ATLANTA—Black mayors matter. That phrase was repeated throughout the African American Mayors Association’s (AAMA) 10th annual conference, which was held at the Omni Atlanta Hotel on April 24-27.

About 100 Black mayors convened under the theme, “Striving Forward: Our Moment, Our Mission.”

The conference was kicked off with a “State of Our Cities” news conference on April 24. Topics and discussions across the four-day conference included broadband and infrastructure, technology and innovation, health and education, economic development, sustainability and climate change, building Black generational wealth, public safety, food insecurity, homelessness and public/private partnerships.

“While 50 years ago, we may not have had many Black mayors, now we have over 500 Black mayors across the United States representing over 25 million of our constituents in the cities that we serve.

We have mayors of cities both large and small, from probably as small as about 5-600 to over eight million residents in our cities,” Shawyn Patterson-Howard, former president of AAMA and mayor of Mount Vernon, New York, said at the April 24 news conference.

“Black mayors are at the forefront of so many of the conversations in America. We are critical to the economic vibrancy, to the building of equity, and to the partnerships that America needs to be a world player,” she added.

For Mayor Frank Scott Jr. of Little Rock, Arkansas, the conference was a time of reset, revival and resurrection.

“As we reset over these next few days, it helps us understand who we serve, why we were put in these positions to ensure that we’re unapologetically intentional about our residents, about our people. That’s why we were called to do what we’re doing,” he said.

“We know that times will get weary. Times will get hard, and we know that there are some ugly days ahead. And that’s the reason why we come together to stand in need of one another. Whether it’s a time of joy or a time of sorrow, you only know what another mayor knows, particularly another Black mayor.”

Life of a Black mayor

During an interview with members of the press, Mayor Patterson-Howard touched on the issues that mayors are seeing across the board. Many Black mayors have seen investments in their city’s water infrastructure and sustainability.

“My community received $200 million. I don’t want to see trucks from two counties away coming in and receiving the benefits of that funding. We want to make sure that we’re training our workforce,” she said.

She also mentioned housing affordability, building equity through home ownership and public safety.

“Being a Black mayor is amazing because no one understands a mayor like a mayor,” she said. “We can sit in the room sometimes and we don’t have to say much, because we go through very, very similar things, regardless of the size of your city. Regardless of whether you’re in a metropolitan, rural or urban community, the issues are very much the same,” she said.

“We are a brotherhood and a sisterhood who really seek to empower, uplift and strengthen one another, not just in the areas of government, but giving us the personal strength that we need to continue to do this work in an environment that is not always fair and not always friendly.”

In answering a question on challenges specific to Black mayors, Mayor Patterson-Howard said Black mayors are held to a different standard, especially in urban cities.

“Because of that, whatever happens, they expect us to be superman or superwoman as opposed to a mayor that is not Black,” she said. “You have to be at the birthday party, you have to be at the baby shower, you have to make it to every church event, but you also have to govern your city.”

“If you take vacation and there’s a shooting or there’s a flood, what are you doing out of town? People don’t expect us to have vacation time, family time, and then you’re dealing with racism,” she added. “You’re still dealing with systemic racism.”

She also explained that by the time many Black mayors get into office, their cities may have gone down so much over 30, 40, 50 years, and yet they are expected to deal with legacy issues overnight with very few resources.

In answer to a question by The Final Call, Mayor Patterson-Howard shared how Black mayors are unapologetically leading their communities with equity.

“We have to look at the neighborhoods in our community that have been disinvested in and we have to reinvest. But what we also have to get our people to understand is when we are really investing in neighborhoods that have been abandoned, that doesn’t mean gentrification always.

Sometimes we are reinvesting in our community for our community,” she said. “I believe so many of the Black mayors are really unapologetic about that. We are all working to ensure that minority and women business enterprises are getting contracts with our community.”

“We’re not providing privilege. This is not about privilege. This is about equity,” she added.

Honoring a legacy

The African American Mayors Association honored the legacy of Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor. He was elected to office 50 years ago and served as the city’s 54th mayor from 1974 to 1982. He returned as the 56th mayor, serving from 1990 to 1994.

Under his leadership, more Black police officers entered the force, more Black and women contractors participated in the city’s contracts and City Hall had more Black and women representation.

Mayor Jackson also propelled Atlanta into a thriving economic force by expanding the Hartsfield International Airport, known today as the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, which was renamed to honor Mayor Jackson.

