The U.S. holiday called “Thanksgiving” looms near as Indigenous Natives in America prepare for the 54th Annual National Day of Mourning amid challenges across various demographics.

At noon on November 23, at Cole’s Hill (above Plymouth Rock), Plymouth, Massachusetts, Indigenous people and their allies will gather to commemorate a National Day of Mourning on the U.S. Thanksgiving holiday as they have since 1970, according to UAINE (United American Indians of New England).

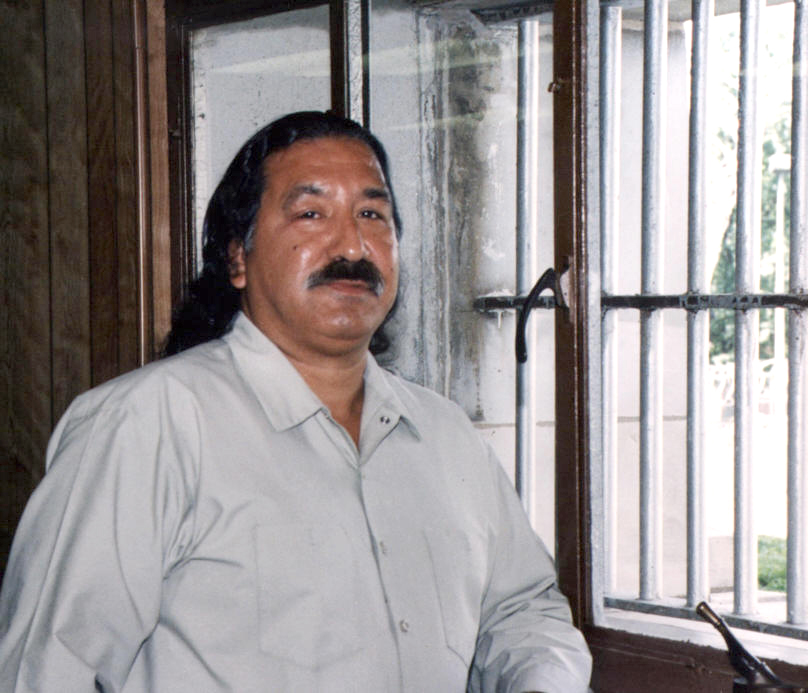

UAINE is a Native-led organization of Native people and their supporters who fight back on such issues as the racism and the U.S. government’s assault on poor people. The organization also fights for the freedom of Leonard Peltier and other political prisoners.

Mr. Peltier, a 79-year-old Nobel Peace Prize nominee, is serving life in prison for the shooting of two FBI agents during an altercation on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in 1975. For decades he and his supporters have argued he was wrongly convicted. Efforts to get various U.S. presidents to grant him clemency have been unsuccessful.

“Many Native people do not celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims and other European settlers. Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of Native people, the theft of Native lands and the erasure of Native cultures,” indicates UAINE on its website.

“Participants in National Day of Mourning honor Indigenous ancestors and Native resilience. It is a day of remembrance and spiritual connection, as well as a protest against the racism and oppression that Indigenous people continue to experience worldwide,” it continued.

In “Message to the Black Man in America,” the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad wrote, “The White man came out of Europe in desperation seeking a place to expand and began to kill the aboriginals of this continent (the Red Indian) and take their homes.

This was one of her great sins. The White man has left a remnant of that people for the sake of mockery and for his children to see the people their fathers conquered in taking this land of the Indians for their own land (as they call it today).”

In 2015 Messenger Muhammad’s National Representative, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, addressed Native youth at the UNITY (United National Indian Tribal Youth) gathering in Washington, D.C.

The Minister talked about the value, deep history and longtime oppression of the Indigenous people of America and the need for Native American youth to embrace and pursue a deep understanding of who they are to reclaim their land, restore the Red Nation and create a future for themselves and their people.

While many supporters will attend the National Day of Mourning in person, organizers also plan to livestream the event from Plymouth at uaine.org.

“We’re always seeking recognition. Many times, we’ve been written out of history despite being the original people of the land, so there’s many things that we find ourselves struggling on a day-to-day basis,” stated community activist and advocate, Hector Perez Pacheco, a Quechua from the Confederations of Tawantisuyu.

He acknowledged that Natives have been successful in making strides in some areas but have a lot more to work toward. Simultaneously they struggle to continue to exist, he told The Final Call.

“What this country has done very well is assimilation. They’ve worked on assimilating our people and our cultures and our heritage, while we as Indigenous people, we have great honor and respect for who we are,” stated Mr. Pacheco. As caretakers of the land, they have responsibilities from the Creator which also involve taking care of those ceremonies, prayers, values, and traditions of their ancestors and people, he said.

Some have worked on economic development, while a major portion of their people are still struggling, according to Mr. Pacheco.

For example, according to the Economic Policy Institute, today, tribal governments have collectively scaled a $34.6 billion industry (gaming industry revenues and related enterprises and amenities) and become a distinctively important component of the U.S. economy (National Indian Gaming Commission 2020).

Their path to economic revitalization is singularly unique and demonstrates the remarkable power of self-determination to overcome adversity and change adversarial systems, according to Patrice Kunesh, author of the June 15, 2022, report, “The power of self-determination in building sustainable economies in Indian Country.”

Ms. Kunesh also reported that “Today’s economic successes show the potential and resilience of Native Americans, who are still working to overcome generations of wrenching geographic displacement and oppressive bureaucratic supervision.

The high levels of persistent poverty, chronic health problems, and substandard housing for many Native Americans are current manifestations of economic and cultural shocks that deprived Native Americans of their livelihoods and social infrastructure and the deliberate decimation of the North American bison and the assimilation of Indian children via forced placement in residential schools are prominent examples.”

