[Section Editor’s Note: The following contains an excerpt from “Waging War By Zip Code” by Student Minister Dr. Wesley Muhammad under the section “How Food in Black Neighborhoods is Weaponized,” from Chapter 16 published in 2019. Full citations and footnotes are available in his original full report.]

We know we are in a bona fide “Food Crisis” when it could be said that in Black neighborhoods “it is easier to get fried chicken than a fresh apple.” Fast food has become “entrenched” in urban neighborhoods and diets. “NHANES [National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey] data indicate that non-Hispanic blacks are more likely than other racial/ethnic groups to eat fast food.”

As Dr. Chin Jou documents in her Super Sizing Urban America, How Inner Cities Got Fast Food With Government Help, “many urban, low-income African-American neighborhoods are both saturated with fast food and disproportionately affected by the obesity epidemic.

According to Dr. Andrea Freedman, fast food is “oppression through poor nutrition”: Fast food has become a major source of nutrition in low-income, urban neighborhoods across the United States. Although some social and cultural factors account for fast food’s overwhelming popularity, targeted marketing, infiltration into schools, government subsidies, and federal food policy each play a significant role in denying inner-city people of color access to healthy food.

The overabundance of fast food and lack of access to healthier foods, in turn, have increased African American and Latino communities’ vulnerability to food-related death and disease.’ Structural perpetuation of this race- and class-based health crisis constitutes “food oppression.”

This “structural perpetuation” is obvious:

West Oakland, California, a neighborhood of 30,000 people populated primarily by African Americans and Latinos, has one supermarket and thirty- six liquor and convenience stores. The supermarket is not accessible on foot to most of the area’s residents. The convenience stores charge twice as much as grocery stores for identical items.

Fast food restaurants selling cheap and hot food appear on almost every corner. West Oakland is not unique. The prevalence of fast food in low income urban neighborhoods across the United States, combined with the lack of access to fresh, healthy food, contributes to an overwhelmingly disproportionate incidence of food-related death and disease among African Americans and Latinos as compared to whites.

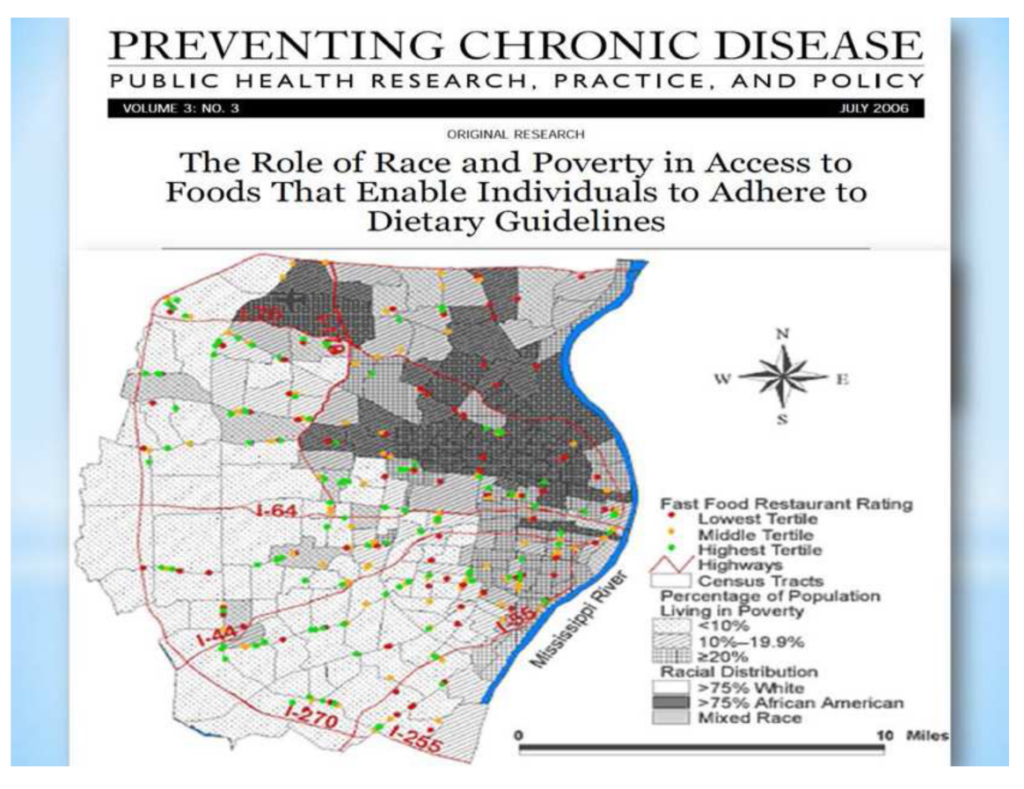

A 2006 audit by Elizabeth A. Baker et al. of food quality options in the St. Louis area found that the highest quality supermarkets that provide the best options for meeting dietary guidelines (fresh fruits and vegetables, lean, low-fat and fat-free meats and dairy options) clustered in white higher income communities and none in Black census tracts.

While the poorest quality fast food restaurants and poor quality super markets – to the extent that super markets exists at all – that offer low quality food (high fat), disallowing consumers to meet recommended dietary intake clustered in predominantly Black census tracks. In a 2004 study researchers mapped fast food restaurants in New Orleans and discovered that shopping districts in communities that were 80% Black were exposed on average to six fast food outlets more than majority white areas of the same size.

