by Yaminah Muhammad

NEW YORK—Fifty-three years ago, the New York State National Guard, state troopers and police officers violently repressed prisoner unrest and hostage-taking at Attica Correctional Facility, leaving at least 43 dead and nearly 90 wounded. All but one guard and three inmates were killed by law enforcement officials when they retook the facility.

On September 13 at Trinity Church in Manhattan, Attica survivors were joined by community members and political activists to honor the dead and wounded. Outraged by the continued escalation of prison incarceration and the abuse that occurs in those facilities, attendees also expressed their concerns.

“As we take the time to reflect on these incredible lives and the contributions that they made … we’d want to take a moment of silence to feel a moment of sadness without saying anything. But the best way to honor this group of people is to continue to be loud—it’s to resist, to be loud, to shout, to celebrate, to honor them.

This is not the time to be silent,” Emani Davis said in a video presentation played at the commemoration. Ms. Davis is the daughter of the late Attica prisoner Jomo Davis and Attica lawyer Elizabeth Gaynes.

After reading the names of the prisoners killed in 1971 and those who passed in the years following, Ms. Davis continued, “… we should in our remembrance continue to draw energy, strength and power from their commitment.”

The three-hour tribute, titled 53rd Attica Memorial, was presented by the Attica Brothers Foundation—an organization founded by Attica survivors to provide support for survivors of the Attica Prison Uprising and preserve archival material on the event.

The Foundation’s mission is to sustain the voices of Attica revolutionaries for future generations. In doing so, they welcomed Attica survivors to the microphone to tell their heartfelt, yet unsettling stories.

Tyrone Larkins survived the attack. Now president of the Attica Brothers Foundation, Mr. Larkins said, “Fifty-three years ago today, shot gun bullets went through my big afro. I had fragments on my head [and] my hand. I got shot in the leg, I got shot in the foot, but I’m here today, 53 years later.”

Overtaken by emotions, he acknowledged the lives of those he calls his “brothers” that did not make it, loudly declaring, “We cannot allow this to happen again on the planet.”

Attica [Prison Uprising] is a thing of the past but what people fail to realize is that these things can and will happen again if it isn’t told correctly. So, hopefully, by bringing attention to and remembering the story of Attica, we can prevent something like this from happening again,” Attica survivor Arthur Bobby Harrison, 76, told The Final Call.

Representatives from several Attica Brothers Foundation partner organizations were also in attendance, including the Alliance of Families for Justice and their Shut Down Attica campaign, Release Aging People in Prison Campaign, and American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker organization working with people of varying faiths and backgrounds to challenge unjust systems.

