Between 1964–1975, more than 2.7 million American servicemembers served in the Vietnam War, including more than 300,000 Black soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines and Coast Guardsmen. Yet, their individual testimonies have often been overlooked by history.

One such story is that of a young U.S. Army Green Beret separated from his pregnant Vietnamese girlfriend after the withdrawal of American combat troops nearly two years before the April 30, 1975, fall of Saigon, the capitol city of what was once South Vietnam.

Willie James Henderson, 75, told The Final Call that he was drafted into the U.S. Army after graduating high school in 1969 and that he attended basic training at Fort Dix, New Jersey. Upon completion, Mr. Henderson described how an Army Special Forces (Green Beret) recruiter approached him after completing Advanced Individual Training (AIT) as a medic at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas.

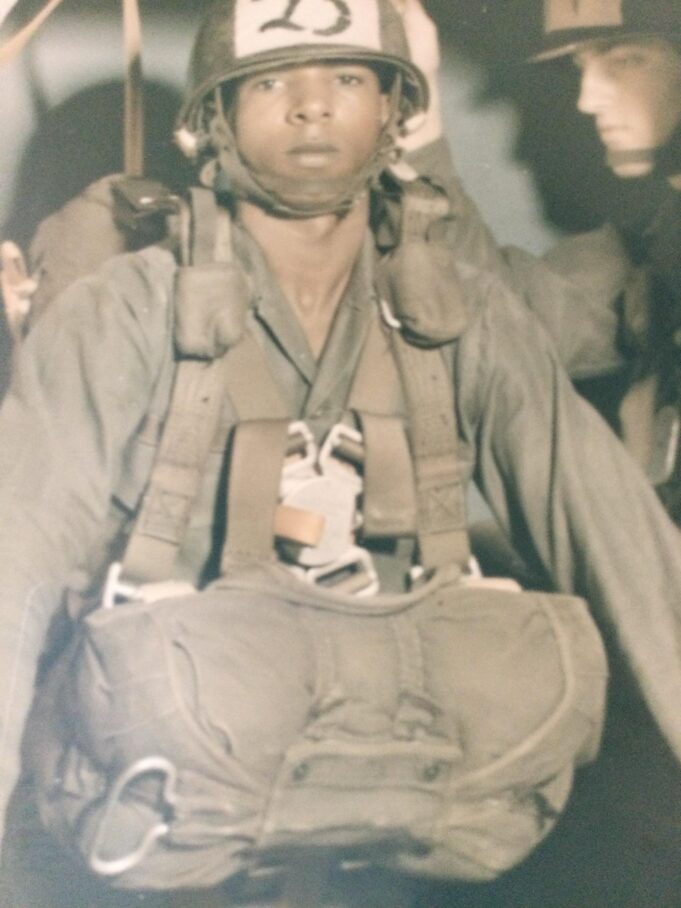

“He recruited me into Special Forces and then I had to go to jump school (parachute training) at Fort Benning, Georgia, got jump qualified, and then I went to Fort Bragg for Special Forces training,” Mr. Henderson said. He also said that he received additional instruction as a Special Forces communications specialist while stationed there.

“I went to Vietnam in the beginning of ’70, and a tour in Special Forces was six months. I was there for 18 months (three tours),” Mr. Henderson said. “I was first stationed on top of a mountain called Núi Bà Đen (the Black Virgin Mountain).”

During the war, then Sergeant Henderson described the nature of being assigned to an “A-Team” within the 5th Special Forces Group. An ‘A-Team’ is the primary fighting force within Special Operations that work in small units to sabotage enemy communications and supply-lines and to infiltrate enemy forces using guerrilla war-style tactics.

Later garrisoned at a base camp in Tȃy Nihn, it was there that then Sergeant Henderson met his girlfriend, Bạch Thị Dương, a Vietnamese national and civilian, who worked at the base. Describing the subsequent withdrawal of U.S. forces near the end of the war as chaotic, he received orders sending him and other members of his unit back to the United States.

“I fought those orders, I went through the chain of command and explained my situation and said my girlfriend is pregnant, and I said I wanted to stay here and wanted a six-month extension, and they wouldn’t give it to me,” Mr. Henderson painfully recalled. “I went all the way up the chain of command to a general and he said, ‘I can’t help you; they’re sending me home too,’ so, I had to come back to the states,” he continued.

“I wanted to go back to Vietnam and they wouldn’t send me,” Mr. Henderson said of the immediate aftermath of the troop pull-out and the inability of the U.S. government to intercede in individual cases such as his. “And then the war was over in ’75,” he said.

‘Back in the world’

Mr. Henderson is originally from Hartford, Connecticut, but when he returned from the war, the city had changed, he explained. “When I left Hartford, (it) was a beautiful city, but when I came back, they had a lot of change. They were not the people I had left and I stayed there about six years. And in 1978, I couldn’t take it anymore.” Changes included children as young as 12 carrying guns and gang activities.

These changes prompted Mr. Henderson to reenlist in the military. After taking a friend to a Marine Corps recruiter, Mr. Henderson said it was there that he decided to reenlist after an Army recruiter reviewed his discharge papers and convinced him to return. He agreed, but only if he could get a military occupational specialty (MOS) other than the combat arms field.

