Tennessee State University in Nashville, Tenn., is one of the latest in a long list of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) under attack. Such attacks come in different shapes and forms. They look like years of underfunding, financial and accreditation problems, and political and legislative maneuvers.

Students, alumni, activists, and supporters of Tennessee State have been mobilizing after Tennessee lawmakers disbanded the historically Black college’s board of trustees and installed a new board comprised of alumni.

The move came as a result of several audits within the past year. Though auditors did not find evidence of “fraud or malfeasance by executive leadership, the University, or the TSU Foundation,” concerns around the mishandling of finances, housing and scholarships were brought to light.

Along with the dismantling of the university’s board, Tennessee State University President Glenda Glover announced that she would be stepping down in June.

Underfunding

In September 2023, the U.S. Secretaries of Education and Agriculture sent a joint letter to 16 governors—the governors of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and West Virginia—urging them to provide equitable funding for the HBCU land-grant institutions in their states.

Collectively, the HBCUs named in the letters received almost $13 billion less than their White counterparts in the same state between 1987, the earliest availability of comprehensive data, and 2020. Tennessee State University received over $2.1 billion less than the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

North Carolina A&T State University received over $2 billion less than North Carolina State University. Florida A&M University received almost $2 billion less than the University of Florida.

The 13 other HBCU land-grant institutions listed received between almost $300 million and $1.5 billion less than their White counterparts.

Only two HBCUs received equitable funding: Central State University in Ohio, which received over $23 million more than Ohio State University, and Delaware State University, which received over $366 million more than the University of Delaware.

The fight for equitable funding has resulted in lawsuits in several states. Maryland was tied up in a 15-year court battle that ended in 2021 when the state agreed to pay $577 million to its four HBCUs. Students at Florida A&M University attempted to sue the state of Florida for discriminatory underfunding, but a federal judge dismissed the case in January.

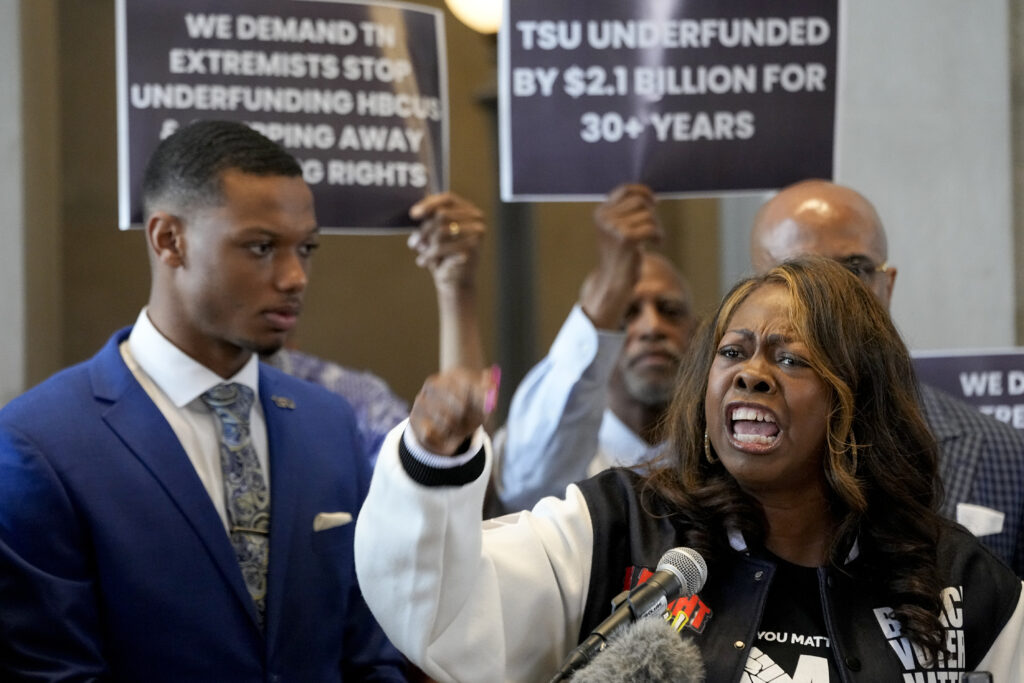

‘Stop the Attack on HBCUs’ news conference and town hall

Roland Martin, founder of Black Star Network and host of Roland Martin Unfiltered, has been covering the plight of Tennessee State for over a year. On April 1, he held a “Stop the Attack on HBCUs” National Press Conference, where students, activists and supporters voiced their dissatisfaction.

