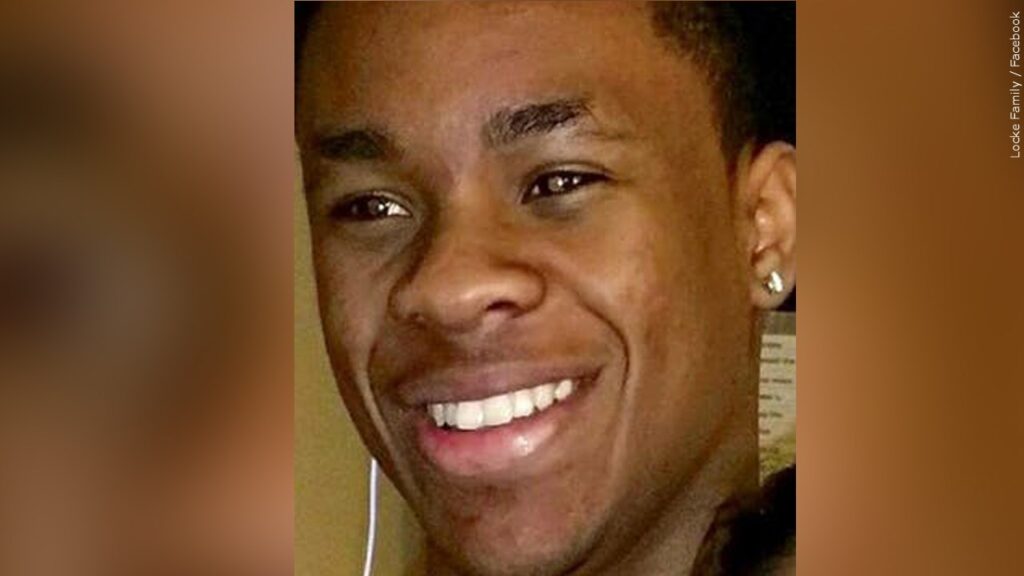

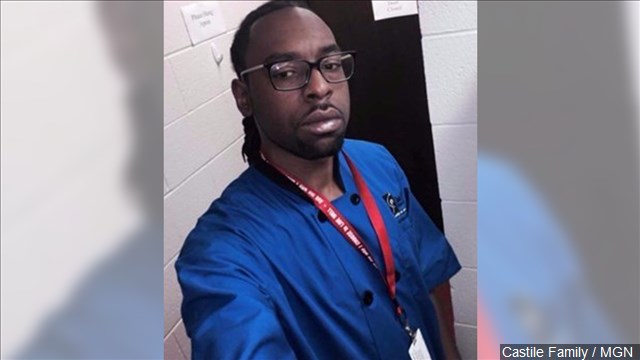

Jamar Clark. Philando Castile. George Floyd. Dolal Idd. Daunte Wright. Winston Boogie Smith. Amir Locke. These seven Black men are more than just names. They were fathers, sons and brothers whose lives were taken by police in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul metropolitan area within the past eight years.

Activists in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and surrounding areas told The Final Call that they have been speaking out against police brutality for years and have seen little to no progress. Now, the U.S. Department of Justice has released findings stating what activists have been saying all along.

“We weren’t really surprised at all because this is what Black folks have been saying forever. These are the things that have been going on with the police. So, I will say that there was a validation, yeah, but we didn’t even really need the validation because we’ve been saying it,” Cynthia Wilson, president of the Minneapolis NAACP, said to The Final Call.

“A lot of it we already knew or had already experienced ourselves, especially those of us who grew up here in Minnesota. We remember police would grab people or hear stories about people getting taken down to the Mississippi River … at night and being beaten,” Trahern Crews, co-founder of Black Lives Matter Minnesota, said. “And just a lot of the brutality in the 80s and the 90s, during the drug wars and stuff like that. So, we already knew it. We just didn’t have cell phones or a police accountability movement like we do to bring it to the forefront.”

Harry “Spike” Moss, who has been fighting against police brutality since 1966, urged the Justice Department to prove it is “here for us” by reopening cases of officers who have a long history of abuse that the DOJ has ignored.

Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke of

the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division.

AP Photo/Abbie Parr

June 16, 2023, the Justice Department, along with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Minnesota, released findings of civil rights violations by the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) and the city of Minneapolis.

The investigation into the police department and the city was opened on April 21, 2021, one day after Derek Chauvin, the killer of George Floyd, was convicted of murder and manslaughter. The Justice Department reviewed thousands of documents, incident files, body-worn camera videos, and city and MPD data and conversed with MPD officers, city employees, mental health providers and community members and local organizations.