“We really came to Atlanta because we are celebrating the 50th year of Mayor Maynard Jackson being mayor of Atlanta. And he was just such a groundbreaking leader. He wasn’t the first Black mayor, but he was the first Black mayor of a large southern city, and he served with such dignity and pride,”

Mayor Patterson-Howard said at the April 24 news conference. “He was innovative, and Atlanta is who it is today because of his economic development vision and his unapologetic and very forward-thinking leadership style.”

Mayor Wayne Messam of Miramar, Florida, also lifted up Maynard Jackson’s name.

“We chose this location because if you’re any kind of mayor, you knew about Maynard Jackson. You knew that he was the first large-scale mayor that any one of us knew. Quite frankly, he was the father of affirmative action. He, along with other civil rights leaders, are the reason why we all stand here today,” he said.

“Many of us were (the) first Black elected, first woman elected as a Black woman, we are the first. We stand on those giants, whether it was Maynard in the South or Marion in the East or Tom Bradley in the West; or even in the South, a LaToya Cantrell, in the Midwest, a Tishaura Jones and even up North, a Shawyn Patterson-Howard,” he added. “We all stand united, again, to reset, to revive, to resurrect, to do the will of our people.”

History of AAMA

The African American Mayors Association stands on the shoulders of Black mayors who decided to rebuild the organization, previously named the National Conference of Black Mayors, after the organization found itself suffering from fraud, embezzlement and debt 10 years ago.

The legacy of AAMA continues with the April 26 election of Mayor Steven Reed of Montgomery, Alabama, as president of AAMA. He assumed the role after Mayor Patterson-Howard.

In an interview with The Final Call, Johnny Ford, former mayor of Tuskegee, Alabama, founder and CEO of The World Conference of Mayors and founder of the Historic Black Towns and Settlements Alliance, explained the history of AAMA.

It started with a call in 1972 for seven Black mayors in Alabama to appear on NBC’s TODAY show.

“We met in Montgomery, Alabama, and for the first time, the nation saw seven Black mayors, the ‘Magnificent Seven’ we called ourselves, speaking as one voice. And I said once it was over, now that we’re together, why don’t we stay together?” former mayor Ford recounted. “That was the beginning of the Alabama Conference of Black Mayors.”

At the time, George Wallace was governor of Alabama. “It made sense for seven of us to deal with Wallace rather than one of us,” the former mayor said.

Fast forward to February 1973, the Black Alabama mayors had a second meeting with the Black Mississippi mayors. The mayors then formed the Southern Conference of Black Mayors and had their first meeting in December 1973 in Tuskegee.

Due to the progress being made, Black mayors in big cities voiced their desire to join, which caused the organization to expand to the National Conference of Black Mayors.

The National Conference of Black Mayors was going well until it hit rock bottom a decade ago. Mayor Ford helped then-president Kevin Johnson, former mayor of Sacramento, California, to bring the organization back to life by firing the director, filing for bankruptcy, and renaming the organization to what it is today.

“Ten years later, you now see what has taken place, but I am just so proud that I stayed with it. I’m so proud that I called that first meeting in 1972 with seven mayors. Now it has led to the African American mayors with hundreds of mayors across the country, many African American women as well as men heading major cities,” he said. “I feel like a father, a grandfather sitting back watching all of this.”