Shaun Wimberly Jr., former student trustee at Tennessee State University before the board’s dismantling, told the Black community that “now is not the time for begging.”

“It is our time to take what is ours. And I want you all to understand that. $2.1 billion here, $2.2 billion there, $1.5 billion wherever. We cannot beg anymore. They haven’t given it to us in the past, so what makes you all think they would give it to us now?” he questioned.

Mr. Wimberly is a senior agricultural business major on track to go to law school. He has stood before House and Senate subcommittees fighting for Tennessee State but felt that his voice as the student trustee was not fully valued.

Derrell Taylor, the school’s Student Government Association (SGA) president and a senior business administration major, voiced similar sentiments. “How can decisions be made regarding the university without the students?” he questioned. “You give students a position or give them the ability to have a platform and then you still take away their voice.”

He and others accused state legislators of making decisions about the university without actually stepping foot on its campus.

Rev. Dr. William Barber II, president of Repairers of the Breach, pointed out three things that need to happen: one, people need to file lawsuits against each state with an underfunded HBCU; two, the SGA president should have an automatic seat on the board of trustees and three, the reinstituting of “Black college day,” an annual day where Black colleges simultaneously march on their state legislature and demand funding.

Rev. Barber went into some of the history regarding HBCUs and funding. In 1862, the Morrill Land Grant College Act was signed into law to create colleges to “benefit the agricultural and mechanical arts,” but it left out Black students.

Twenty-eight years later, a Second Morrill Act was passed requiring states to either allow Black students to attend White institutions or to establish separate land-grant institutions for Black students. The 1890 act gave rise to the 19 HBCU land-grant institutions still in existence today.

“The whole reason we’re here is because of denial. The whole reason we’re here is because of funding,” Rev. Barber said.

“Black schools went without government land grant funding until 1970 when Congress—not the state legislature—when Congress finally passed legislation to give them an annual appropriation,” he added.

“The predominantly White schools that were land grants, they got their money from 1862 on. But HBCUs that were land grants didn’t even begin to get any kind of equity and appropriation until 1970.”

Rev. Dr. Frederick D. Haynes III, senior pastor of Friendship-West Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, and an HBCU alum, shared how HBCUs have always outperformed the limited resources they have been given.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2022, there were 99 HBCUs located in 19 states; 50 public and 49 private. According to the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), though HBCUs make up only three percent of the country’s colleges and universities, they enroll 10 percent of all Black students and produce almost 20 percent of all Black graduates. In addition, 25 percent of Black graduates with STEM degrees come from HBCUs.

“We’re saying to every state in the words of my mama, ‘Don’t steal my eyeballs and then blame me because I can’t see.’ Don’t steal from our students and then wonder why we’re not what you say, what other colleges are doing. We’re doing it anyhow,” Dr. Haynes said. “We’ve been able to see even when you stole our eyeballs. Imagine what would happen if you gave us equitable funding.”

One of the critiques of Tennessee State was inadequate housing compared to the number of students enrolling. According to an August 2023 article by Tennessee Lookout, “TSU’s 2022-23 freshmen class saw about a 1,600-student increase, putting the university in a housing emergency and forcing officials to request the use of local hotels and a church to provide dorms.

The university received approval but irked state lawmakers, who said Glover and the board could be removed for pushing scholarship and enrollment increase without having enough housing.”

At the news conference, Tennessee State supporters questioned why the college is being punished for accepting too many students.

“Why does TSU have to go back to the legislature? Because they did not have $2.1 billion, and they had to go back to ask them for resources for the hotel. Perhaps they could’ve purchased a hotel as well if they had gotten $2.1 billion,” LaTosha Brown, co-founder of Black Voters Matter, said.

“Perhaps some of the money that was meant for this university actually got allocated to that university,” she added, referring to the University of Tennessee.

Roland Martin hosted a town hall meeting hours after the press conference. Speakers at the town hall discussed how across the country where HBCUs were established, White institutions would pop up and duplicate what HBCUs were already doing.

These White institutions would then reap the benefits of government funding while Black institutions were left neglected. Speakers shared that state and local governments had a problem with the quality education HBCUs were providing to primarily Black students.

Tariq Muhammad, a Tennessee State alum, referenced words from the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam from a 2012 visit to the school.

