Homelessness has been an enduring challenge in the United States for decades. Despite periods of the nation’s economic progress and prosperity, there remains a significant portion of the population living without stable shelter.

Cars, RV campers, buses and tents used for shelter used to be the mark of homeless encampments relegated mostly to communities like Skid Row, Los Angeles and other similar smaller communities across the country. But the numbers of unhoused individuals and families are growing, as evidenced by tent cities and cardboard boxes turned into living spaces surfacing beyond relegated dark and invisible outskirts or beneath bustling neighborhoods.

According to data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), on any given night in 2022, 600,000 people experienced homelessness, with the majority living in unsheltered locations like parks, streets, under bridges and in abandoned cars. And that number has been steadily rising.

“We say that housing is a human right, and where we are at now is this neo-liberal, capitalist paradigm, which has created a surplus population—homeless people,” stated Bilal Mufundi Balagoon, a San Francisco Bay area homeless advocate who was once unhoused. “They have no solutions except policing homelessness,” Mr. Balagoon told The Final Call.

The problem of homelessness is not evenly distributed across the country, with certain states and cities bearing a disproportionate burden. Cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York City have become emblematic of the crisis, as their high costs of living and housing shortages push more individuals and families into homelessness, according to advocates. These urban centers often serve as hubs for economic opportunities, but the glaring wealth disparities contribute to the problem.

“Housing affordability has been an issue for many years now, and particularly here, in Boston,” stated HUD Deputy Secretary Adrianne Todman, during a dialogue on “America’s housing crisis: Policy levers to drive change,” hosted by Howard Koh, Harvey V. Fineberg Professor of the Practice of Public Health Leadership at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Kennedy School, on September 14. He is also Faculty Chair of the school’s Initiative on Health and Homelessness.

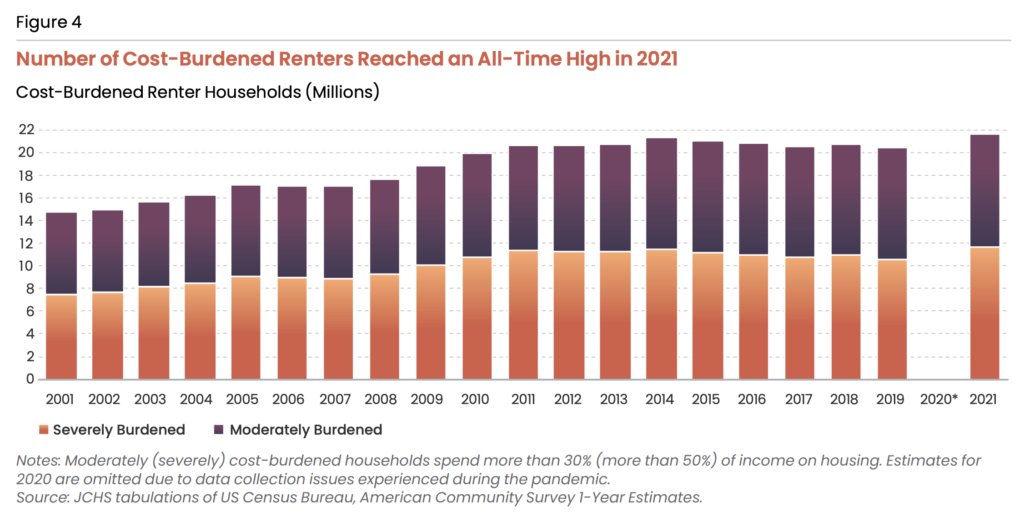

He noted that part of the problem is the average household is spending 30 percent or more on rent, according to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. Between 2019 and 2021, that number increased by 1.2 million to a record 21.6 million households, according to its State of the Nation’s Housing 2023 report. Among these, 11.6 million were severely cost burdened, spending more than 50 percent to their income on housing, it continued.

Commitments to build affordable housing is tricky, argued Mr. Balagoon, adding that those he services cannot afford it. “They say affordable for who? … It’s not affordable to the people I’m working with because most of them are low income, (on) Social Security, or they’re working at McDonald’s or something,” he stated.

