CHICAGO—Judicial Watch, a conservative, Washington, D.C.-based organization, has filed a class action lawsuit to stop the city of Evanston, Illinois, from paying $25,000 in reparations to each of its Black residents.

The lawsuit, submitted on May 23 in the U.S. District Court of Northern Illinois in Chicago, names six non-Black plaintiffs and challenges the constitutionality of the city’s reparations program, arguing it discriminates against non-Black residents.

In 2021, Evanston made history as the first U.S. city to implement a reparations program for Black residents, led by former 5th Ward Alderman Robin Rue Simmons. The city passed an ordinance by an 8 to 1 vote, creating a $20 million program to pay $25,000 each to Black residents whose ancestors suffered from housing discrimination during segregation.

Ms. Simmons now serves as the chairperson of the city’s Reparations Committee, which oversees the initial Restorative Housing Program that began disbursements in January 2021. The payments, usable as down payments on homes or for home repairs, are part of a $10 million commitment over the next decade.

To date, Evanston has distributed $5 million to 193 Black residents and plans to extend payments to 80 more direct descendants. Inspired by Evanston’s example, several other governmental entities across the country are actively pursuing similar initiatives.

“This attack on Evanston is really an attack on the movement, an attack on Black hope and possibility, and self-determination. It’s an extension of the attacks on Affirmative Action and similar initiatives,” said Ms. Simmons in an exclusive Final Call interview. She is the founder and executive director of FirstRepair, a not-for-profit organization that informs about local reparations efforts nationwide.

“The complaint involves six White, non-Evanston residents suggesting they have a claim to reparations as well. Judicial Watch, the organization behind this, is known for suing and intimidating organizations across the United States, and we are their most recent target,” she said.

According to Judicial Watch documents, the plaintiffs assert that they are eligible because they had relatives who lived in Evanston. However, the lawsuit says that none of the plaintiffs or their relatives identify as Black.

“This lawsuit is about stripping away the hope and joy that Black residents have felt in receiving reparations and the possibility of full repair in our future. Evanston is a small city and setting aside $20 million to begin the process of repair is only a first tangible step,” added Ms. Simmons.

Evanston is located in Cook County, Illinois, about 12 miles north of downtown Chicago.

“When other cities and states, including large cities like Chicago, San Francisco, and Detroit, as well as small cities like Amherst and Asheville, and economically powerful states like California, New York, and Illinois, each pass reparations task forces, you know we are onto something significant. We are getting closer to the repair we’ve been fighting for, for centuries and generations in this nation,” Ms. Simmons said.

Pushback against reparations for Black people is nothing new. As early as 1862, even before all Black people knew slavery had ended, the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act provided $300 to former slave owners for each person freed but offered no reparations to the formerly enslaved.

Three years later, General Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15, commonly known as “40 acres and a mule,” aimed to allocate land to formerly enslaved people. But this order was reversed by President Andrew Johnson.

In 1866, the Southern Homestead Act sought to help freed Blacks become landowners, but it failed due to bureaucratic obstacles and was repealed in 1876.

Judicial Watch contends the reparations program’s “race-based eligibility requirement” violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The plaintiffs, represented by Judicial Watch, include Margot Flinn, Carol Johnson, Stasys Neimanas, Barbara Regard, Henry Regard, and Stephen Weiland.

The lawsuit argues that Evanston’s program should be based on individual experiences of discrimination rather than race. Judicial Watch President Tom Fitton criticized the program as a ploy to redistribute tax dollars based on race, calling it unconstitutional.

“They have filed lawsuits against the city of Evanston, and one thing that I was very sure of from the beginning when I questioned reparations in 2019, is that this day would come,” added Ms. Simmons. “The White supremacist community would not let this progress and these great milestones that are inspiring a national movement go unanswered.

Now, over 100 localities have taken steps towards reparations like Evanston. At that time, I asked that our law department be staffed on the reparations committee, and that’s been the case.”

Evanston spokesperson Cynthia Vargas stated that the city would not comment on the litigation but would “vehemently defend any lawsuit brought against our city’s Reparations Program,” according to a report by the local newspaper. However, the city’s history of racial discrimination is well-documented.

Blacks began arriving in Evanston in the 1850s, and by 1940, the Black population had grown significantly due to the Great Migration. Black residents were often confined to the city’s West Side, subjected to redlining, and denied access to various public amenities and services.

In response to systemic discrimination, the NAACP established a branch in Evanston in 1917, and Black residents formed their own institutions, including the Emerson Street YMCA and Boy Scout troops. Northwestern University did not fully desegregate its dormitories until the 1960s, forcing Black students to find alternative housing.

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson recently signed an executive order to create a task force focused on reparations for the city’s Black residents. The task force will study historical policies and their impact on Black Chicagoans, issuing recommendations and remedies.

This executive order follows Mayor Johnson’s allocation of $500,000 in the city’s fiscal 2024 budget towards reparations.

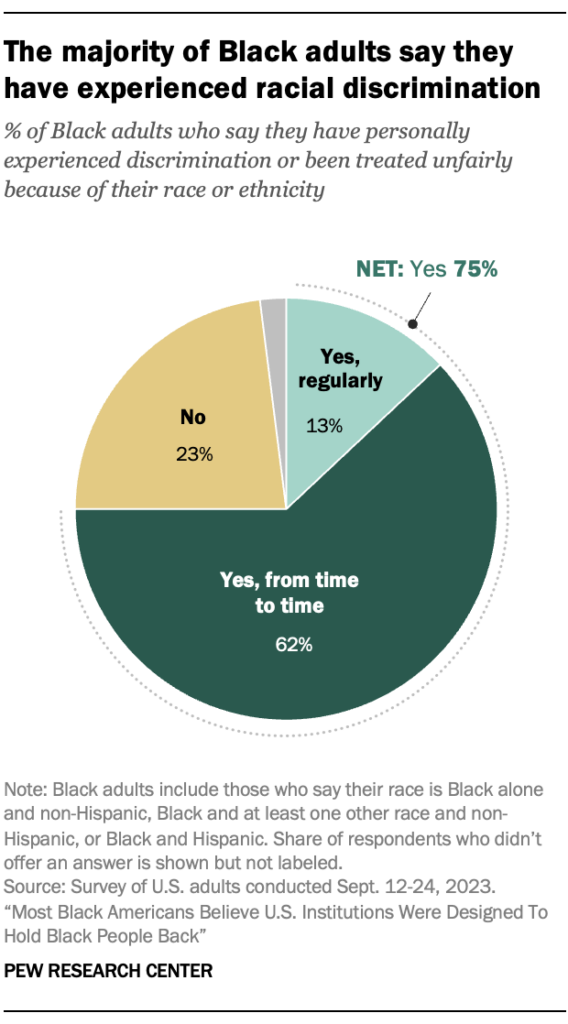

Reparations discussions have been ongoing, with advocates citing continued discrimination post-Emancipation. Reparations can take various forms, including financial payments, land grants, or social service benefits.

Evanston’s program, which allocated $400,000 for housing grants in 2021, set a precedent for local reparations initiatives. Mayor Johnson’s executive order reflects a commitment to addressing historical and present-day racial inequities in Chicago.