As the likelihood of America entering into another war increases, from Eastern Europe to the Middle East, and possibly into the Far East, a cross-section of Black veterans recently shared their unique perspectives regarding their times in the military, their struggles upon separation from the armed forces, and the lessons they learned in many cases overlooked by a society increasingly distracted, dissatisfied, and divided along the lines of creed, class, or color.

Mr. James Todd Jr., 75, enlisted in the U.S. Army and served from 1968 to 1970. He told The Final Call that volunteering with a choice and a chance to serve elsewhere was better than being drafted without a choice and being sent to Vietnam. After attending boot camp and completing his advanced individual training at Fort Knox, Kentucky, Mr. Todd received orders for the Third Armored Division in Gelnhausen, West Germany, as an armor intelligence specialist.

“I was in Company A, 1st of the 33rd Armor,” Mr. Todd said. “I was young. I was 18 when I went in and I grew up there with a bunch of guys from all over the United States. I made a lot of good friends. Some of the bad things was going out into the field, in the cold, drilling because our responsibility was to protect the Fulda Gap, if the Russians should attack and try to invade into West Germany,” he explained.

The Fulda Gap was a strategic and heavily defended entry point between East and West Germany during the height of the Cold War. “When I was there, in ’68, the Russians invaded Czechoslovakia, and that was kind of a harrowing experience, to wake up at 3:30 – 4:00 in the morning (and) being ready to take your tank to the Fulda Gap where you would defend Germany,” Mr. Todd said.

“When (the Russians) invaded Czechoslovakia, that was not an (exercise), but thankfully they stopped and didn’t keep coming because they had given us something of a life expectancy of 25 minutes if we had to fight. We would have been outgunned and outmanned 20 to one,” he explained.

“When I joined, there were eight or nine of us from Muskegon, Michigan, that joined at the same time and went through Fort Knox together. At one point we were all students at Muskegon Community College and a lot of us felt we were going to get drafted, so we might as well sign up in order to get a better (military) job and that happened,” Mr. Todd explained.

“Out of the nine that left out of Muskegon in April of ’68, one of us went to Vietnam. I did interact with a few guys (who went to Vietnam), and one came back really whacked out; I don’t know if it was drugs or what, but he really wasn’t the same person (after) coming back.”

‘A living hell’

Mr. Quintan Cooley,75, was an Army draftee, born and raised in New Orleans. He voluntarily extended his tour of duty by an additional six months after a friend was killed in combat. He told The Final Call that he was assigned to MAC-V headquarters(Military Assistance Command—Vietnam) in 1967 as a communications specialist at the Lê Văn Duyệt compound in Saigon, and likened his in-country experiences to a living hell.

“I got out a long time ago, when I needed to, and went through a lot of changes and had thought no more about it since, other than that I served,” Mr. Cooley said of his time in Vietnam, where he worked in reconnaissance and intelligence operations with 5th Special Forces Group, the 173rd Airborne Brigade, Army Rangers, and the U.S. Navy’s river patrol squadrons.

“When I went in, it was crazy. The war wasn’t for a Black man. Some brothers stayed in, but for me it was hell and I went through hell, and I needed to get out to reassess myself to see where I was going in life,” Mr. Cooley explained. “I was young. I did a lot of growing up. I met a lot of brothers from the South who had legitimate issues (and) I witnessed a lot.

When I went in, Black brothers didn’t have a lot to choose from, it was chosen for us. I met a lot of brothers, a lot of combat brothers,” he said of the various things he witnessed both in and out of the field.

“We took tests, (which) set me apart. I found myself being the only Black in my communications school. Brothers were basically looked at as combat soldiers. If you took tests and passed the tests in other fields, other than combat, you were looked upon as an exemplary cat,” Mr. Cooley said of the various selection processes that would eventually place him in the Army’s “G-2 section” at MAC-V headquarters. G-2 refers to the military intelligence staff at the divisional level and above.

“When I came home, the VA (Veterans Administration) was totally different. It wasn’t for us and wasn’t there for a lot of us,” Mr. Cooley said of his returning stateside at the end of his enlistment in 1971. “This country was ill-prepared for (that) war, (and) there were so many things I brought back from the war with me, and I lived it for years and I rebelled from the White world because you’re not going to run this on me,” he said.

“I came back very, very militant, real militant, and I’m glad I was militant because I came back impatient with what they were telling me,” he said. “I walked a different path. I wanted to be independent.”

Black women who served

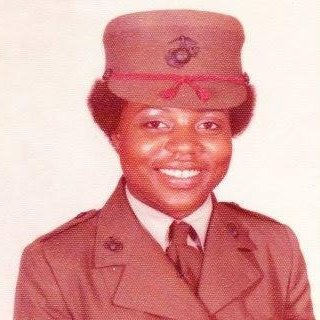

Among Black veterans, the contributions, sacrifices, and unique perspectives of female service members are often overlooked, requiring trailblazers to set standards of military life above and beyond the stereotypes, prejudices, and restrictions unique to military women in general, and Black military women in particular.

Attorney Paula Tillman, 68, served in the United States Marine Corps as a military police officer from 1976 to 1978 and told The Final Call that since her sophomore year in high school, becoming a lawyer had been her greatest desire, but she found the cost of pursuing a law degree prohibitive.

“I wanted to be an attorney, but my only option to pay for my education (was) educational benefits from the military,” Ms. Tillman said. “My brother had (gone) into the Marines in ’66 and educated me about the Marines. They were the toughest for a woman to get in and the toughest intellectually and physically for anybody to make it, so I chose the Marine Corps,” she said. She didn’t go in after high school in 1973 because the Marine Corps’ military police specialty wasn’t open to women until 1975.

