ATLANTA—At the African American Mayors Association’s (AAMA) 10th annual conference held in Atlanta, Black mayors convened to discuss some of the challenges facing their cities and the strategies they employ to deal with them.

“As mayors, we represent small towns and cities and villages, and we represent big metropolitan areas, but we are all dealing with very similar issues.

The only difference is the number of zeros that go behind our budget and the zeros that go behind our population,” Mayor Shawyn Patterson-Howard of Mount Vernon, New York, and former president of AAMA, shared at the conference’s opening plenary session on April 25. The gathering was held the last weekend of April. (See The Final Call, Vol. 43 No. 32)

Homelessness

Homelessness was one of the major issues tackled at the conference. Mayor Patterson-Howard voiced that many of the cities are facing affordability and housing crises, with Black people being overrepresented in the homeless population. The mayors discussed how they are tackling the root causes of homelessness.

Mayor Errick D. Simmons of Greenville, Mississippi, worked with faith-based institutions to develop “The Sacred Space,” a program providing meals to the homeless and a space to talk about mental health and drug abuse. Mayor Simmons is also tackling homelessness by curbing mass incarceration and through the city’s reentry and training program.

In Mount Vernon, Mayor Patterson-Howard is dealing with people piling up into one- and two-family houses, also causing more fires. She said that on her block, 28 people were living in a two-family house, which resulted in a major fire.

“It was down the street from me, and we had an autistic man, 35 years old, who died in that house that day as I stood outside and I watched my firefighters fight,” she said.

She spoke on how children are doubling and tripling up in basements and kitchens. In one home, 20 young people under the age of 25 used a five-gallon bucket to turn a closet into a makeshift bathroom.

“This is how a lot of our people are living. And you have to look for them, because I promise you, somewhere in your community, you have people who are tripled up. And so, we have to look at the couch surfing, and we have to look at the hidden homeless,” she said.

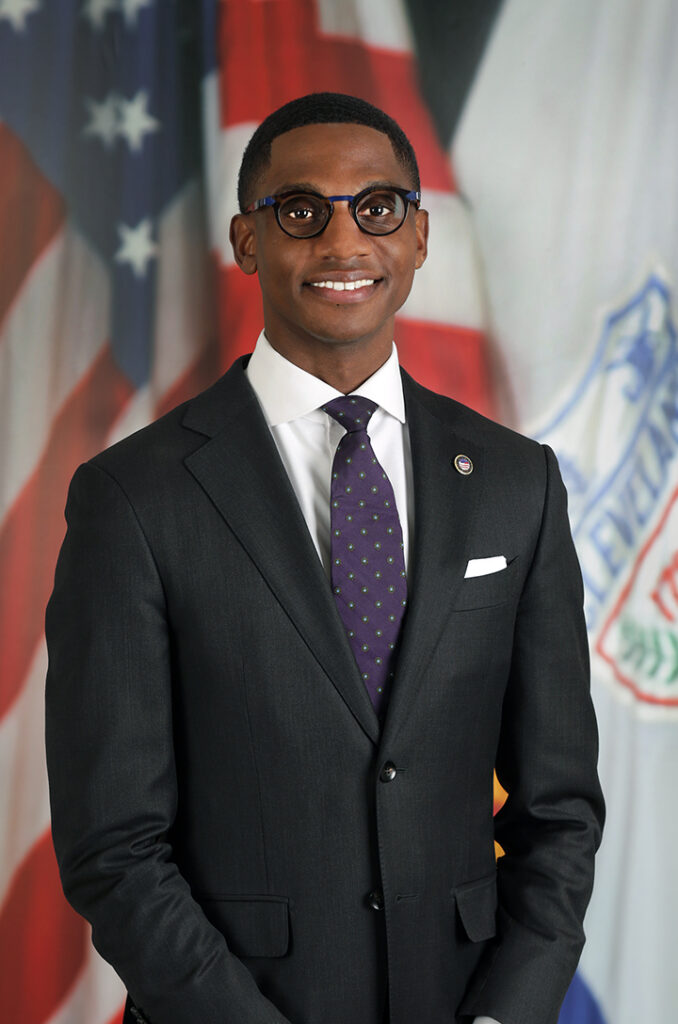

Mayor Justin Bibb of Cleveland, Ohio, commented on the housing issues in his city. He launched a program called “a home for every neighbor,” with the goal to house up to 150 people. The city also gave away a city park, where 42 low-to-moderate income housing units have been built.

Public safety and policing

Another major issue discussed throughout the conference was public safety and policing.

Mayor Paul Young of Memphis, Tennessee, who was just sworn in four months ago, recently launched the Black Mayors’ Coalition on Crime. The coalition held its first set of meetings in March, where they dialogued about holistic public safety. The Black mayors have been big on prevention and intervention.

Mayor Tishaura Jones of St. Louis, Missouri, shared that in the three years since she has been mayor, homicides have decreased by 40 percent, through her efforts in partnering with community organizations and utilizing trusted messengers that offer alternatives to a life of crime.

Part of enforcement includes developing alternative methods of response, “because police are not the person to answer every call that comes into our 911 facilities,” she said.

Those methods include a “cops and clinicians” program that pairs officers with behavioral health professionals and embeds behavioral health professionals in the 911 center to provide real-time help.

Mayor Patterson-Howard listed five pillars when it comes to public safety: prevention, intervention, diversion, enforcement and restorative practices.

