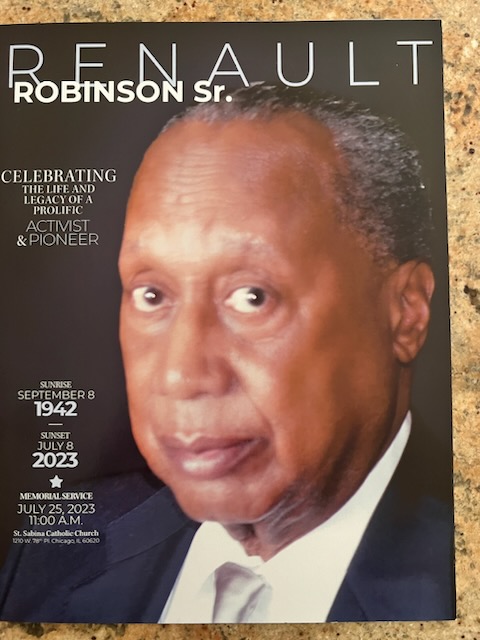

CHICAGO—Renault Robinson, who stood up against police racism and brutality and mobilized protection for the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan in the early stages of his rebuilding the work of the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad, was recognized and honored at a funeral and memorial on July 25. Mr. Robinson died on July 8. He was 80 years old.

“He didn’t come into the world to bow to the world, he came into the world to change the world,” said Min. Farrakhan to the packed room of activists, retired and current police officers and loved ones during the memorial service for Mr. Robinson at St. Sabina Catholic Church. Mr. Robinson is survived by his wife Annette, four sons, 10 grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

In 1968, Renault Robinson, one of a few Black officers on the force, co-founded the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League (AAPL) within the Chicago Police Department (CPD). The organization aimed to enhance police relations and services for the Black community and advocate for increased representation of Blacks in policymaking positions within the department.

Less than 10 years later, the AAPL played an important role during a vulnerable moment in the Nation of Islam’s history. When Min. Farrakhan began working in 1977 to ensure that Elijah Muhammad’s name would not be written out of history, Mr. Robinson and other Black police officers decided to make sure the Minister stayed safe.

“In trying to rebuild the Honorable Elijah Muhammad’s work, it was very dangerous because everyone wasn’t that happy to see Elijah Muhammad come back … . The man that made it possible for me to get started is the man we honor today–Renault Robinson,” said Minister Farrakhan.

“Before I had all these young men around me,” he said, glancing towards the Fruit of Islam seated behind and beside him as he spoke, “there was nobody.” “I would teach in one city and Renault would call, and the Patrolmen League would come, and before you knew it, the Minister was teaching here and there, and the followers and the adherents to the doctrine of the Afro-American Police League became my protectors,” Min. Farrakhan reflected.

“I have to admit, I never saw so many guns in my life,” said the Minister with a smile, “but they were righteous guns. And because of that, I am here today, with soldiers all over the world because Renault and Howard Saffold made it possible for me. I thank God for Renault and I thank him for his family and his beautiful wife.”

The impact of the AAPL was felt nationwide, including an increase in Black and Latino officers. It triggered civil rights lawsuits against the Chicago Police Department for discriminatory treatment of Black and Latino citizens. Despite the progress, this endeavor came at a personal cost for Mr. Robinson, a model policeman before the AAPL’s formation, with an impressive efficiency rating and numerous citations for outstanding police work.

Mr. Robinson and other members faced challenges, including suspensions, charges for minor infractions, reassignments to less desirable positions, and threats of dismissal, feces left in lockers, and racial epithets left in bathrooms as the CPD attempted to dismantle the organization.

One public example of discrimination was when Mr. Robinson was assigned to patrol the alley behind police headquarters, cited in the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision against the Chicago Police Department, resulting in better representation for minorities in police hiring and promotions.

Despite the hardships, Mr. Robinson remained steadfast, using his position to denounce racism within the police department. He criticized controversial events, such as the tragic raid resulting in the death of Black Panther Party members Fred Hampton and Mark Clark. He spoke out at the orders of then-Mayor Richard J. Daley to “shoot to kill” mourners after the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the dragnet operation led by infamous Chicago police commander Jon Burge.

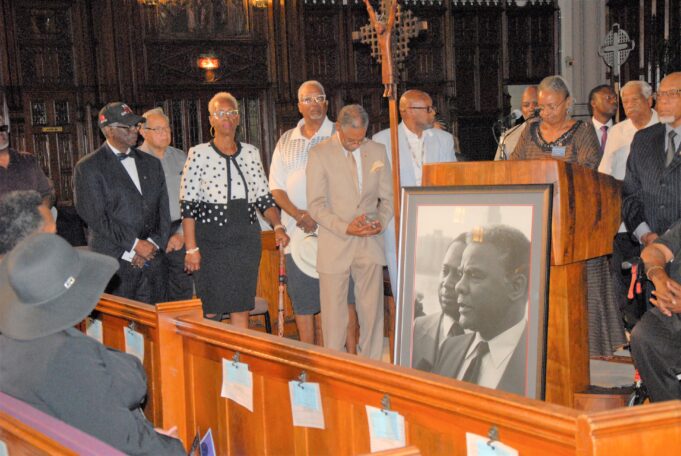

Family members, retired police officers Howard Saffold, Frank Lee, Gus Thomas, longtime Judge William Hooks, and many others poured into the church to pay tribute to his bravery, compassion, love, and commitment to Black people.

“Renault Robinson is the one who said all the bullet holes came from the outside,” said Judge Hooks referring to Robinson visiting the crime scene where Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were killed. Calling him a real-life superhero, Mr. Hooks called for a street to be named in his honor at the 35th and Michigan police station next year.

Mr. Robinson’s efforts led to an investigation into CPD practices, and in 1974, he and the U.S. Department of Justice filed a discrimination lawsuit against the Chicago Police Department, which ruled in favor of non-White officers and women.

“Renault Robinson not only refused to assimilate into the racial culture of the Chicago Police Department, rather he chose to attack it at its roots, no matter the cost or sacrifice,” said Father Michael Pfleger, who performed the eulogy during the memorial service. “In a day of pop-up activists, Renault was a long-distance runner who spent his life making a difference.”

Throughout his journey, Mr. Robinson found support in Harold Washington, a member of the Illinois House of Representatives who later became Chicago’s first Black mayor. Mayor Washington appointed him head of the Chicago Housing Authority. After his service on the board of the Chicago Housing Authority, Mr. Robinson established his own company in the staffing and building maintenance industries, retiring in 2018.

—Toure Muhammad, Contributing Writer