“He said I could pick my own MOS, so I picked 75 Delta which at that time was a personnel records clerk, because I got tired of all that combat s—t. So he (recruiter) said we will send you to Fort Jackson (South Carolina). I went to that school, graduated, and got sent back to Fort Bragg,” he said.

However, there is a difference between what a recruiter says and what actually happens “when you sign the dotted line,” Mr. Henderson said. He was once again assigned to a Special Forces A-Team, “for the good of the Army,” and then reassigned to the 2nd Infantry Division at Camp Casey in South Korea after his chain-of-command finally agreed he was to be a personnel clerk.

“I got a letter from Bạch and she had a picture in it of her holding the baby (my daughter), but it was sent to Hartford, Connecticut, so what could I do?” Mr. Henderson asked.

The United States did not reestablish diplomatic ties with Vietnam until 1995 and Mr. Henderson said he could not return there even after receiving word of the letter. It would take him 50 years to speak with his daughter for the first time, albeit through FaceTime on their cell phones.

An arduous journey

According to a March 14, 2023, USA Today article by Nguyen Phan Que Mai, an estimated “100,000 Amerasians were born during the war from relationships between Vietnamese women and U.S. soldiers.”

Separated by war, distance, and time, it was unlikely that many of these children would learn their full identities as persons born of two vastly different worlds, travel to the United States, and find their biological fathers upon arriving.

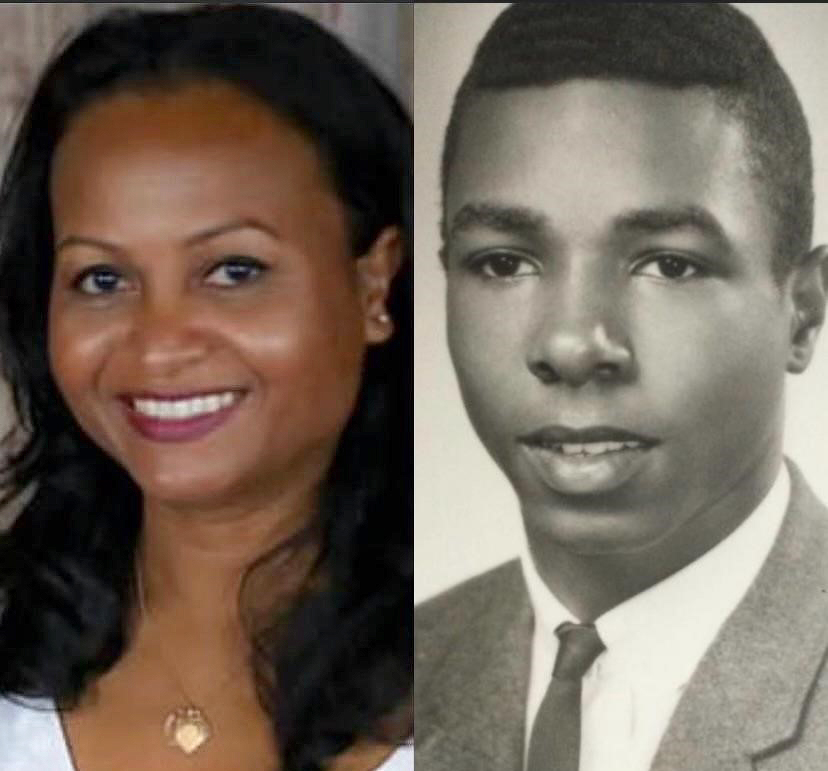

Diane Dương, 52, was born Dung Thị Dương in the town of Thê Ba near the Cambodian border almost four years before North Vietnam’s 1975 takeover of the entire country.

Now living in Texas and working as a schoolteacher, she shared with The Final Call her story of growing up in Vietnam as a Black Amerasian, and the harrowing journey that she, her mother, and her baby sister endured while fleeing the country in the hopes of finding her father.

“I pretty much remember from the time I was five or six years old, where a lot of my time was spent with my grandma who raised me,” Ms. Dương said. “Our morning routine consisted of going to pick mangos, and we would take (them) to the market to sell and whatever money we made, I would take it to buy soup (and) I would always be the first customer around 5:00 a.m. and then be on my way to school. I didn’t know about the war when I was growing up; I didn’t even know the war even existed,” she said.

But coming of age as the child of an American soldier in Vietnam, particularly a Black American soldier, was difficult and not without frequent taunts by others, including other children. Experiencing racist discrimination and being ostracized as one not truly belonging, Ms. Dương described how young people would sing songs toward anyone who was mixed from American soldiers, whether Black or White.

“They would sing it out loud to taunt us. If you asked any Amerasian child today, they can all tell you, it was the same song and you would hear it over and over again,” Ms. Dương explained. “On my way to school, anywhere I would go in public, that song, they would sing it, and of course the stares and being looked at and they would whisper things among themselves, so that, I experienced growing up in Vietnam.”