“There’s no political will to eradicate it. They could eradicate poverty, which gives rise to homelessness, in a month! Because they have the money, but the bulk is either going for the police or the military, to maintain White supremacy hegemony,” argued Mr. Balagoon

HUD’s action plan includes Pro Housing, a new $85 million program to continue to motivate states and localities to reduce the barriers to more housing supply, stated Deputy Todman. “Whether it is creating new zoning rules, whether it is coming up with new ideas around innovative housing types, like ADUs (Accessory Dwelling Units, i.e., granny flats, in-law units, backyard cottages, secondary units), we are driving and accepting applications from leaders on things that they want to invest in to continue their supply mission as well,” stated Deputy Todman.

In addition to homeownership and fair housing, HUD has implemented several first-of-its-kind initiatives, such as an unsheltered unhoused program, which provides $500 million across the country to address unhoused neighbors, according to Deputy Todman.

HUD typically provides its grant funds to local homelessness agencies so they can work with their shelter populations and other homeless subpopulations, she said. But they began to see more and more that there was an acute need inside of the unsheltered population, she added.

“These are the individuals that we see, sadly, on the streets. We see them in encampments,” she said.

Who bears the brunt of homelessness?

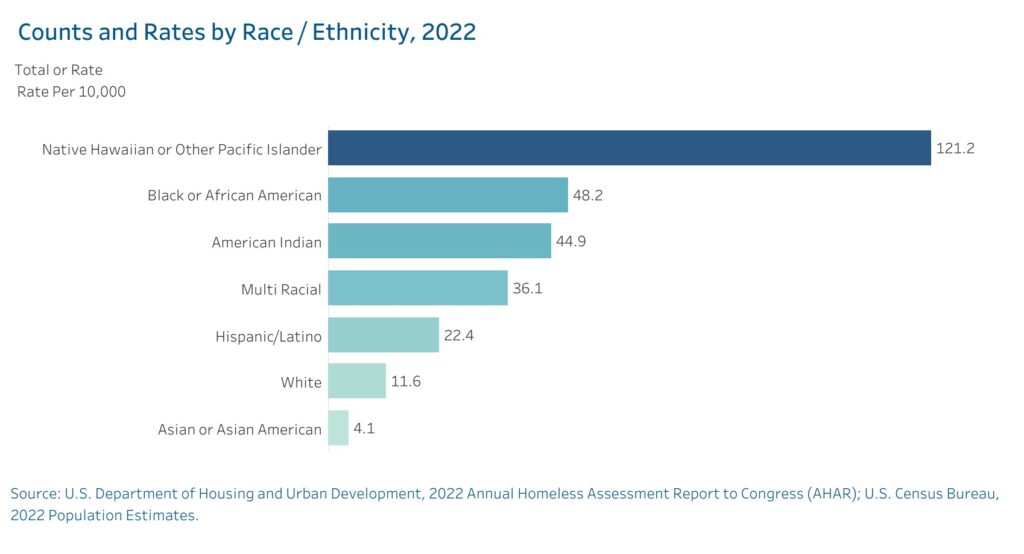

While homelessness affects people from all walks of life, certain groups are more vulnerable and disproportionately impacted by this crisis: Blacks, Latinos and Indigenous/Native Americans have higher rates of homelessness than their White counterparts—and, in some cases, far higher, according to the “State of Homelessness: 2023 Edition,” compiled by the National Alliance to End Homelessness. It is a nonprofit, non-partisan organization committed to preventing and ending homelessness in the U.S.

Within the White group, 11 out of every 10,000 people experience homelessness. For Black people, that number is more than four times as large—48 out of every 10,000 people. Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders particularly stand out as having the highest rates, with 121 out of every 10,000 people experiencing homelessness, according to the report.

Further, the racial and ethnic groups with the highest incidences of homelessness have extensive histories of experiencing oppression, including displacements from land and property and exclusions from housing opportunities, such as laws and policy decisions passed by local, state, and federal governments, which have promoted discriminatory patterns that continue to this day, the report continued.

Effectively addressing homelessness will likely require invested partners to account for America’s history, and that history’s influence on current culture, policy, and practice, the report recommended.