Fast-food restaurants are geographically associated with predominately black and low-income neighborhoods after controlling for commercial activity, presence of highways, and median home values. The percentage of black residents is a more powerful predictor of [fast food restaurant density] than median household income. Predominantly black neighborhoods (i.e., 80% black) have one additional fast-food restaurant per square mile compared with predominantly white neighborhoods (i.e., 80% white).

These findings suggest that black and low-income populations have more convenient access to fast food. More convenient access likely leads to the increased consumption of fast food in these populations, and may help to explain the increased prevalence of obesity among black and low-income populations.

The Origin of Black America’s Fast-Food Dependency

While it true that Black and Hispanic communities disproportionately patronize fast food restaurants, this is a new phenomenon. But despite its current popularity, there was a time not too long ago when fast food was entirely absent from the diets of inner-city African-Americans. McDonald’s and most of the major fast food chains only opened in urban areas starting in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Brady Keys, a former pro-football player and African-American fast food franchising pioneer, recalls that before the emergence of fast food, African Americans consumed more meals at home; there was simply “no opportunity to eat anywhere else [relatively cheaply].”

And believe it or not, Black People had a better diet than Whites in many cases. In a 1939 U.S. Department of Agriculture dietary survey it was revealed that during the summer months African Americans’ diets contained more vitamins, minerals, and proteins than whites’ diets in cases where households spent the same money on food.

In 1965, African Americans were still consuming dietitians recommended quantities of fat, fiber, fruits, and vegetables at twice the rate of whites. However, by 1996 a near-reversal had occurred. “Dietary surveys indicated that 28 percent of African Americans, and only 16 percent of whites, now consumed unhealthy diets.”

This diet revolution was caused largely by the new availability of fast food. During the heyday of fast food in the United States-roughly the 1970s to 1990s-Americans’ appetite for Big Macs and Whoppers seemed to cut across socioeconomic divides more than they do now…Today’s typical fast-food habitué is more likely to be relatively young, low-income, and African American (emphasis added).

It was the relentless targeting of the Black poor, with the aid of the U.S. Government, that transformed the urban food landscape: “federal programs were…part of a remaking of inner cities as fast food havens” Fast food companies’ aggressive pursuit of African Americans since the early 1970s has been reflected in the inordinate share of their promotional budgets dedicated to reeling in minority consumers.

One report in 1990 found that the three major fast-food chains-McDonald’s, Burger King, and Wendy’s ear marked up to one-fifth of their advertising budgets on African American consumers even though African Americans made up only about 12 percent of the total U.S. population at the time. The fast-food industry is particularly “unrelenting in its appeal to young urban African Americans.”

According to one 2012 report Black children (ages two through eleven) and teenagers viewed almost 60% more television advertisements for fast food than white children and teens. The Washington Post took notice of this “food oppression” in 2014 reporting “The disturbing ways that fast food chains disproportionately target black kids,” noting the research that “fast food chains (such as Popeye’s and Papa John’s) in predominantly black neighborhoods were more than 60 percent more likely to advertise to children than in predominantly white neighborhoods.”

The concentration of African Americans into segregated neighborhoods made us “compact sales targets,” in marketing jargon, and made the direct, geographic targeting of us easy and efficient: waging war by zip codes. As Naa Oyo A. Kwate points out: A primary reason why Black neighborhoods have a high prevalence of fast-food restaurants is because African Americans are actively sought by fast food companies, and segregation creates a ready, spatially concentrated target area.

From a purely rational business perspective, the high prevalence of fast-food restaurants in Black neighborhoods is itself suggestive of purposeful targeting. When opening a business, owners must consider location characteristics, including neighboring shops and local business climate, the crime rate, quality of public services, condition of homes, buildings, and lots, relationship to competition, and the spatial relationship to the target market (…).

In many Black neighborhoods, such a location analysis would reveal: a retail climate that generates few customers; a relatively high crime rate; public services that have faced years of cutbacks and neglect; visibly deteriorated buildings; and several competing fast-food restaurants. In other words, there would be few incentives to open a store in a neighborhood with these characteristics, unless a primary goal was to target the individuals who reside there. And it seems to be urban young Black men who are the real target audience.

Living near fast food restaurants may indeed constitute a “risky” physical environment, at least if one is low-income and male. A 2011 analysis of a longitudinal nationwide survey of 5,155 U.S. adults between the ages eighteen and thirty found that low-income men who lived within 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) of fast-food chain restaurants consumed fast food more frequently than those who did not.

These low-income men, researchers reasoned, were less likely to own cars, which made them more dependent on their immediate environs for meals and other services. This geographic constraint, coupled with limited cash for food, made it more likely that these low-income men would be ordering double cheeseburgers…off McDonald’s Dollar Menu.

The Dollar Menu was targeted toward poor Black people, a strategy to ensnare African Americans into a fast-food diet. As McDonald’s vice president for United States business research Steve Levigne quasi-confessed: “The Dollar Menu appeals to lower-income, ethnic consumers…It’s people who don’t always have $6 in their pockets.”190 This disproportionate patronizing of fast food by Black and Hispanic communities is thus not an organic or natural phenomenon but the desired end of a government and industry process.

And this process has contributed to the “obesity crisis” of Black America. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in 2015 African Americans were 1.4 times as likely as Whites to be obese. 69.6% of Black men and 82% of Black Women are either obese (body mass index > 30.0) or overweight (body mass index > 25.0). “African American Women have the highest rates of being overweight or obese compared to other groups in the U.S.,” HHS.gov reports.

Student Minister Dr. Wesley Muhammad is a member of the Nation of Islam Shura Executive Council, the N.O.I. Research Group and is an author with a PhD. in Islamic Studies.