Ms. Dương said the same taunts and criticisms were also cast against the mothers who had children from American soldiers. “It was more about ethnicity and the color of a person from when the American soldiers were there, and in my home town or in other towns (nearby) it was always the same thing, Vietnamese parents telling their kids, ‘Oh, don’t stay out in the sun for too long, you’re going to get dark’ and ‘Black is ugly,’

Or ‘get inside, you don’t want to get dark,’” she said. Ms. Dương shared that even to this day when she visits Vietnam, women put on heavy foundation to look lighter skinned or more White.

Eventually leaving Vietnam with only the clothes on their backs, Ms. Dương said that by the age of eight, she and her mother struck out on foot after she was put out of school while her mother and grandmother endured the hardship of extreme poverty. Often depending on the kindness of strangers for food and transportation, Ms. Dương and her mother walked across the border into Cambodia while also carrying her 11-month-old sister.

They eventually made it to a refugee camp in Thailand after months of sleeping in fields, taking shelter in abandoned buildings, enduring the dangers of wild animals, and avoiding opportunists seeking to take advantage of their plight.

“My mom had the picture of my dad and the back of that picture had his name, his address, his birthdate and everything,” Ms. Dương said, recalling how her mother later buried it after being detained by border guards because they were trying to pass as Cambodians visiting relatives.

“My mom got scared because if they (found) this picture, for sure they were going to send us back to Vietnam, so she buried it.” They would eventually walk over 700 miles arriving in Thailand in the early 1980s.

In a January 14, 1983, Washington Post story, William Branigin wrote that the Thai government agreed to allow the United States and other countries to begin processing Vietnamese refugees within their borders. “Among the 1,890 detainees at the overcrowded camp, called NW82, are five Amerasian children fathered by Americans during the Vietnam War, U.S. officials said.”

with her grandmother, around 1978.

“Known as ‘land people’ to distinguish them from the ‘boat people,’ the Vietnamese reached the Thai border by making a hazardous overland trip across embattled Cambodia,” The Post article said. This was in the wake of the 1976-1978 Cambodian genocide carried out by the Khmer Rouge government of Pol Pot where up to three million Cambodians were brutally killed.

Finding her father

Ms. Dương told The Final Call that it was the late Congressman Rep. Harold Sawyer (R-Mich.), who helped to move her, her mother, and baby sister to the United States by way of Thailand through another refugee camp in the Philippines, before coming to America.

They arrived in Michigan in the mid-1980s, and with the help of the local Vietnamese community, sponsors, and a Black family in Grand Rapids, she learned English, completed a Master of Education, and began working as a schoolteacher.

It was with the help of Kristee Mays, of “Kristee–Genetic Genealogist,” an advocate who has helped more than 200 Amerasian clients to find their biological fathers over the last six years, and anyone seeking out a birthparent—including adoptees, abandoned babies, and others born from unknown fathers—that Diane Dương was finally able to locate her father in 2021.

“So many more Amerasian people are searching for their American fathers,” Ms. Mays told The Final Call via email. “They have wondered their whole lives and would love to know what he looks like, does he have other children, what is their medical history and who are their ancestors? Everyone deserves to know their story whether it is painful or not. It’s their story,” she said.

“All these years of my life, my mom had spoken very positive about my dad, like he was kind, he was nice, he’s tall, he’s handsome, so it made me want to know, and for me, it was like a big closure,” Ms. Dương said of the day they finally made contact. “Knowing that he’s alive and OK, my biggest goal now is how can we meet in person and go from there.”

Both she and her father Mr. Henderson, who is disabled and currently living on the East Coast, plan to meet face-to-face in the near future.

The injustices of circumstance such as war, create longing, pain, and sorrow, that for many continues long after headlines fade and the effect of war lingers. Regarding the need for resolution, whether it be international, national, or local, there is a need in the human being for freedom, justice, and equality.

On February 22, 2015, during the Nation of Islam’s annual Saviours’ Day convention, the National Representative of the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, said at Christ Universal Temple in Chicago, that the temporal solutions of man are inadequate to solve the people’s yearning for what is natural and just.

“No change can satisfy the demand of the human family for justice,” Minister Farrakhan said in his keynote address: “The Intensifying Universal Cry for Justice.”

“No change orchestrated by those presently in power could ever satisfy the cry of the people. Do you know why? Because this cry is not a cry that comes out of some petty hurt or pain, it’s not a cry to fix the unions, it’s not a cry to straighten out the politics, it’s not a cry to get the mosque right or the church right, it’s so much deeper than that,” the Minister said.

“The change that will satisfy the cry of humanity can only come, not from any present ruler, but from God himself … the people are crying out for the Kingdom of God to be established on the earth,” Minister Farrakhan said. “There’ll be a new sun, a new moon, and a new star, but that’s not what scripture is talking about.

A new heaven means a new spiritual order and a new political order governed by the spiritual order, that will bring human beings together, not on the basis of color of skin or ethnicity or biology, but on the basis of our desire to do that which is right,” he said. Read part 1 of “Black veterans tell their stories,” in The Final Call, Vol. 43 No. 11.