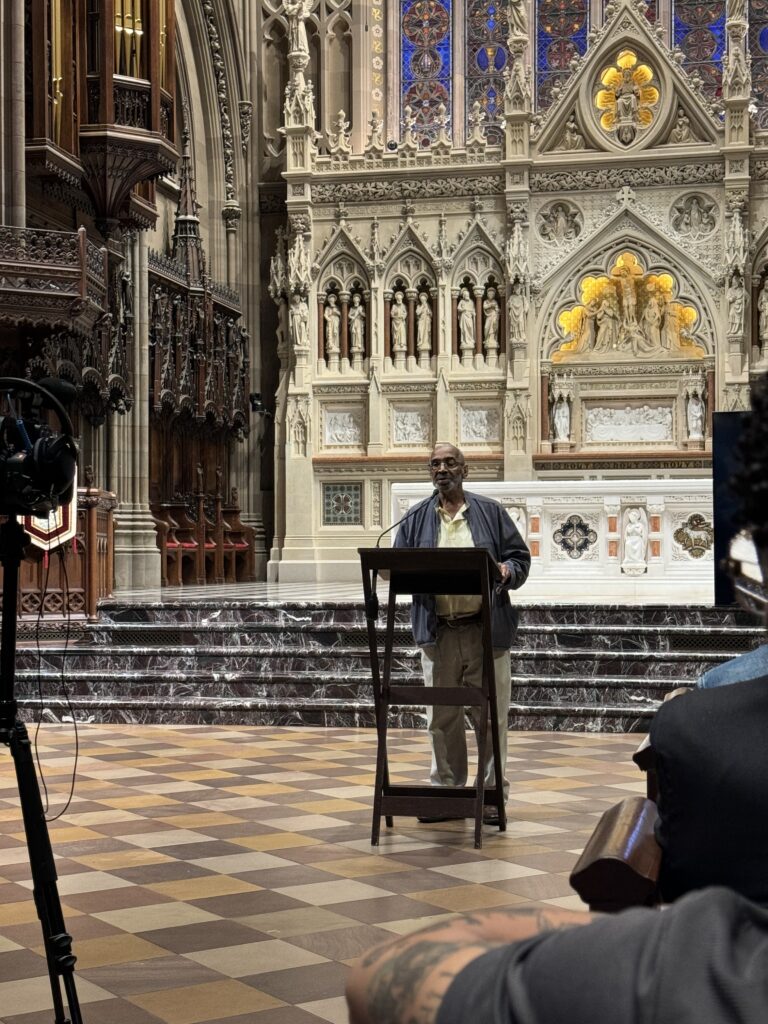

In detailing AFSC’s Healing Justice initiative, program director King Downing explained their plan to have Attica survivors speak to high school and college students.

“History has a way of moving into the background as the people who created it and lived it join the ancestors,” Mr. Downing told The Final Call. “It’s important to keep the fact that these were human beings, and they stepped up for a case and put themselves on the frontline. This generation has to hear this and learn the lessons.”

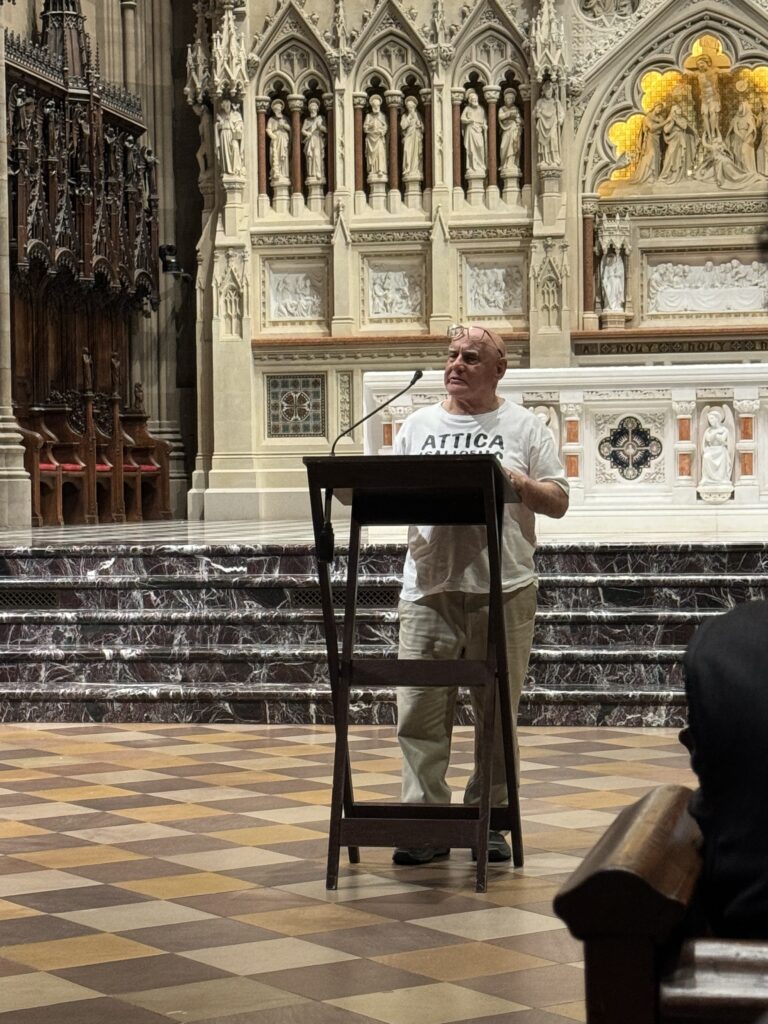

Lawyers from the Attica Prison Uprising also were on hand.