The result was a 92-page report accusing the city of Minneapolis and the police department of engaging in a “pattern or practice of conduct that deprives people of their rights under the Constitution and federal law.” Those patterns and practices include: the use of excessive force, including unjustified deadly force and other types of force; unlawful discrimination against Black and Native American people in enforcement activities; the violation of rights of people engaged in protected speech and discrimination against people with behavioral health disabilities when responding to calls for assistance.

The Justice Department also found “persistent deficiencies” in the Minneapolis Police Department’s accountability systems, training, supervision and officer wellness programs.

Examples of violations mentioned in the report, related to use of excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment, include: an off-duty officer firing his gun into a car containing six people within three seconds of getting out of his squad car; officers firing at a man who stabbed himself with a knife;

Officers shooting at moving cars; the use of neck restraints, without warning, on people who committed low-level offenses or posed no threat, such as in the case of George Floyd; the use of tasers in an unreasonable and unsafe manner, such as in the case of an unarmed Black woman who was left bleeding, shaken and jailed for an illegal U-turn; unreasonable takedowns, strikes and use of chemical irritants such as pepper spray;

The failure to render medical aid to people in custody, such as in the case of a diabetic woman who said she needed help, asked for a doctor multiple times and ended up laying on the concrete, barely moving; the failure to intervene when another officer is using unreasonable force and the inadequacies of supervisors in reporting use of force.

Regarding racial discrimination, the Justice Department found that the MPD disproportionately stops Black and Native American people and patrols differently based on the racial composition of the neighborhood; discriminates during stops when deciding who to search and conducts more searches during stops involving Black and Native American people than during stops involving White people who are engaged in similar behavior.

“The findings might be worse because it’s showing not only the patterns and practice of constitution violations, but specifically discriminating against Black and Native community members with specific examples, which I think is something that is not only highly disturbing, but it’s been consistent with what the community has been saying,” Mohamed Ibrahim, deputy director of the Minnesota chapter of Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR-MN), said.

He noted that since the murder of George Floyd, there has not been any meaningful reform or change.

The DOJ report also lists First Amendment rights violations, in particular during protests, against journalists, against people who observe and record the activities of the police department and during stops and calls for service.

“It certainly is a very condemning report as it relates to the police department there in Minnesota. And I think that it brings to mind the history of policing in America, and it shows that the attitudes of the early police departments, which emerged from plantation slave patrols, those attitudes towards Black people and people of color in general, remain up until this day,” Memphis-based Nation of Islam Student Minister Demetric Muhammad, an author and researcher, said to The Final Call.

“But at the same time, it confirms what many grassroots brothers and sisters, those of us who live inside of Black America, have been saying for years, long before these kinds of Department of Justice reports came out, even long before the advent of cell phone video footage,” he added.

“Black people have been clamoring and screaming and sounding the alarm and exclaiming for many years that the enforcement of laws in America are unjust and unfair. And you now see that, through this Department of Justice report, the city of Minneapolis is one of those departments that is egregious, and throughout the report, the term ‘unreasonable’ is continuously used.

Unreasonable use of deadly force and unreasonable use of tasers and unreasonable profiling of Black people and an unreasonable show of negligence,” stated Student Minister Muhammad, author of the book, “How To Police The Black Community: Divine Guidance for Law Enforcement From the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad and the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan.”

The problem of police brutality in Minneapolis is a costly one. Between 2018 and 2022, the city paid over $61 million in 71 claims or lawsuits over police misconduct, according to the DOJ report. So far in 2023, the city has approved additional settlements of over $9 million. Often, money is also dished out due to an officer’s repeated misconduct, such as one officer who had 68 force incidents between February 2012 and June 2016.

The issues of policing in Minneapolis have also caused hundreds of officers to leave the department. As of May 2023, there were 585 sworn MPD officers, down from 892 in 2018, according to the DOJ report.

In a message delivered July 4, 2020, titled “The Criterion,” the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam urged corrupt police to quit.

“Why are the police quitting now? You should all quit. Because if in your presence there you think that you’re going to come into the Black community and do what you’ve been doing, you better quit,” he said.

Activists demands

Activists emphasized the importance of the community keeping pressure on the federal, state and local government in order to see real change.

Ms. Wilson hopes to see accountability tactics that will override police unions to better weed out bad cops. She believes that change can happen now if the police department just followed its own policies and procedures.

“The bad police officers didn’t just happen overnight. So, if you check, I’m sure we would find some form of consistency with them being written up how many times or how many complaints being filed against certain police officers. Those are the ones that you direct your attention to and help, either put them on desks or don’t even put them out on the street. If they’re going to remain somewhere, remain them in a place that they are not going to be effective in the community,” she said.

