New research from the March of Dimes shows that for millions of women in the United States, it’s increasingly difficult to access maternity care. The report is one of the largest analyses on maternity care access and offers insight into the factors that impact pregnancies in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico.

“A person’s ability to have a healthy pregnancy and healthy birth should not be dictated by where they live and their ability to access consistent, quality care but these reports shows that, today, these factors make it dangerous to be pregnant and give birth for millions of women in the United States,” Dr. Elizabeth Cherot, March of Dimes president and chief executive officer, said in a statement on the group’s website on August 3.

“Our research shows maternity care is simply not a priority in our healthcare system and steps must be taken to ensure all moms receive the care they need and deserve to have healthy pregnancies and strong babies. We hope the knowledge provided in these reports will serve as a catalyst for action to tackle this growing crisis.”

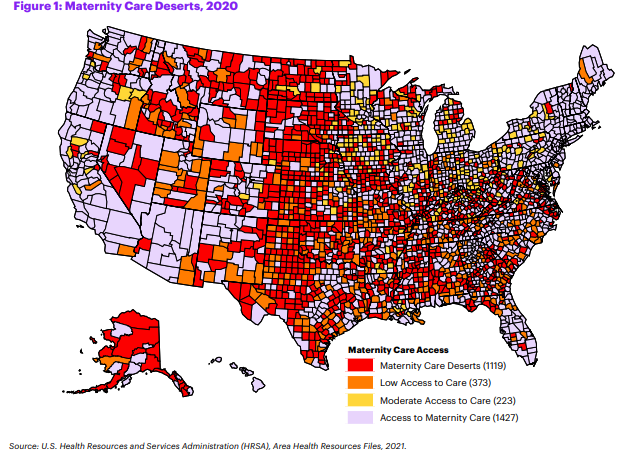

More than one-third (36 percent) of U.S. counties are considered maternity care deserts, which are defined as counties without a hospital or birth center offering obstetric care and without any obstetric providers. Since 2018, the March of Dimes has researched access to U.S. maternity care through frequent reports. This new data shows increasing areas with less access to care, impacting women before, during, and after their pregnancy journey.

The reports show access to care continues to decline:

• The loss of obstetric units in hospitals was responsible for decreased maternity care access in 369 counties since the 2018 report, nearly 1 in 10 counties across the U.S.

• Seventy additional counties have been classified as maternity care deserts due to a loss of obstetric providers and obstetric units in hospitals, since the initial report in 2018.

• More than 32 million reproductive-age women are vulnerable to poor health outcomes due to a lack of access to reproductive healthcare services, like family planning clinics and skilled birth attendants.

• States with the highest rates of maternity care deserts include North Dakota, South Dakota, Alaska, Oklahoma, and Nebraska, states with more rural populations.

In North Dakota 71.7 percent of counties are described as maternity care deserts compared to the national average of 32.6 percent. That means 43.8 percent of women there had no birth hospital within 30 minutes compared to a national average of 9.7 percent.

According to research, the farther a woman travels to receive maternity care, the greater the risk of maternal morbidity and adverse infant outcomes, such as stillbirth and NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit) admission.

The report detailed how longer travel distances can cause financial strain on families and increased prenatal stress and anxiety. The distance a woman must travel to access care becomes a critical factor during pregnancy, at the time of birth, and in the case of emergencies. Nationwide closures of birthing hospitals have contributed to increased distance and travel time to care, especially in rural areas. Hospital closures and a shortage of providers are driving change in maternity care access, especially within rural areas and among Black, Indigenous and other people of color.

Dr. Erin Stewart practiced family medicine with the Indian Health Service in Kayente, Arizona. “We don’t birth babies. We do obstetrics care but when it comes time to deliver, families have to travel long distances. They may go to Tupelo City, hours away, or Chinle, also hours away or even Phoenix, which is five hours away. That’s a problem, especially if the birth doesn’t go well,” Dr. Stewart told The Final Call.

“The pregnant women that come to the health center are negatively impacted by the lack of a birthing center. They worry about problems and complications. What if their car breaks down on the way to deliver? What if they don’t get there in time? Who will help them?”

Limits in accessing care are just the beginning for marginalized women. Environmental factors, socioeconomic issues, and chronic health conditions also play a large role in pregnancy and birth outcomes. Unemployment and housing conditions consistently indicate a higher percentage of inadequate prenatal care, especially for Black, Latino and Indigenous women.

Eight out of 10 maternity care deserts have higher numbers of pregnancies with pre-existing chronic health conditions (hypertension, diabetes, overweight or underweight, and smoking), which can increase the risk for conditions like preeclampsia and preterm birth. This creates an additional challenge for women living in communities lacking access to trained providers and well-equipped facilities.

“Every baby deserves the healthiest start to life, and every family should expect equitable, available, quality maternal care,” Dr. Cherot added. “These new reports show that the system is failing families today but paints a clear picture of the unique challenges facing mothers and babies at the local level—the first step in our work to put solutions in place and build a better future for all families.”