourish ourselves and our families. But how often do we consider the lives of those who are in the fields and how they are treated?” he asked.

Regarding the problems of pesticide usage in California agriculture, Ms. Lopez cited data stating that at least 200 million pounds are used annually for crop production, about 20 percent of the national total.

This brings long-term and short-term environmental and health-related harms to Latino communities across California’s Central Valley.

“The Latino community lives and works on the fields or near these fields where pesticides are applied, so this not only becomes an environmental injustice but also a racial injustice as we know that Latinos are disproportionately affected,”

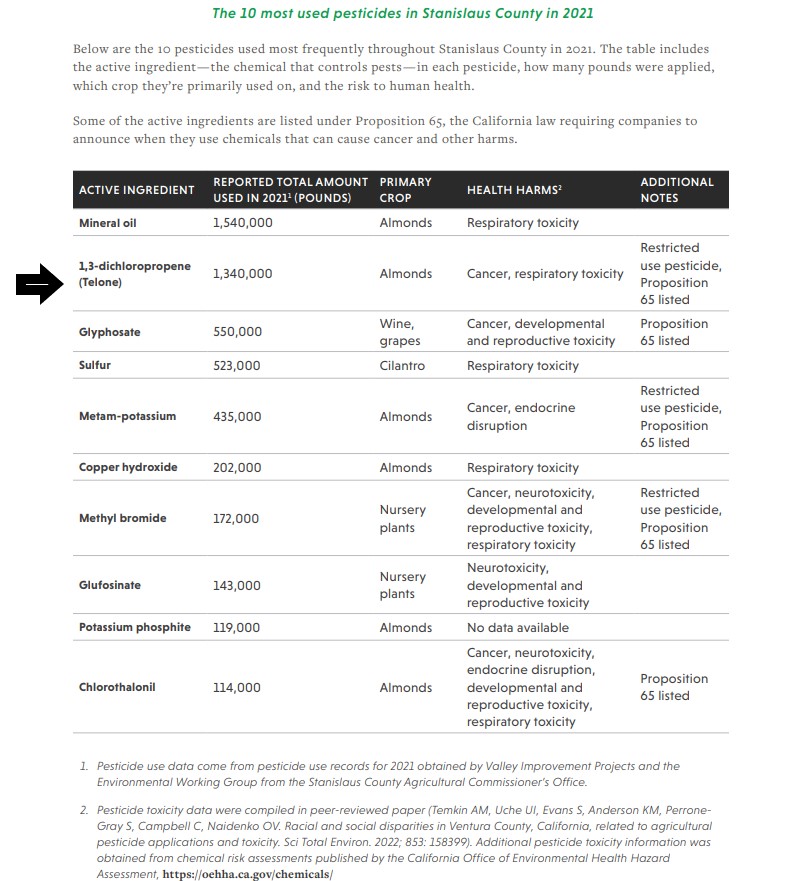

Ms. Lopez insisted. “Specifically, in Stanislaus County, we did a study with the Environmental Working Group (EWG) in 2021 and we found that approximately six million pounds of pesticides were applied in just that year.

“We have a map where we identified the high use of pesticides. We found that many schools are actually in what we call the red zones where high amounts of pesticides are being applied,” Ms. Lopez continued.

“One of our tasks is to make sure the parents are educated and informed and aware of the high amounts of pesticides that are surrounding these schools because it is children who are most vulnerable, their bodies are so tiny and still growing and because they spend a lot of time outdoors, they put their hands in their mouths and they are exposed much more than an adult.”

Citing a connection between corporate and political expediency on one hand, and what Ms. Lopez described as environmental racism on the other, she described how state regulators defined “acceptable levels” of toxic chemicals in pesticides because of industry politics versus disfranchised non-English-speaking workers who may be unaware of the gamesmanship perpetrated by those in high places regarding safety standards.

“The Department of Pesticide Regulation is the agency tasked with enforcing pesticide laws under the California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA),” Ms. Lopez said. “That agency is currently tasked with creating protective standards for the use of a toxic restricted pesticide called ‘Telone,’ which is the name of the product.

The name of the active ingredient is 1,3-D,” as identified in the Environmental Working Group (EWG) Fact Sheet, emailed to The Final Call by the Valley Improvement Projects. EWG is a nonprofit and nonpartisan organization.

“The Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) is the agency for the state that does the research and sets the limits,” Ms. Lopez explained, “but the Department of Pesticide Regulation is choosing a different protective level and is siding with the company that makes Telone,” she alleged. Ms. Lopez argued that protocols and procedures are not being followed as it relates to its level of toxicity.

The 1,3-D ingredient is identified “as a cancer-causing chemical under the state’s Proposition 65 warning and notice program,” according to EWG. “Once applied, it can drift—in this case—miles from the initial site of application.”

Luis Magaña, of OTAC (La Organizacíon de Trabajadores Agricolas de California / The Organization of California Agricultural Workers), is based in Stockton and was a contemporary of César Chávez, the famed farmer/migrant rights activist.

Mr. Magaña told The Final Call that one of their challenges is passing information to the newer immigrant and migrant workers coming from the Southern states of Mexico, such as Oaxaca. They tend to speak more Indigenous languages, making communication more difficult.

“I met with César Chávez two times, and he came to us to meet our first committee of farm workers in Stockton, and he explained about one of our main concerns and he did a presentation about it in Spanish and showed a documentary,” Mr. Magaña said of the Civil Rights and union leader who gained global attention for his national grape boycott ending in 1970.

“When he said to me, ‘what is the main issue you want me to talk about,’ (and) I said to Mr. Chávez, pesticides,” which, decades later, proved to be one of the major environmental issues facing California’s Central Valley.

“Later, the United Farmworkers Union (UFW) were not organizing so much in our area, (and) we needed to continue to fight more for immigrant rights and for farmworker rights, and that’s how in the ’90s, we formed OTAC,” Mr. Magaña said.

César Chávez would pass away later at 66 years of age on April 23, 1993, leaving a legacy of work and sacrifice for others to follow. Mr. Magaña, a respected elder in his community, continues to fight as a fearless advocate for immigrant workers to educate farmworkers on environmental justice, human rights, health care, access to proper food, proper pay, and multiple other issues facing agricultural workers.