“The Minister stated that the enemy wants the land of TSU, … and I’m sure it’s the same case for our HBCUs nationwide. Tennessee State University sits on 500 acres of prime real estate. That’s strategically important for the enemy’s plans,” he said to The Final Call. “If they don’t want that land, they want to control what’s being said to the students that are coming there. The enemy doesn’t want our people to learn about the science of business, the science of land or agriculture.”

Tequila Johnson, co-founder and CEO of The Equity Alliance, is a two-time graduate of Tennessee State. She started her advocacy for the university as a sophomore student. Now, she works through her organization to hold state and local leaders accountable.

She shared with The Final Call that part of the attacks against HBCUs is due to the migration of people moving back to the South, causing intentional, rapid gentrification. HBCUs sit in those same areas and lie on huge tracts of land.

“A lot of this underfunding is leading to hostile takeovers of the land that our HBCUs in some of these confederate states are sitting on, especially a school like Tennessee State University that is in one of the most rapidly growing areas of Nashville,” Ms. Johnson said. “There are so many talks of how to develop that land.”

“I think it’s important to note that while we’re sitting on all of this land, and our state legislature has shown us that at any moment, they can come and take over that board, we need to not only hold our state accountable because it’s the right thing to do, but we also need to hold them accountable to make sure those TSU alumni that we put on that board are protected,” she added.

Bias in accreditation

Other HBCUs currently facing challenges include Saint Augustine’s University in Raleigh, N.C., Barber-Scotia College in Concord, N.C., and Cheyney University in Cheyney, Pa.

Saint Augustine’s University lost accreditation through the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) in December and is now going through a 90-day arbitration process.

Cheyney University, the oldest HBCU in the country, was placed on probation in November by the accreditor Middle States Commission on Higher Education.

HBCU accreditation is important due to the majority of HBCU undergraduate students receiving federal financial aid. Morris Brown College in Atlanta lost its accreditation in 2002 and did not receive full accreditation again until 2022, after cleaning up financial issues and reapplying through the Transnational Association of Christian Colleges and Schools (TRACS).

In 2023, Bennett College was awarded accreditation by TRACS. Both schools were previously accredited under SACSCOC.

HBCUs have a painful history with SACSCOC. The UNCF’s Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute published a research paper titled, “Biases in Quality Assurance,” tackling the subject.

“The relationship between HBCUs and their primary accreditor, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC), has been fraught with undulating degrees of difficulty since HBCUs initially sought membership prior to WWII. The increasing rate of sanctions in recent years has been cause for alarm within the sector and should be a matter of concern for all higher education … ” the paper states.

It cites a research study that found that minority-serving institutions, including HBCUs, tend to receive harsher sanctions than other institutions and that negative media coverage reinforces stereotypes about HBCUs, which limits access to funding and other support.

“Therefore, the negative actions disproportionately handed down by SACSCOC to HBCUs often compromise the very institutional quality they are charged with assuring,” the paper says.

It lists four grievances HBCUs have with their primary accreditor: uncertainty in the peer review process, lack of transparency regarding why institutions are sanctioned, lack of exposure to the accreditor’s evaluation and using the same evaluation criteria for small, historically underfunded HBCUs and for large, wealthy and predominately White public institutions.

“Institutions with missions to serve underserved students and communities, which often have minimal resources and reflect the communities they serve, are not well-represented in the standards,” the paper states.

Barber-Scotia College lost its accreditation in 2004 from SACSCOC, but its current president, Chris Rey, who was appointed about eight months ago, is attempting to regain accreditation by 2026. He said to The Final Call that he plans to put together a strong team to help the college meet the standards for reaccreditation through TRACS.

He traced HBCU accreditation issues to the lack of resources, causing staff to do double or triple their role.

“If you have an individual who’s doing two or three jobs, that means somewhere along the line … they’re going to drop the ball on some part of their responsibility,” and the accrediting process might be part of that ball, he said.

Uniting and doing for self

At the recent news conference and town hall, supporters of Tennessee State dialogued about a possible lawsuit. They shared that while the school itself cannot sue Tennessee, other parties such as alumni can sue.

Ms. Johnson emphasized the need to build a strong coalition of people around the HBCU fight, to organize under a national platform, and to allow HBCU students to be at the forefront of the ongoing movements.

Mr. Rey shared the importance of working together in the face of the coordinated attack against HBCUs. “One of the things we have to do as institutions is really work together to see how we can pool our resources together so that the institutions can continue to thrive, but at the same time, continue to find creative ways for us to exist and to coexist,” he said. “All the HBCUs need to be working together because we matter.”