“When they (colonizers) came to this land, we were economically driven and we were self-sufficient. We didn’t rely on no one,” stated Mr. Pacheco. “Due to them coming to our land, we have found ourselves in a different framework and a different mindset and so it’s important for us to work towards becoming as we were in the beginning, self-sufficient,” he said.

In addition to trying to overcome that struggle, each demographic of their people is grappling with specific challenges, according to Mr. Pacheco. One challenge is for people to understand that Indigenous people have their philosophies, principles, and values, and that’s what makes them who they are, not the color of their skin, he continued.

He explained the four laws of his tribe are to not lie, or in other words, “be a person of your word.” The second is to not steal. “If we stole, they would cut our hands off, but it’s the opposite, it’s to give of ourselves, of who we are, to be of service, to put 150 percent behind anything that we do,” he said.

The third is to not be lazy, but the opposite of that is to be productive, and strategic, Mr. Pacheco explained. “We know we come from the Star Nation to this reality. We’re here to make a difference, so that means that we’re seeking guidance and wisdom from others so that we make the biggest difference that we can.”

The fourth law of his tribe is not to gossip, and if one does, they are shunned, he said. “Our words that come out of our mouths are words of kindness, direction, intelligence, not of foolishness. So we have to be positive in mind, in spirit, and our words are meaningful, are utilized to uplift, not destroy,” he elaborated.

According to Mr. Pacheco, every tribe has its principles and values, passed down since the beginning of time from their ancestors, generation to generation. However, a lot of Native people are losing track of these principles and are adopting other destructive ways of thinking that lead to alcoholism, self-destruction, self-medicating, drugs and other things that are negative, he stated.

For their part, Native and Indigenous youth are pushing for change and reclaiming their heritage and culture, in efforts to heal from decades of White colonization and its ongoing effects. One example is the Center for Native American Youth, which noted that as of the 2010 U.S. Census, there are over five million Native/Indigenous people, making up approximately two percent of the U.S. population. Over two million are under the age of 24. There are currently 573 federally recognized tribes.

Created to raise awareness for and prevent teen suicide in Indian Country, the Center for Native American Youth indicates that Native American communities experience higher rates of suicide than any other ethnic group. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for Native American youth ages 10-24, and Native youth teen suicide rates are nearly 3.5 times higher than the national average, according to its data on Teen Prevention Suicide.

Part of the organization’s effort to reduce Native youth and teen suicide and to empower youth to be leaders in their communities includes community-based recognition programs, a national Champions for Change Program, art competitions, fellowships, civic engagement training and/or other opportunities for Native youth.

As for their elders, the challenge is Type 2 Diabetes (one’s cells don’t respond normally to insulin), said Mr. Pacheco. According to the Office of Minority Health, American Indian/Alaska Native adults are almost three times more likely than non-Hispanic White adults to be diagnosed with diabetes.

In 2018, they were 2.3 times more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to die from diabetes, and in 2017, they were twice as likely to be diagnosed with end-stage renal disease than non-Hispanic Whites. The risk factors cited are obesity and overweight, hypertension, high cholesterol, and cigarette smoking.

Native activists and advocates urge for the continued and increased Congressional support of the $150 million funded Special Diabetes Program for Indians, which was set to expire on September 30. According to a September 14 action alert by the National Council of Urban Indian Health, currently, 31 urban Indian organizations receive such funding that enables them to provide necessary services that reduce the incidence of diabetes-related illness among urban Indian communities.

“We need to go back to the original foods of our ancestors, that is, vegetables, grains that are healthy,” encouraged Mr. Pacheco. Our people used to live to 130, 150 or 160. One of our elders passed away. She was 112,” he said.

In terms of Indigenous women and girls, many have gone missing, just as with first contact with the Spanish in the beginning, stated Mr. Pacheco.

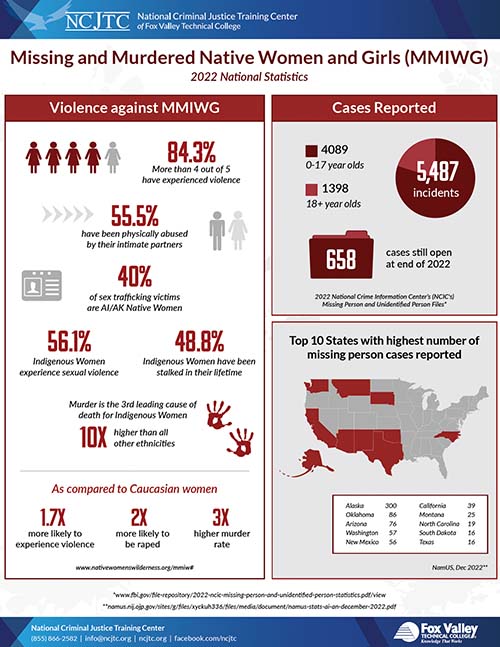

According to Native Hope, which works to undo the injustice done to Native Americans, the National Crime Information Center cited 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls in 2016, although the U.S. Department of Justice’s federal missing person database, NamUs, only logged 116 cases.

As of 2022, there were 4,089 cases reported of missing 0-17-year-olds and 1,398 cases of missing 18+ year-olds, according to FBI statistics. The bipartisan Savanna’s Act was signed into law in October 2020 to improve the federal response to Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP), including by increasing coordination among Federal, State, Tribal, and local law enforcement agencies.

Native Hope’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous noted on its website: “There is widespread anger and sadness in First Nations communities. Sisters, wives, mothers, and daughters are gone from their families without clear answers. There are families whose loved ones are missing—babies growing up without mothers, mothers without daughters, and grandmothers without granddaughters. For Native Americans, this adds one more layer of trauma upon existing wounds that cannot heal. Communities are pleading for justice.”

Final Call staff contributed to this report.