Viola Fletcher was just seven years old when she was forcibly displaced from her hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma, by an armed mob which destroyed the predominantly Black enclave of Greenwood, killing hundreds of residents.

Together with her grandson, Ike Howard, the 109-year-old Ms. Fletcher came to UN Headquarters at the end of August to commemorate the UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) International Day of Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition.

Standing in front of the Ark of Return monument, Ms. Fletcher and Mr. Howard spoke with UN News to discuss the legacy of slavery and the possibility of reparations for those with ancestral ties to the horrific trade.

Black Wall Street

The Greenwood district in Tulsa was colloquially known as Black Wall Street due to the wealth and opportunities it provided.

Segregation in Oklahoma during the 1920s severely restricted the socioeconomic status of Black residents, making Greenwood a rare neighborhood where they could thrive and attain success.

There were Black-owned grocery shops, furniture stores, and a movie theatre, an exceptional rarity for Black communities at the time.

On May 30, 1921, however, the neighborhood was plunged into what would eventually become one of the worst incidents of racially motivated violence in United States history.

A young Black man was accused of assaulting a White teenage girl and subsequently arrested before news of his alleged crime had been published in sensationalized newspapers across the city. To this day, the true extent of the physical contact between the two is not known.

These accusations caused a crowd of armed White men to gather outside the courthouse where Mr. Rowland was being held. To protect Mr. Rowland from being lynched, a group of armed Black men began to file into the area.

The White crowd reportedly became enraged, and racist comments and expletives quickly escalated into an exchange of gunfire.

‘Some of them made it, so many did not’

The ensuing conflict quickly engulfed the entire neighborhood of Greenwood. White men fired indiscriminately at Black residents fleeing the violence and proceeded to burn over 35 blocks of the neighborhood, resulting in the displacement of over 10,000 Black residents. The number of lives lost has never been confirmed, although some estimates place the death toll as high as 300.

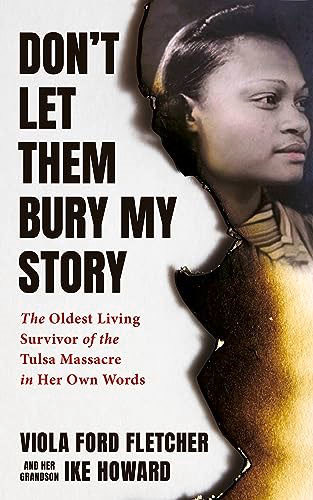

Ms. Fletcher was one of the displaced. In her memoir, “Don’t Let Them Bury My Story: The Oldest Living Survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre in Her Own Words,” Ms. Fletcher recalls seeing families desperately fleeing the carnage, with many being gunned down in the process.

“My eyes burned and watered from the smoke and ash, but I could still see everything so clearly. People ran clinging to their loved ones toward the railroad or any path out of the town that was not overrun with armed White men,” she writes.

“Some of them made it. So many did not. We passed piles of dead bodies heaped in the streets. Some of them had their eyes open, as though they were still alive, but they weren’t.”

‘To reconcile means to reconcile’

On August 23, 102 years later, Ms. Fletcher and her grandson held a libation ceremony in front of the Ark of Return at UN Headquarters. The memorial was constructed by Haitian American artist Rodney Leon for the UN in 2015. According to Mr. Leon, the memorial is intended to be a “spiritual place of return” for all international victims of the Atlantic Slave Trade.

The ceremony was intended to coincide with the International Day and as a reminder of why the legacy of slavery must continue to be highlighted. Also discussed was the possibility of reparations for those with ancestry tied to the slave trade.

“To reconcile means to reconcile. We need reparations, period. It’s time to make it right, worldwide. We need reparations around the world,” said Mr. Howard.

“Some countries and some cities in the United States are taking steps to incorporate reparations. If there is a will there’s a way. We can get this done,” he added.

‘Dominoes are starting to fall’

According to her grandson, Ms. Fletcher has been pleased with the progress that has been made in her lifetime. Having lived through the post-reconstruction “Jim Crow” era, the civil rights movement, and, most recently, the Black Lives Matter movement, Ms. Fletcher has observed first-hand the evolving attitudes toward the legacy of the slave trade.

“She feels good about the movement that’s ongoing across the country. Dominoes are starting to fall. It’s a blessing to see a ray of sunshine, a ray of hope in these situations,” said Mr. Howard, speaking on behalf of his grandmother, who now finds it hard to speak audibly.

“This energy is amazing because those same slaves are a part of the history of the worst race massacre in U.S. history, called the Tulsa Race Massacre,” he continued.

‘Generations of exploitation’

While speaking to mark the UN’s International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in March, UN Secretary-General António Guterres acknowledged the legacy of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and labeled it an “evil enterprise.”

“Millions of African children, women, and men were trafficked across the Atlantic, ripped from their families and homelands—their communities torn apart, their bodies commodified, their humanity denied. The history of slavery is a history of suffering and barbarity that shows humanity at its worst,” Mr. Guterres said.

“The legacy of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade haunts us to this day. We can draw a straight line from the centuries of colonial exploitation to the social and economic inequalities of today,” he added.

Officially, the UN has taken a position that encourages Member States to create reparation frameworks for families impacted by the legacy of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.

“We must reverse the consequences of generations of exploitation, exclusion, and discrimination, including their obvious social and economic dimensions through reparatory justice frameworks,” the UN chief said. (UN News)