“If we take as much of our funding and our energy in investing in all five of those pillars, the enforcement piece will not be such an issue,” she said. “We have to make sure that our approaches are balanced and that they’re equitable and that we’re partnering with all of the community in doing this.”

During an April 26 town hall meeting held at Morehouse College, panelists discussed what they are doing in their cities to address community restoration. Through community violence intervention programs, workforce development programs, housing and mentorship programs, homicides decreased significantly in Mount Vernon, New York.

Mayor Patterson-Howard has also been working with the Department of Recreation and the city’s youth bureau to have more community outreach events and festivals. She has been bringing in peace officers and has established a young adult emerging justice court, alongside reentry programs.

For Mayor Simmons, public safety is about meeting the people where they are.

“We have community events where we are able to listen to the brothers. And when you hear, for the most part, they just have that basic need to belong and love. They’re missing that.

And some of them are out there on the streets, really providing for their brother and sister in the house, because mama is working, there’s no daddy there. And so we have to create those opportunities not only for outreach but opportunities for them to let go,” he said.

The city has a “pathways to possibilities” program, where justice-involved youth get an opportunity to see different pathways to make money.

“Nothing stops a bullet like a job,” Mayor Bibb said. “I think we all recognize, as Black mayors, especially, that we can’t police our way out of this challenge and problem.”

Climate and environment

Throughout the conference, Black mayors discussed climate and environmental justice, including flooding, fires and intense heat.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba of Jackson, Mississippi, has been dealing with the effects of the city’s 2022 water crisis, along with freezing temperatures and flooding. The city was allotted $800 million from the federal government to improve its water system.

Mayor Lumumba said the funds were due to the residents lifting their voices. Now, the mayor is fighting against a bill that would create a state-appointed water authority over Jackson. He accused the state of trying to take over the city.

Also in Mississippi, Mayor Simmons is seeing $246 billion in disaster losses.

“The only way we can really combat this environmental justice crisis right now is to deploy nature-based infrastructure,” he said.

In the Midwest, Missouri sits as a landlocked state, and Mayor Tishaura Jones of St. Louis often deals with extreme heat and flooding.

“St. Louis sits at the confluence of the greatest rivers in our country, the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers, and we’re susceptible to flooding as a result of that,” she said. “The summer of 2022, we saw flooding not only in White communities, but in Black communities as well as a result of our failure to address a lot of infrastructure issues.”

She has several collaborative initiatives to address the climate issues in her city. She explained that one of the solutions to deal with extreme heat is to plant enough trees in order to create shade and eliminate heat islands. The city received an $8 million grant to help in that effort.

Mayor Patterson-Howard shared that her city deals with sewer and flood issues.

“I’m out in my car, in my truck with my detail and we’re riding around, because I’m finding families literally standing in front of their greatest asset in tears, breaking down because they have six, seven feet of water in their basement,” she said.

And most people don’t have flood insurance, she noted.

“When I became mayor, I was like Jay-Z: I got 99 problems, and environmental justice is not one of them,” she said. “We’re dealing with housing and crime and mental health and the things that we are usually looking at in many of the urban communities, but environmental justice has become the area that I’ve had to learn more and stand more than ever before in my mayoralty.

“Now we’re talking about tree canopy. Now we’re talking about heat islands. Now we’re talking about solar panels and things that we heard people talk about years and years ago, but now we’re talking about them because it’s impacting our communities at a greater rate than it is any of the other communities,” Mayor Patterson-Howard added.

“With rising costs of electricity, when you have no tree canopy and the neighborhood over here is five degrees to seven degrees hotter than it is in a tree-lined community, your utility bills cost more. And if you were struggling to pay for food and struggling to pay rent and mortgage, now you’re struggling to pay your utility bills.”

Health

Another policy session occurred on the topic “Addressing Social Determinants of Health Through Community Partnerships.” It was facilitated by Mayor Patterson-Howard, who spoke on the importance of culturally competent care and having courageous conversations about health.

“I know as a Black woman, as many of us as Black women, health care is sometimes the last thing on our mind. We are busy taking care of community, family, church and our partners that we put our health last. And so, when I speak to my doctor, they oftentimes push me and say, ‘Look, we need you to come back.

We need you to follow up. We need you to do what you need to do, because if you’re not taking care of yourself, then you can’t take care of everyone else,’” Mayor Patterson-Howard said.

Panelists Dr. Valerie Montgomery Rice, president and CEO of Morehouse College of Medicine, and Dr. Clyde Watkins, a primary care physician with Village Medical, touched on the importance of care persons developing trust with their patients.

Dr. Rice also shared the healthcare disparities she sees most in the Black community, including cardiovascular disease, maternal health and cancer. She cited statistics that the U.S. is ranked as a developing nation when it comes to maternal mortality and that Black women have three times the amount of deaths related to maternal issues compared to White women.

Dr. Watkins spoke on how primary care has changed into a team sport.

“We need to understand what the health status is of our communities. We need to put together healthcare teams that may include not just the doctor and your medical assistant, but it may include a clinical pharmacist. It may include social workers, nutritionists,” he said.

He urged the mayors to expand their definitions of what the “team” is.

“Understand that as leaders, you are part of that healthcare team. If you see that there’s a need in your community, talk to your community, find out what their needs are and approach it just like you’re bringing businesses into that community,” he said.

“You’re going to bring healthcare into that community as well, and the basis has to be primary care. If you want to get ahead of diseases, if you want to prevent chronic diseases, investing in primary care is leading from the front.”