by Charlene Muhammad

National Correspondent @sischarlene

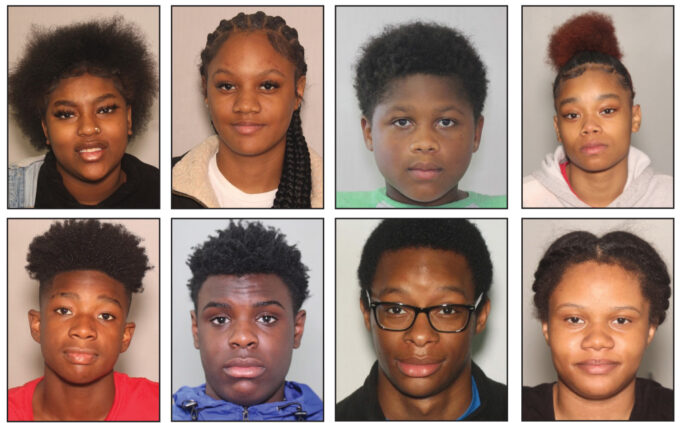

A coalition of Black pastors are on a mission to help find more than 30 children reported missing during a span of two weeks in Cleveland, Ohio. A missing persons poster circulated in media has depicted photos of at least 13 of the children, who appeared to be Black.

“Something needs to be done,” said Rev. Dr. Larry Macon, pastor of Mt. Zion Church in Oakwood Village and a member of United Pastors in Mission founded in 2015. “Kids were not just missing. They were lost! We didn’t know how long they were missing, and what condition they’d moved into, whether or not they were being sex-trafficked, found in drug houses, beaten, whether or not they’d been murdered.”

On June 13, the alliance of pastors held a news conference at his church to inform the community and challenge people to come together to find out what is happening to these children. Their research found in 2022 there were more than 2,400 children in Cuyahoga County who were missing.

“We discovered that probably about 85-90 percent of them (missing as of 2022) returned home by the end of the year from Cleveland. However, we don’t have a county assessment of the missing kids. They have not yet responded to us,” Pastor Macon said.

Sergeant Jennifer Ciaccia, public information officer for the Cleveland Division of Police, told The Final Call they were not providing interviews at press time. However, Cleveland Police Chief Wayne Drummond has said investigators have uncovered nothing that would indicate individuals targeting the children, using them in human trafficking or otherwise. He vowed to bring resources to bear should such information surface.

Chief Drummond, who spoke during a video news conference held on June 14 to bring clarity and clear up misinformation, further said the vast majority of those missing are runaways, sometimes habitual.

“If you look at the stats, they are very startling,” Chief Drummond said. “Year-to-date, there are 1,072 missing juveniles reported, but also, the number returned is 1,020.”

Five detectives in the city of Cleveland are assigned to missing persons, and take the issue with missing children very seriously, but it is also important to have context, continued Chief Drummond.

“I don’t say that to minimize missing juveniles. … Each of those particular missing persons, whether juvenile or adult, is investigated by our missing person liaison in each of the districts, and also by our downtown detective,” he said.

However, concerns still exist.

“I could see if it was four or three kids, oh, they probably ran away. Thirty, bruh?! All different races, all different nationalities,” argued one Black male critic, who sounded the alarm about the missing children in a TikTok video.

“Thirty missing within the first two weeks of May; as of two weeks ago that number increased to 40 missing youth. Since then, the police department has begun to add greater ‘scrutiny’ to the criteria of what they will report as another ‘missing youth.’ Another consideration is the current pandemic of childhood homelessness, as well as young adults in Cleveland, Ohio. So here on the ground level there is a major concern of unreported cases,” stated Student Minister Quran X of Muhammad Mosque No. 18 in Cleveland.

Of the more than 500,000 missing persons in 2022, 57 percent were White and Hispanic, 39 percent were so-called minority, though Black people make up only 13 percent of America’s total population, according to the Black & Missing Foundation, Inc. Three percent of those missing were unknown, according to the foundation, founded in 2008 by Derrica Wilson and Natalie Wilson. It provides resources, tools and advice to families with a missing loved one; and offers preventative measures for parents to keep their children safe.