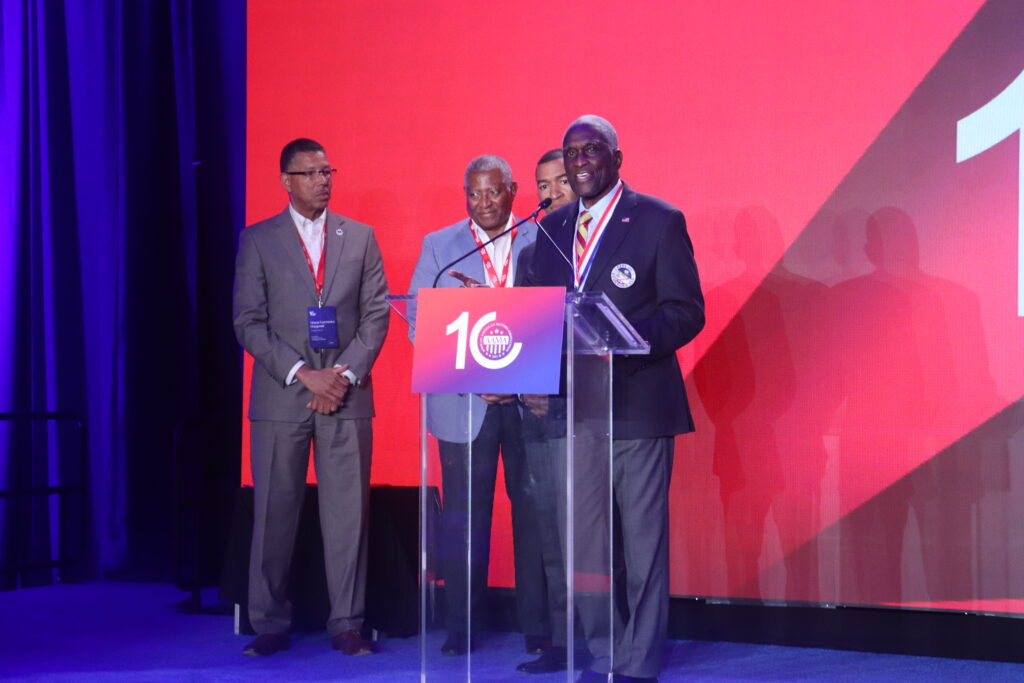

Black mayors awarded

At AAMA’s Legacy Awards Gala that took place on April 25, five awards were presented to 10 recipients.

Shirley Franklin, former mayor of Atlanta, and Wellington Webb, former mayor of Denver, Colorado, received the President’s Award for Leadership and Service.

Mayors Tishaura Jones of St. Louis, Missouri, and Wayne Messam received the Maynard Jackson Award.

“As mayors, we have a unique opportunity for a unique economic development to help to transform the lives of our Black-owned businesses and other minority-owned businesses in our community,” Mayor Messam said.

He noted the importance of Black mayors in providing legal contracts to Black businesses.

“Make sure that we are doing everything possible to ensure that our Black-owned businesses have every opportunity to not only win contracts but to grow as well, just as Maynard Jackson did right here in Atlanta, Georgia,” he said.

Destiny Daniel, a senior at Howard University, and Aria Branch of Elias Law Group received the Stephanie Mash Sykes Esquire Award for Excellence in Social Justice and Public Policy.

Former mayor Johnny Ford and Jarrod Loadholt of Ice Miller, a national law firm, received the Reginald E. Lewis Award.

“I am so proud of all of you. I don’t know what tomorrow may bring, but I have been to the mountaintop,” former mayor Ford said. “Look at you! Beautiful Black mayors from all over America.”

Shared challenges and solutions

Mayor Sonja A. Brown of Glenn Heights, Texas, won the mayoral election in November 2022. She enjoyed having the chance to network with other mayors.

“It’s really beneficial for us because we’re getting the opportunity to talk through issues, and we’re also getting to hear from some mayors who are doing things and being very successful in their cities.

And then we’re able to grab that information and take it back to our own respective cities,” she said to The Final Call. “It’s like a breath of fresh air knowing that some of the other mayors are encountering the same issues that I’m encountering and hearing from them, how they’re overcoming those challenges.”

Thurman Bartie of Port Arthur, Texas, has been attending the conference for the past few years. He described the wealth of knowledge he received from the conference.

“It brings to your city and to the constituency opportunities and information that is profitable to them,” he said to The Final Call. He enjoyed the discussions on Black generational wealth, healthcare and housing. “Things are changing. We have to be at meetings such as this to be apprised of what is going on,” he said.

Mayor Jazzmin Cobble of Stonecrest, Georgia, who also won the mayoral election in 2022, noted the importance of Black mayors getting together to discuss common challenges and common solutions.

“I think it’s also important that we get together and discuss how we as a group can help move a needle on an initiative, a strategy or a solution,” she said to The Final Call.

Mayor Errick D. Simmons of Greenville, Mississippi, has been part of AAMA for four years. He serves on the association’s board.

“The African American mayors are not only social engineers, but they’re making a difference in the lives of the people they represent,” he told The Final Call. “This group of Black leaders around the world and around the country have made it a choice to sustain their communities and impact the lives of the folks they represent.”

He described the conference as a one-stop-shop of best practices and ideas on a local level.

“How do we create equity and sustainable outcomes in our community? It’s going to be on us, and I think that’s what we’re going to do when we get back home,” he said.

Stay tuned for additional coverage from the AAMA convention in a future edition of The Final Call.