Mr. Ibrahim said there needs to be adequate reporting and policies that hold bad actors accountable as well as those who are complicit due to their silence. Another solution he mentioned is sending mental health professionals to situations that police are not equipped to deal with.

“We need to actually make sure that we have individuals within the community that are responding to mental health crisis calls and are actually equipped with the necessary training and making sure that they’re not harmed,” he said.

Mr. Moss noted that Black people have always had to rebel in the street “because they knew the courts weren’t going to bring them nothing.” The longtime activist wants the Justice Department to prove it is serious by deterring the opportunity for racist White people to join the police force. “What stops them? Make sure they see themselves being taken out of their beautiful homes in the suburbs all over the state and finally being held accountable for the crimes they committed, that they got away with year after year after year. Make those footsteps, first,” he said.

The fact that Black and Native communities were patrolled differently stood out to Mr. Crews. He mentioned how Minnesota’s racial wealth gap is the third worst in the U.S. and how Hennepin County, which is a part of the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area has been ranked one of the worst places to live in for Black people. The city of Minneapolis and the state of Minnesota need to atone for the harm that they have caused by paying reparations, he said.

“We believe that money should be used to pay reparations to Black Americans who are experiencing police brutality in our streets and in our schools,” he said. Mr. Crews also believes that the Black community needs to come to a consensus about what to do when it comes to policing.

“We want a database of killer cops so cops can’t harm somebody in St. Paul then move to New Jersey or Minneapolis and continue to harm Black people,” he said. “Those are some of the policies that we want to see change. But to make the DOJ do what they’re supposed to do with these findings, it’s going to take the community to keep the pressure on the government.”

Next Steps

Mr. Ibrahim outlined the next steps regarding a possible consent decree mandate. First, he said, there will be a negotiation between the city of Minneapolis and the Department of Justice, in terms of meaningful measures for eradicating racial disparities, racial bias, and racial implications in policing.

“Once this consent decree is negotiated and agreed upon, a judge is going to have to approve of it, as well as there has to be a monitor,” he said. The monitor’s job will be to chart the progress of how close the city and the police department are to achieving their milestones and goals that would be set by the consent decree.

Mr. Ibrahim noted that if the monitor is unequipped or unable to do their job, then nothing is going to change. “Now, if you have a monitor that’s actually doing their job and is actually keeping up and looking at the data and making sure the reporting is right and getting input from the community to make sure that the police department or the city is actually ringing true to their promises that they made within the consent decree, then that changes the ballgame completely,” he said.

“And one way that we have seen police departments subvert this consent decree is by making sure that there’s an ineffective monitor that is a part of this process of holding them accountable,” he added. “So, I think for us, it is important to have community members be a part of the process in terms of selecting the monitor, but ultimately now, it just comes down to, can there be an effective monitor that will then bring issues to light that then later on the Justice Department can hold the city accountable for.”

“If they don’t change, we’re probably headed to another rebellion,” Mr. Moss said. “Minnesota Blacks don’t believe they’ll ever receive justice. They don’t believe it.”

There have been several police departments around the country under consent decrees over the years including, Chicago, Los Angeles, Cleveland, Memphis, New Orleans, Baltimore and several others. Observers have noted that while some have ushered in reform credited with bringing some necessary reforms in some areas but criticized by others as ineffective.

Student Minister Muhammad said Black people have to become organized and have to get involved in every aspect of the cities and towns they live in. “We cannot have a mind (and) attitude that causes us to stand on the sidelines as spectators and allow the conditions in our communities to continue to deteriorate,” he said.

He mentioned models of living that are worthy of consideration by the Black community, such as, how many immigrant communities live.

“You have communities that live and are situated inside regular America, but they carve out their communities, and they have something of a separate existence in an open and free society. But these immigrant communities, sometimes called by scholars ‘ethnic enclaves,’ are safe havens for people of a similar ethnic background, similar faith tradition, similar spoken language, and they are able to live, work, play, raise their children in neighborhoods that by and large, they control and they regulate,” he said.

“Our neighborhoods are not controlled by us. The businesses are not owned by us. The institutions are not run by us. So once again, we see that the pain of Black life in America is causing us to take another look at the ideas that have been advanced by the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad,” he said, referring to the proposed solution of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, the Eternal Leader of the Nation of Islam, which is the separation between Black and White.

“Because we are now decades into the experiment of integration, and many of the metrics that measure the quality of life of Blacks are worse today than they were during the days of segregation,” he added. “It’s time for us to organize and take control of our own community.”