Black & Missing Foundation Inc. attributed the disparity in media coverage to children being classified as runaways, therefore no Amber Alerts or national notifications for missing children are issued. Others are labeled as criminals, and then, there’s just a desensitization to the plight of people living in impoverished conditions, where it is believed that crime is a regular part of their lives, according to the Black & Missing Foundation.

El Hajj Khalid Samad and his wife, Raj Khadijah Samad, are part of a group of activists and organized leaders who have worked to challenge threats to the Black community for more than two decades.

They talk to youth about staying safe, taking into consideration that many face mental health issues and various problems within homes, such as molestations, abuse and having to rear themselves, said Mrs. Samad, a former high school teacher.

“There are so many children that are sexually abused in their own homes. I can’t even tell you story after story. It’s horrifying,” she said. “Some children may be rebellious, but others, when they become teenagers, may just run off from bad situations.”

Obviously, some may be kidnapped, but family dynamics tend to give clues, she said. However, any child that’s gone is very concerning and scary, she added.

According to the Black & Missing Foundation Inc., thousands of people are reported missing every year in the United States, and while not every case will get widespread media attention, the coverage of White and minority victims is far from proportionate.

In “The Forgotten Victims of Missing White Woman Syndrome: An Examination of Legal Measures That Contribute to the Lack of Search and Recovery of Missing Black Girls and Women,” a 2019 study brought by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository, researchers compared 19.5 percent—Black missing children cases covered in news media with 33.2 percent—the actual percentage of reported incidents from FBI data. They concluded that racial disparity is prevalent in media because “African American missing children cases are underrepresented in national news compared to their actual rates of incidence.”

Although Black missing children amounted to a shockingly low seven percent of media references, they accounted for 35 percent of the National Crime Information Center’s cases, according to the study, cited Jada Moss, Juris Doctor candidate for the law school, from “Missing Children in National News Coverage: Racial and Gender Representations of Missing Children Cases,” a 2015 study conducted by Seong-Jae Min and John C. Feaster.

“A mid-2000 study conducted by Scripps Howard News Service found that although White children accounted for only 53 percent of the 37,665 cases reported to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, and 54 percent of cases in a study conducted by the U.S. Justice Department, they were covered in 67 percent of The Associated Press’ (AP) missing children news coverage, and 76 percent of CNN’s news coverage,” reported Ms. Moss’s study.

“Conversely, Black children accounted for 23 percent of missing children cases reported to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, and 19 percent of the cases studied by the U.S. Justice Department, but were only represented in 17 percent of AP’s stories and 13 percent of CNN’s stories,” it continued.

“The Forgotten Victims” posits that in order to address the issue that Missing White Woman Syndrome creates, state and federal governments must be willing to implement laws and systems that are structured to address the needs of minorities. To facilitate the drafting and proposal of such reforms, advocacy groups and organizations must lobby and advocate specifically for state and federal programs that will demand that local, state, and federal governments allocate resources to underserved and underrepresented populations.

Places to look include programs that have already been executed and organizations which already have solid bases to serve as models for new programs and overhauls of existing programs, such as the AMBER Alert System, the RILYA Alert System, Help Save The Next Girl, Black & Missing Foundation, Inc., and Peas in Their Pods, Inc., recommended authors.

“The Forgotten Victims” centered on AP and CNN, as they are major sources of print and television news in the U.S., but experts believe its findings reflect reporting practices across the nation’s news media, according to the report.

“I personally do not feel that the media is doing enough, and I’m talking about the media locally and nationally, to address that issue at all. We get it through social media, and to me, it’s scary! It’s like they don’t even care,” Mrs. Samad said.

Mariah Crenshaw is a lead researcher and analyst for Chasing Justice, LLC, a watchdog group that works to expose corruption in politics and police misconduct. She, too, feels law enforcement and media are not doing enough to find the children.

In Ms. Crenshaw’s view, Black people across the country have lost values, practices and a cohesiveness that kept children safe. “Everybody knew each other, looked out for each other. Now, people are hiding, because there’s just gunfire outside,” she said, referring to, for example, a spate of shootings that killed two people and injured 21 in a span of three days, over the Memorial Day weekend, according to news reports.

“I think it’s 37 at last count and it’s very scary, because Cleveland just seems to be like it’s completely out of control,” Ms. Crenshaw said.