“The Attica story has to be a story of change. We have to not accept year after year the story of a massacre,” said Attica lawyer Dan Meyers, a member of the legal team that pursued civil litigation against the state for the deadly retaking of Attica Prison. Their work helped put the Attica Brothers on offense.

Attorney Meyers called on audience members to join the 13th Forward Coalition in their fight to advance the “No Slavery in NY Act” and the “Fairness & Opportunity for Incarcerated Workers Act” to eliminate practices of slavery and exploitation against incarcerated people.

“This is something that’s a kind of legacy of how we act back at the horror of the Attica massacre and the vast hopes of the Attica Rebellion,” he added.

Attica explodes

On September 9, 1971, Attica Correctional Facility, an overcrowded New York maximum security prison for males, was taken over by 1,000 prisoners, mostly poor Black and Latino men.

The prisoners protested inhumane physical and physiological treatment inflicted on them by all-White male prison guards. In hopes of making systematic change, the inmates presented a manifesto of over 20 demands to then New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, Corrections Commissioner Russel Oswald and other New York officials.

Demands included the implementation of a minimum wage, rehabilitation programs, appropriate medical treatment, and educational opportunities. Although Mr. Oswald agreed to many of the demands, the inmates rejected his offer due to the refusal to include amnesty for participants in the uprising.

After four days of televised protest and political negotiations, Gov. Rockefeller ordered the New York State National Guard, state troopers and New York police officers to retake the prison. Authorities dropped tear gas into the facility’s yard and shot over 2,000 rounds of ammunition into the smokey haze.

According to troopers.ny.gov in all, 43 people lost their lives in the uprising, including 11 Corrections Officers. Survivors of the massacre were then subjected to torture, sexual assault, and death at the hands of authorities.

Despite its fatal effect, then President Richard Nixon saw the inmate casualties as justified and a positive political act. In a taped phone call with Governor Rockefeller, President Nixon stated, “This might have one hell of a salutary effect. They can talk all they want about the radicals. You know what stops them? Kill a few.”

Though Nixon’s remarks were hidden from the public at the time, the discovery of them now left many at the commemoration to believe that American authorities experienced a sense of enjoyment in the brutality of Attica inmates.

Survivor Che Nieves described authorities as seemingly, “having a wonderful time killing people.” He detailed feeling officials urinate on and repeatedly kick his body as he laid defenseless on the prison floor following their retaking of the prison.

Attica and modern system parallels

From proper healthcare to rehabilitation, incarcerated people are often overlooked in the call for rightful and humane treatment. Advocates argue that those living within the prison system habitually face a total disregard of their humanity as they are denied basic civil and human needs. Therefore, leaving them to fight for freedom, justice and equality from the prison system while locked inside of it.

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan in a message titled,

“Death Stands At The Door,” delivered July 27, 2003 spoke about Attica. He recalled he was looking at television to find out how many U.S. soldiers had lost their lives during the Iraq war “due to the blunder, the arrogance and the folly of the President of the United States.”

“As I was turning the dial, I saw what was a documentary on the rebellion that took place at Attica prison and the Black Brothers who were killed as a result of their trying to get better treatment. Even though they were prisoners, they wanted better treatment in that hell hole called Attica prison,” Minister Farrakhan said.

“As a young minister of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, I taught in all of the prisons in New York State, including Attica. Looking at that television and reflecting on my work in the prisons, I paid even closer attention to the documentary,” he added.