In terms of the inescapable themes of racial inequities and disparities still plaguing the U.S., Deputy Todman stated that a piece of the Fair Housing Act named “affirmatively furthering fair housing,” has not been activated. “That part of the Fair Housing Act is intended to say, ‘Look. There has been a history—not my opinion, not anybody’s opinion—a history in this country of discrimination and the impact of that history still lingers in the way that our systems work,” she stated.

Of people experiencing homeless, 22 percent are chronically homeless individuals (or people who have experienced long-term or repeated incidents of homelessness), six percent are veterans, and five percent are unaccompanied youth under 25 (considered vulnerable to their age), according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

Federal funding falling short

For her part, Democratic Congresswoman Cori Bush of St. Louis, Missouri, proposed the Unhoused Bill of Rights, the first federal resolution to declare unalienable rights for unhoused persons and provide solutions to permanently end the crisis by 2025, according to a press release outlining the bill.

The Unhoused Bill of Rights provides a framework for concrete steps the federal government must take to permanently house the nearly 1.5 million women, children, veterans, and people struggling to survive on the streets, according to the press release. “The dire urgency of the unhoused crisis has been exacerbated by the deadly global pandemic that continues to wreak havoc on our most vulnerable communities.

Nearly 10 million households and 15 million people are currently at risk for eviction following the expiration of the federal eviction moratorium. We must champion policies that allow people to remain in their homes and guarantee housing for everyone,” it read.

According to the Native Organizers Alliance Action Fund, which supports and mobilized Native peoples in the protection of their lands, waters, resources, and ways of life, they are on the front lines of the unhoused crisis, with the highest rates of homelessness in the United States.

While Native people make up less than three percent of the U.S. population, they make up more than 10 percent of the unhoused population nationally, stated Judith LeBlanc (Caddo), the organization’s executive director in a recent press release, announcing its support of Rep. Bush’s legislation.

Recently, stated Ms. LeBlanc, “more than 100 people were kicked out of a mostly Indigenous Minneapolis homeless encampment called the ‘Wall of Forgotten Natives.’ After genocide, forcing Indigenous peoples off our land, and ongoing racist inequities, the federal government has a responsibility to our communities.”

“It’s a very sad state of affairs that a country as big as this, that has so many individuals, families, veterans, at a place where they cannot house themselves or at a mental capacity where their mental health is challenged,” stated community activist and advocate Hector Perez Pacheco, a Quechua from the Confederations of Tawantisuyu. “The traditions of our communities and our people are at a place where it’s severe. … Driving in Los Angeles, you cannot go about any street or place without seeing the plight of our community,” he told The Final Call.

Mr. Pacheco commended non-profit organizations working toward the problem for their efforts, acknowledging that everyone has good intentions. But more is required to produce impactful results, he urged.

Recently, HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge announced that HUD is awarding $128 million to support affordable housing in Tribal communities. These awards provide American Indian and Alaska Native communities with funding to address challenges in ways that best serve their Tribes.

A challenge is that not enough of such funding is getting utilized or being produced in terms of policies, according to Mr. Pacheco.

“Government programs do a very poor job to outreach and announce what’s out there. They fund the program, but they don’t fund getting the word out to the people,” Mr. Pacheco told The Final Call. He added, “The people that need these programs are underneath the bridges, by the river, in Skid Row, places that are undesirable for people to go on and in some cases, they’re dangerous, but that’s those places where you need to get the information out, to let people know!”

Also, in Los Angeles, on the campaign trail before her election in 2022, Mayor Karen Bass promised to marshal federal, state, county and city government resources around a single plan to tackle homelessness in L.A.

Mayor Bass promised to: House 15,000 people by the end of year one and build more temporary, affordable and permanent supportive housing; transition individuals from the streets to housing and services, and end street encampments; equip the unhoused with job training and employment services to reenter the workforce; and prevent homelessness and keep neighbors housed.

At Final Call presstime, inquiries for an interview with Mayor Bass (or a mayoral spokesperson) and Rep. Bush had not been returned. However, Mayor Bass announced in August that she has secured a critical permanent housing agreement with the Federal Housing Department, which should allow Angelenos in temporary housing, including in tiny homes, A Bridge Home housing (safe places to sleep and connect to resources while people wait for permanent housing), or motels through Inside Safe, to be placed in permanent housing faster by cutting through bureaucracy.