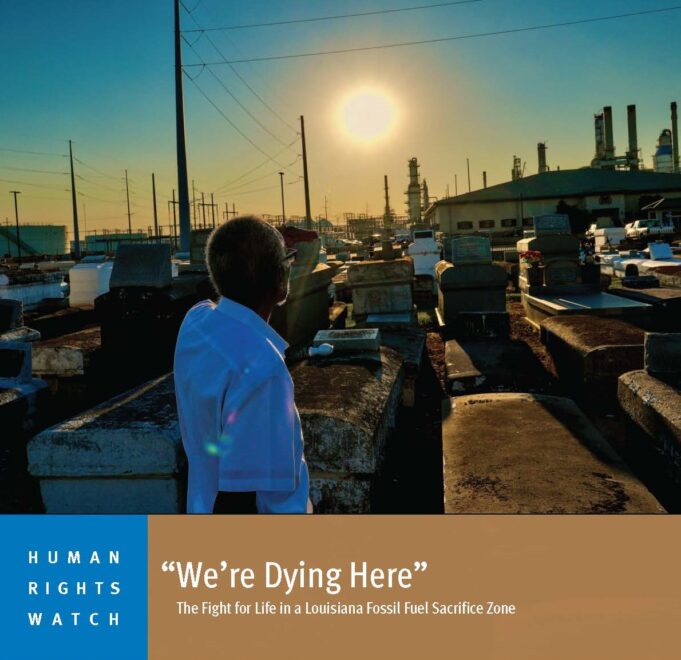

Robert Taylor II, 83, lives in the small town of Reserve in St. John’s Parish, Louisiana, dubbed “Cancer Alley” because of sprawling chemical plants that release toxic pollutants into the air and water.

But on August 22, U.S. District Court Judge James Cain Jr. issued a ruling permanently blocking the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Department of Justice (DOJ) from enforcing disparate impact regulations under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in the state.

For decades, predominantly Black communities like his, located on the east bank of the Mississippi River, between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, have been disproportionately affected by environmental hazards.

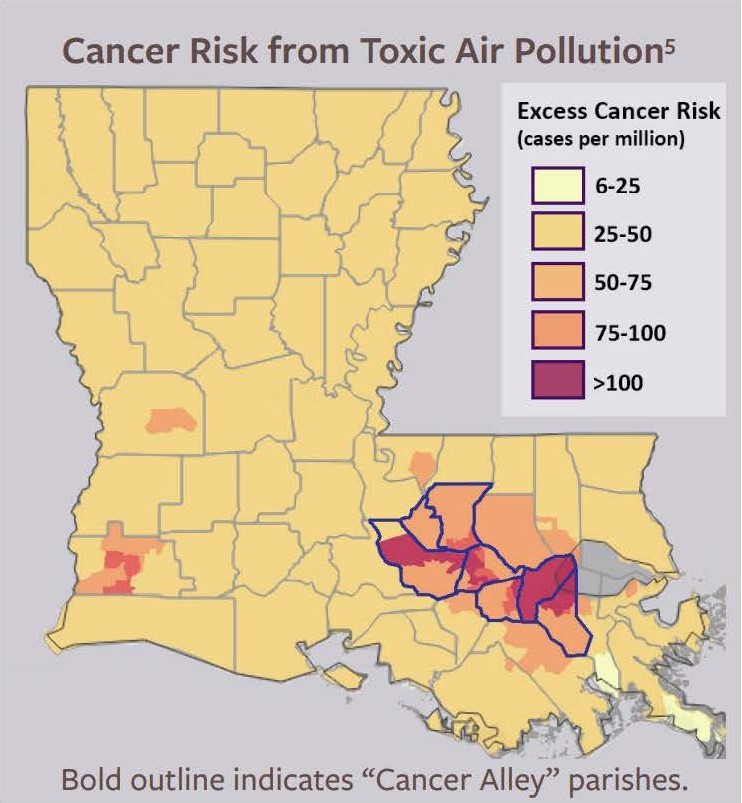

Children suffer from significantly high rates of asthma and adults face alarming rates of cancer, 50 times higher than the national average (1,500 per million people), according to federal regulators.

Mr. Taylor and other residents, activists and legal advocates have been fighting this environmental injustice since 2016. “This is genocide. They target the Black community,” Mr. Taylor told The Final Call. That year, he founded the Concerned Citizens of St. John Parish to advocate for their health and safety.

“What the state is doing, I don’t understand how the federal government is allowing this to happen to the poor, defenseless people here,” said Mr. Taylor. These fence line communities, like the one I live in, that is totally devastated by this corporation, DuPont/Denka and what they’re doing.

And a Christian society, to even consider tolerating what this industry is doing,” he continued, referring to U.S. chemical giant DuPont and Japanese-owned chemical plant Denka. Both have operated the plant that produces cancer-causing chloroprene and have been sued by the Department of Justice over the issue.

“How could there be over 200 petrochemical plants concentrated in an 80-mile area along the river with a 94 percent Black population? Where did all the White people go,” questioned Mr. Taylor. He argued that the U.S. government is not just paving the way for more Black deaths but, “They’re guaranteeing it.”

He was born in Reserve, where sugar cane plantations were replaced with petroleum and chemical plantations.

“I’ve watched this. I’ve witnessed this. I’ve suffered from this. My mother died of cancer. I could go around a litany: my brother, my sister, my nephews. Right now, I’ve got a 34-year-old nephew, who’s where that plant is, right on the fence line.

He’s lost his brother and his sister to cancer, and now he has cancer. Thirty-four years old, and it’s happening every day in our community, all around us, and it’s a horrible death,” Mr. Taylor added.

