by Tingba Muhammad —Guest Columnist—

In part one of this article published in The Final Call Vol. 42 No. 35, we exposed the truth of why Jewish leaders and Jewish organizations ignored the death of Dr. Martin Luther King’s right-hand man, Harry Belafonte. Here is Part 2.

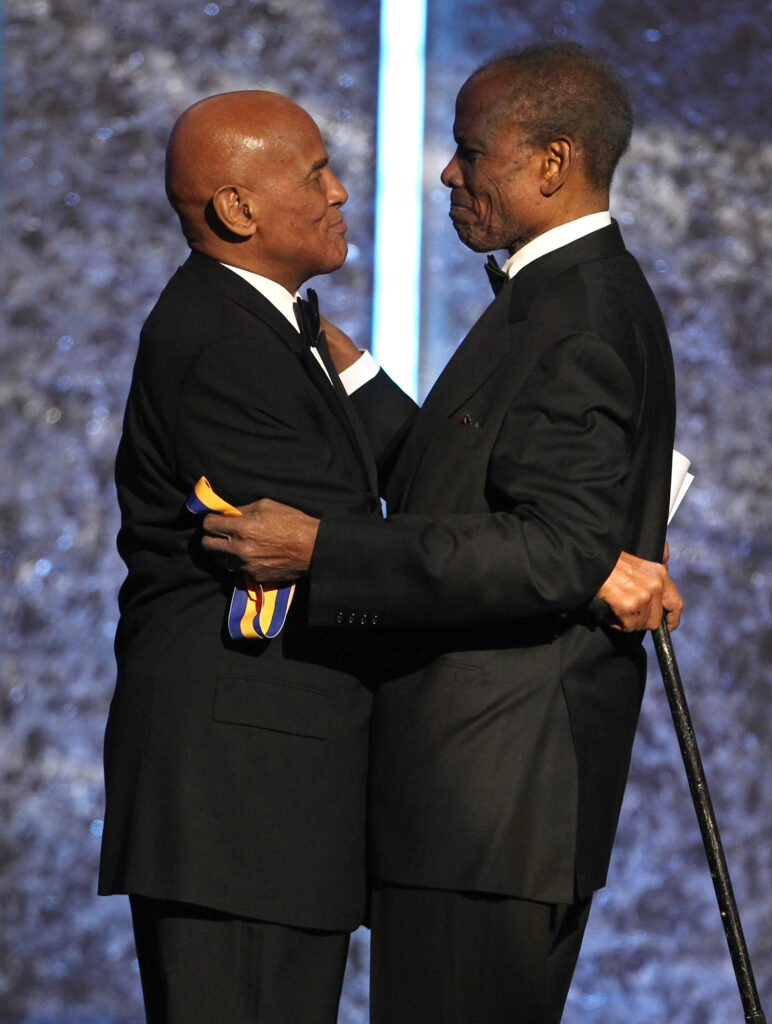

After the murder of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King and the deliberate stalling of the civil rights movement, Harry Belafonte’s international activism became more pronounced. He openly criticized U.S. foreign policy and outreached to “third world” governments and leaders that America and the West had despoiled, opening dialogue with Cuba, South Africa, the Caribbean nations, and even praising peace initiatives by the Soviet Union. Belafonte joined Sidney Poitier and others to fund a scholarship program in Kenya that allowed a young Kenyan student to study in Hawaii, where he met a young White woman and produced a child that would become the first Black president of the United States, Barack Obama.