During his message, Minister Farrakhan reflected on his work on behalf of the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad in many of America’s prisons. When the Attica uprising occurred, Minister Farrakhan stated he was asked to mediate so he contacted the Honorable Elijah Muhammad for guidance and permission. At first, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad gave permission, but just as the Minister was about to board the plane to go, his teacher told him not to.

“The governor of the state of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, was sending a plane to fly me from New York City to Attica prison, which is near the Canadian border. Just as I was about to leave to get on that plane, I got another call from the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. He said, no, Brother, don’t go.”

“It’s wonderful to have a leader on whom you can rely and in whom you can put trust to obey. In truth, I wanted to do whatever I could to ease the situation of our brothers who had now taken part of the prison and had many White hostages.

And in less than 24 hours, they were killing our Brothers wholesale,” the Minister said. He shared that it could have been, he was asked to go so that something unfortunate would happen to him.

“When I saw the slaughter (at Attica), I literally wept because I wondered if I could have in any way made a difference and saved some of the precious lives of those beautiful Black men.

Looking back at the documentary, I realize now that the worst slaughter took place after the uprising once the guards had re-taken control of the prison. It touched me so deeply because it gave me a reminder of the nature of the enemy in whose hands we are, and what we are about to face.”

The uprising brought mass attention to the fight for fair treatment of inmates. On display for the world to see, the “riot” exposed the American prison system to be a horrifying extension of chattel slavery.

Since then, a lot remains the same in the prison system across America—allowing clear parallels to be drawn between prison life from then to now. Similar to the 1970s, Black and Latino people of lower social and economic classes account for a majority of the imprisoned population.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Black and Latino people make up roughly 56 percent of all people incarcerated in America with Black people being the majority at 32 percent. This reflects a massive disproportion as Black and Latino people are reported to only makeup 31 percent of the U.S. population, according to the U.S. Census.

In addition to demographic similarities to the 1970s, living conditions also remain alike. With few efforts at truly reforming America’s incarceration industry having been thoroughly implemented within the system, prisoners continue to face extremely poor and violent living conditions. This ranges from mental illness, solitary confinement to improper health care for the physically sick.

Criminal justice reform advocates tend to agree.

“We haven’t changed enough to say we’ve reformed our incarceration system,” said Jennifer Vollen-Katz, executive director for the Illinois John Howard Association, a prison reform advocacy group. “It’s been one step forward, several steps backward.”

She said the “super predator” and “tough on crime” public narratives led to approaches such as truth in sentencing and mandatory prison sentencing that overcrowded facilities.

“The political tone was ‘tough on crime.’ [Politicians] were not winning elections talking about prison reform,” she told The Final Call.

Wanda Bertram, a spokesperson for the Prison Policy Institute, said the demands from Attica are relevant today.

“It’s more common for prisons to go into lockdown for days and weeks now” than in 1971, she told The Final Call. “There has been no change because prisons are places to warehouse people the state doesn’t want to take care of.”

Vollen-Katz and Bertram said Attica’s demands for adequate medical treatment and legal representation, improved visitor conditions and an end to physical abuse by guards are still needed. Treatment for mental illness and changes to parole for early release are critical issues, they say.

“We’ve got a long way to go before we can call our system humane. We need to find ways to increase transparency and oversite. Leaving a closed system to police itself is a bad idea,” Vollen-Katz said.

Audience member Veronica Nickey, 57, hopes knowing the racist parallels between Attica Correctional Facility and today’s prisons will encourage young people to do their best to not only fight against, but also stay away from the prison system.

“If young Afro (Black) people knew the true history and narratives of how bad we were treated in the prison system, it could help them stay away from the trick of being incarcerated,” the retired licensed nurse told The Final Call. “It would also keep them from engaging in activities that put them in prison,” she added.

Final Call Contributing Editor James G. Muhammad and Final Call staff contributed to this report.