In January 2022, Earthjustice, a nonprofit public interest environmental law organization, and Tulane Law School advocates filed civil rights complaints on behalf of St. John the Baptist Parish and communities living close to disproportionate exposures to environmental harms. The advocates argued that the State of Louisiana’s agencies had been discriminating in their decision-making about pollution.

Earthjustice asked the EPA to investigate whether Louisiana agencies had violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act by failing to protect Black communities from disproportionate environmental harm, according to Debbie Chizewer, managing attorney for Earthjustice’s Midwest office.

Title VI provides that no person in the U.S. shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.

After investigating, the EPA issued what’s called a “letter of concern” to Louisiana agencies, informing them of the probe and that it would be taking a close look, said Atty. Chizewer.

In response, she said, Gov. Jeff Landry, then attorney general of Louisiana, sued (in May 2023) and asked the court to prohibit the EPA and DOJ from enforcing a part of the civil rights laws in the Pelican State, and the judge granted that request.

Judge Cain’s ruling is a move that stops the federal government from addressing disparate harm in project permitting, compliance and enforcement of environmental laws, as well as provision of basic services such as sewage, drinking water, and health services, said Earthjustice in an August 23 news release.

There is a concerted attack on civil rights laws and environmental laws happening in the courts and with administrative agencies right now, stated Atty. Chizewer.

Conservative attorneys general (AGs) are saying that the EPA should get rid of protections for communities that protect them when laws seem neutral on their face but actually have disparate adverse impact on the communities that are protected under U.S. civil rights laws, Atty. Chizewer explained.

Communities that are protected include Black, Latino, Indigenous and other non-White communities, people with disabilities and others as well, she stated.

According to Atty. Chizewer, both civil rights and environmental laws are needed to protect communities, particularly communities of color, and Louisiana has not been doing a good job of enforcing its environmental laws.

Judge Cain ruled that Title VI requirements amount to government overreach, saying that “pollution does not discriminate.”

However, even United Nations human rights experts have raised serious concerns about further industrialization of the so-called “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana, saying the development of petrochemical complexes is a form of environmental racism.

In 2021, UN experts concluded similarly that the petrochemical corridor along the lower Mississippi River has adversely affected its mostly Black residents.

Further, the UN experts expressed, in a March 2021 news release, concerns at possible violations of the cultural rights of the impacted Black communities in the area, where at least four ancestral burial grounds of enslaved Africans are at serious risk of destruction by the construction of the Sunshine Project. In 2018, the project was approved by the St.

James Parish Council, according to the news release, and would be one of the largest plastics facilities in the world to be developed by a subsidiary company of Formosa Plastics Group. The Parish Council also approved plans to build methanol complexes by two other companies, the news release stated.

“The African American descendants of the enslaved people who once worked the land are today the primary victims of deadly environmental pollution that these petrochemical plants in their neighborhoods have caused,” stated the UN experts in their release.

“We call on the United States and St. James Parish to recognize and pay reparations for the centuries of harm to Afro-descendants rooted in slavery and colonialism,” it added.

Environmental injustices like “Cancer Alley” go unnoticed or exist for so long because it has been planned and executed, argued Mr. Taylor. Some say they are just finding out about it, to which he urged, “Just Google sacrifice zone and you’ll be surprised.”

Sacrifice zones are areas where residents are more likely to die of cancer and other illnesses earlier than people in nearby communities. They are often low-income communities of Black, Latino, Indigenous and poor people.

ProPublica has created a map of U.S. sacrifice zones that identifies around 1,000 hotspots and allows users to look up their home to see if they are living in a sacrifice zone.

“I’ll say they’re not unnoticed by the communities that can’t breath and who can’t drink clean water. It’s truly unconscionable how long these injustices have been experienced and that is why we need our civil rights laws,” stated Atty. Chizewer.

According to Atty. Chizewer, environmental laws aren’t doing enough on their own and the civil rights laws fill in that gap, adding that protection of air and water cannot depend on one’s zip code and that everyone must be entitled to those basic rights.

“EPA had a long history of not enforcing the law and has been catching up, trying to do work to enforce the laws and this is a push back by conservative AGs who are prioritizing profits over people,” Atty. Chizewer argued.

In addition to Louisiana, which now doesn’t have the protection that residents in other states have, other studies include the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency’s agreement with the EPA, where it recently agreed to change its permitting practices so that it will do more to consider cumulative impacts, she continued.

By cumulative, the attorney explained that means, “You live in a community, and after you move in, one facility opens, and then that’s exposing you to harmful pollution that’s affecting your ability to breathe and could affect your cardiovascular system.

But then, over the course of 10 years, five more facilities open, and that’s just adding to the health impacts of residents in those communities.”

“And that’s exactly what happened in Flint, Michigan, where, over the course of 30 years, more and more facilities have been placed in close proximity to housing and has really harmed the community,” said Atty. Chizewer.

One of the ways communities like “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana are affected is the concentration of industrial activities in a small area adjacent to their homes, she explained.

In the Illinois example they are going to change the way they do permitting, so that they consider those impacts up front, she said. Other states are trying to understand the disproportionate exposures before making permitting decisions and she thinks that’s a shift that must happen.

Time and time again, race has manifested as the biggest predictor of where hazardous waste will be collected, so that’s the basis, and why it’s not enough to just rely on environmental laws, she said, noting that there are lots of other tools and these baked-in inequities being perpetuated today must be addressed.

“It isn’t right for the residents of one state to not have this protection while others do. And it’s not right that people have to live in the place where they’re likely to get cancer or have breathing issues like asthma or cardiovascular issues just because of their zip code or their race,” she added.