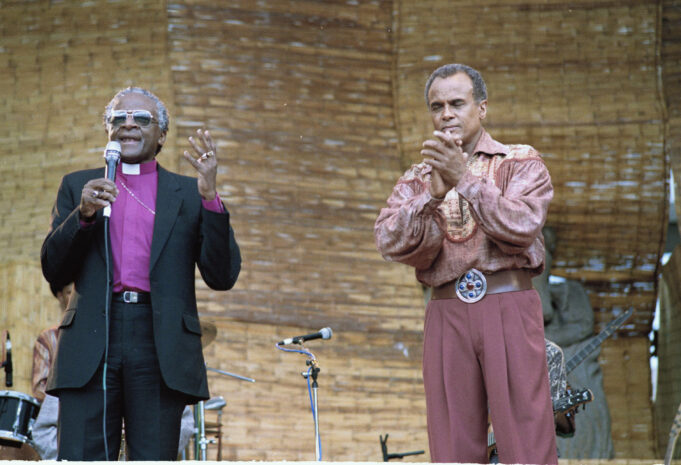

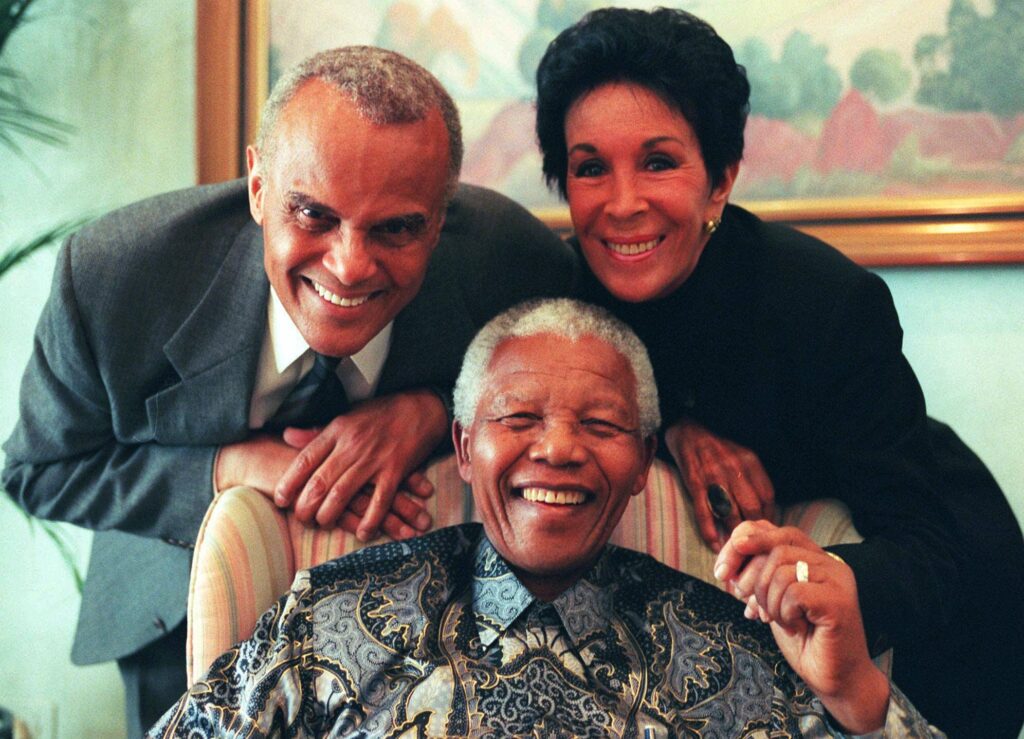

Belafonte had clearly evolved from a singer of popular Jewish melodies to an outspoken activist who recognized that the same kind of apartheid system he fought beside Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu to overthrow in South Africa, was now entrenched in the “State of Israel” against the Palestinian people. Upon Mandela’s release from prison in 1990, Belafonte organized a hero’s welcome for him in an eight-city tour around America.

And in remarks to a Jewish group, Belafonte recounted the U.S. State Department’s warning to him that he said: “struck me very, very deeply.” They informed him that “there are segments of the Jewish community that find his [Mandela’s] presence in this country unwelcome, and they will make their feelings heard, and we are concerned about that because one group in particular has been noted for its willingness to do violence.”

Belafonte could have possibly recalled that six years earlier, Jews had deliberately created a violent atmosphere around presidential candidate Rev. Jesse Jackson, actually calling for him to be “ruined” in a New York Times advertisement—a volatile situation that the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan publicly addressed and that necessitated the Nation of Islam providing security for Jackson and his family.

By 2017, Belafonte joined Angela Davis, Alice Walker, and many other activists of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement in signing an open letter appealing to NFL players to boycott a “propaganda trip organized by the Israeli government that aims to prevent players from seeing the experience of Palestinians living under military occupation.”