“So, I served among the first female MPs in the Marine Corps, (and) all women went through Parris Island,” Ms. Tillman said of her entry as a recruit there before leaving to learn her MOS (military occupational specialty). “I had to wait for my orders after I enlisted because they only took 50 women a month from the whole United States, (and) I spent my time getting ready. But it still was challenging. It still challenged me mentally and physically and because I was the only one going to military police school,” she said.

“I had more problems as a woman than as a Black person,” Ms. Tillman said of her permanent party assignment at Marine Corps Base Quantico near Triangle, Virginia. “In terms of the White boys I had to work with, they knew better (regarding) racism, but they challenged me as a woman because I was the only woman in the platoon, and growing up the way I did, you know the difference between discrimination because you’re Black and discrimination because you’re a woman,” she said. Ms. Tillman added that her duties included enforcing all military and civilian law on the base.

Now she is a retired lawyer in Muskegon, Michigan, and an advocate for veterans in general. She is also an outspoken advocate for active military personnel and veterans who are survivors of MST (military sexual trauma), and filing claims for assistance and benefits.

Ms. Tillman also explained that during her two years in the Marine Corps, she suffered from chemical exposure while at training with the Army at Fort McClellan, Alabama, and has since received disability compensation through the PACT Act through the Department of Veterans Affairs. “If it came down to them giving me my health back, they can take those benefits,” she said. “But I know of a lot of people who are carrying a lot of problems and have been struggling for years trying to get the benefits they deserve.”

According to a recent news report from nbcnews.com, data compiled by the VA shows that Black veterans are denied VA health benefits more often than White veterans. “In fiscal year 2023, 84.8 percent of all Black veterans who applied for physical or mental health benefits were given assistance by the VA, compared to 89.4 percent of their White counterparts who applied.

The VA data includes information dating back to fiscal year 2017, which shows that White veterans have had a higher grant rate than their Black counterparts every year,” the network reported in June 2023. According to the nbcnews.com, the VA launched a new Agency Equity Team to try to figure out why health and other benefits are doled out at different rates and whether the VA can level the playing field for Blacks, women and LGBTQ+ veterans.

The network also reported that according to 2017 data, Black veterans were denied disability benefits for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at higher rates than their White counterparts and that while new data shows that from the fiscal year 2017 to 2023 that trend decreased slightly, but a higher percentage of Black vets are still denied PTSD benefits more than White vets.

Get knowledge to benefit yourself

Dr. Wayne T. Muhammad, a member of the Nation of Islam’s Muhammad Mosque No. 93 in Macon, Georgia, told The Final Call that prior to accepting Islam, he joined the Army as a means of taking charge of his life and to provide for his child as an example of a responsible young father.

“I was raised without a father, and I was determined to be a good father for my young child at age 17,” Dr. Muhammad said. “In the ’80s, I was able to switch service, so after 18 months in the Army, I transferred to the Navy and I had to go through boot camp again. I was active duty Navy for nine years and six months, there was a vast difference between the Army and the Navy,” he said.

Training to become an electrician’s mate at Naval Station Great Lakes in North Chicago, Illinois, Dr. Muhammad served on the USS Fulton in Groton, Connecticut, from 1988 to 1991 until the ship was decommissioned. He later flew to Bahrain in the Persian Gulf to meet the USS Yosemite to which he was assigned during Operation Desert Storm.

“As a repair electrician, once we got over, we went to port and we had reports that other ships needed electrical work done. We would get on helicopters and they would fly us to those ships out at sea or they would pull up on a different pier in that area or around the Red Sea and would go there and conduct the repairs and then fly back to our ship,” he said.

Dr. Muhammad said he eventually suffered stressors and other service-connected maladies related to his Gulf War service that still affects him to this day and received an honorable discharge in 1996 after completing his time on shore duty in New London, Connecticut. “Being in the Navy and being married is very difficult when you’re out for six or seven months, and then you’re back at sea and then trying to maintain a relationship is very difficult,” he insisted.

Dr. Muhammad said his advice to young Black people who are thinking of entering military service is to understand that to be accepted, a young man or woman must learn to submit to a culture and a mindset with which they may not agree and to accept the consequences for failing to do so.

“If you adapt to their way of life, you can succeed in the military, but if you want to continue being a strong Black man standing up for what you think is right, you’re going to be outcast and that’s a dangerous thing regardless of what branch of the military you’re in,” he said.

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, the National Representative of the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad of the Nation of Islam, has spoken of the sacrifices Blacks in the U.S. military have made on behalf of their country only to be mistreated or overlooked when they return home. He has warned young Black, Brown and poor White youth, that America will use them to fight in wars overseas.

Blacks fought in the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, Civil War, Spanish-American War, both World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam, the Minister explained in his article titled, “A Case For Reparations: Add It Up!” originally published in The Final Call newspaper, Vol. 1 No. 4. What he wrote then is just as applicable as the U.S. engaged in several wars and conflicts since then.

“We left our fathers on Normandy Beach, in Palermo, in Rome, in Naples, in Sicily. We left our bodies on the streets of Paris, in Belgium. Add it up. We joined the war. They used us in Hawaii, in Bataan, in Corregidor, in the Solomon Islands, in Iwo Jima. We lost our lives fighting for America. And after the war was over, America rebuilt Germany. Now the West German economy is the strongest in all Europe.

We rebuilt Japan. Now the Japanese are world leaders, but Black people who helped you win the war, they are homeless in Atlanta, homeless in Chicago, homeless in Detroit, homeless in Boston, in the streets looking for a job, looking for a handout. We helped you to win, but you offered us nothing. I say, add it up. Add it up. Add it up!” Minister Farrakhan wrote.

For any veteran seeking medical or mental health services including PTSD, MST or needs information regarding benefits including the PACT Act, call 1-800-827-1000, visit your nearest Vet Center or visit www.va.gov.