If you listened to African leaders addressing the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA-78) as I did, you would have discovered a singular unanimous message of being fed up with Western powers’ dominance over global affairs. In unison, African leaders expressed dissatisfaction with living in a world that pretends present-day economic and social conditions are not connected with historical injustices.

Much of the continent has logged roughly a 60-year time span of independence. However, it has been more like neocolonial dependence, where Western powers milk Africa for its raw materials and natural resources, only to be saddled with unpayable debt via a post-World War II Bretton Woods global financial system.

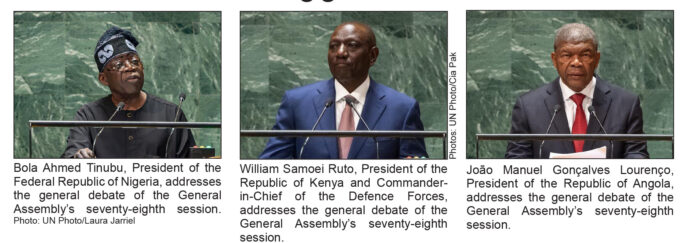

Nigerian President Bola Tinubu, addressing the UNGA-78, urged his peers to see the continent not as “a problem to be avoided” but as “true friends and partners.” “Africa is nothing less than the key to the world’s future,” said Tinubu, who leads a country that, by 2050, is forecast to become the third most populous in the world.

In his address, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo blamed Africa’s present-day challenges on “historical injustices” and called for reparations for the slave trade. President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa and a member of BRICS said the continent is poised to “regain its position as a site of human progress” despite dealing with a “legacy of exploitation and subjugation.”

With the largest bloc of countries at the UN it is understandable that African leaders increasingly demand a bigger voice in multilateral institutions, said Murithi Mutiga, program director for Africa at the Crisis Group. “Those calls will grow especially at a time when the continent is being courted by big powers amid growing geopolitical competition.”

“Africa has no need for partnerships based on official development aid that is politically oriented and tantamount to organized charity,” President Felix-Antoine Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of the Congo said. “Trickling subsidies filtered by the selfish interests of donors will certainly not allow for a real and effective rise of our continent.”

Tshisekedi’s country has the world’s largest reserves of cobalt and is also one of the largest producers of copper, both critical for clean energy transition.

According to Mozambican President Filipe Nyusi, what the continent needs is a more inclusive global financial system. In such a system, Nyusi said, Africans can participate as “a partner that has (a) lot to offer to the world and not only a warehouse that supplies cheap commodities to countries or international multinational corporations.”

President Wilson Ruto of Kenya, who is also the chair of the Intergovernmental Authority of Development in East Africa (IGAD), emphasized Africa having suffered the exploitation of the Global North, is not looking for handouts.

He said, “We as Africa have come to the world, not to ask for alms, charity or handouts, but to work with the rest of the global community and give every human being in this world a decent chance of security and prosperity.”

Julius Maada Bio, president of Sierra Leone assumes a non-permanent seat at the Security Council’s 2024-2025 session after 53 years. He called for reforming the Security Council, particularly repeating Africa’s yearly UNGA demands for two permanent and five non-permanent seats.

Echoing Sierra Leone, Joao Manuel Goncalves Lourenco, president of Angola, emphasized that the reform of the Security Council should reflect the reality of the times. Africa must be granted permanent membership on the Council. He also stressed the need to comply with resolutions on the embargo against Cuba and the decades-long conflict in the Middle East between Israel and Palestine.

The Security Council was created in 1946 by the winners of World War II. It comprises 15 members, five of them—the United States, Great Britain, France, China and Russia—are permanent, with veto power, while 10 are non-permanent members that serve for two years on a rotational basis. Critics of the Council say it represents an international order that no longer exists. The permanent members have historically made binding decisions concerning global issues, including invasions of member states like Libya in 2011.

Probably the most damning condemnation of the Security Council’s historical misuse of its power came in 2009, at the UNGA, from then-leader of Libya, Muammar Gadhafi, who at the time also served as the chair of the African Union.

Col. Gadhafi noted that the UN Preamble states, “if armed force is used, it must be a United Nations force—thus, military intervention by the United Nations, with the joint agreement of the United Nations, not one or two or three countries using armed force. The entire United Nations will decide to go to war to maintain international peace and security. Since the establishment of the United Nations in 1945, if there is an act of aggression by one country against another, the entire United Nations should deter and stop that act.”

He later added, “Permanent (seat on UN Security Council) is something for God only. We are not fools to give the power of veto to great powers so they can use us and treat us as second-class citizens. … Veto power should be annulled,” he added before tossing the UN charter over his shoulder. Follow @JehronMuhammad on X, formerly known as Twitter