Belafonte would recall that it was just this issue of Jewish–Israeli oppression of Palestinians that triggered the most jarring convulsions in the alleged Black–Jewish alliance. Jewish money backing the civil rights movement dried up when Blacks began discussing the commonality of the Black-American and Palestinian struggles. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter’s U.N. ambassador, Andrew Young, was summarily fired for simply meeting with a Palestinian leader;

Jesse Jackson was attacked brutally in 1984 for suggesting that his candidacy for president would be fair to the Palestinian people; and Minister Farrakhan was called a “Black Hitler” for defending Jackson on the Palestinian issue. So, Harry Belafonte’s successful effort to block Israel’s attempt to make Black NFL players “ambassadors of goodwill for Israel” was a decisive setback. In 2017 the Guardian reported it this way: “The Israeli government has suffered an embarrassing blow after it emerged that only five of 11 NFL players turned up for an all-expenses-paid PR trip organized to improve Israel’s image.”

Belafonte’s Early Black–Jewish Battles

None of the commemorative reflections of Harry Belafonte’s admirers took into account his own Black–Jewish memories, which may have crystalized for him later in his career. Such as when in June of 1962 he performed at an Atlanta fundraiser for Dr. King for a racially integrated audience of 5,000. Belafonte, Dr. King and his wife, Coretta, and several members of their entourage attempted to eat lunch at Leb’s Restaurant—one of nine owned by a Jewish racist named Charles Lebedin—only to be turned away.

When Belafonte returned to Leb’s the following morning, he was again refused service. Aware of the bad press his racism had caused, “Leb” played the “Jewish suffering” card: “I know how it feels to be discriminated against, and I’m a great admirer of Belafonte. But I can’t integrate my restaurant because the others won’t.”

Lebedin’s allusion to his Jewishness only further infuriated Belafonte, who pointed out that there were many integrated restaurants in Atlanta. “I’m not impressed with Mr. Leb’s Jewishness. I am married to a Jew.” Dr. King called the incident “a tragedy for Atlanta” and threatened “a full-scale sit-in movement” if Lebedin’s segregationist policy was not reformed.

In fact, Lebedin, who called himself “a proud Jew” with many Jewish customers, doubled down and a month later Blacks “staged a three-hour stand-in” at a Leb’s fundraiser for Atlanta’s Jewish Home for the Aged for which advertisements offered, “Come One Come All!” Lebedin said he was “not going to serve them [Blacks] today or any other day.”

This only escalated mass demonstrations at Leb’s and according to the Atlanta Constitution, Lebedin “hired goons to keep integrators out,” and Ku Klux Klansmen stood with Lebedin to enforce Jim Crow law. It was his snub of Belafonte and King that put the Jewish segregationist at the center of civil rights protests and exposed Atlanta’s Jews as civil rights hypocrites.

More than a hundred demonstrators were arrested attempting to eat at Lebedin’s restaurants, but it was he that complained: “I’m very bitter and hurt. I’m a very strong segregationist now. … The Negroes have made me that way.” Lebedin and his restaurant manager stood outside a dinner honoring King’s win of the Nobel Peace Prize, shouting: “What a hullabaloo over a nigger. … I ought to give him a piece of my fist.”

Belafonte’s experience with Jewish Hollywood was no less traumatic, and he recounted his frustration at its treatment of him: “I put script after script before people who just rejected them out of hand, and I just said there’s no point in trying to change this monster. They would not listen to my gods.”

In 1960, Belafonte received an Emmy for a television special he did for the “Revlon Hour,” called “Tonight with Belafonte.” He then describes what that did for his career:

“‘Now I get called by [Revlon owner] Charlie Revson to have a meeting,’ he told me. ‘Would I come alone? I can’t wait—I’m figuring he wants to give me half the company, or something. So, we’re having lunch in his private dining room, and he’s saying, ‘As a Jew in Jersey City, I understand oppression—da, da, da, da—but we have to talk about the show. Good ratings. Good reviews. Very nice. But we’re getting some response that says you should do it all Black. If you could just take all the White people out … .’

I couldn’t believe it. And I said, ‘Mr. Revson, let me tell you something. If you’d asked me to put on a flowery shirt and sing more calypso tunes, and dance more, because that’s what White people would like, I would consider it. But what you’ve asked me to do—there’s no way to square it. I cannot become resegregated.’ He said, ‘O.K.’ Four o’clock that afternoon, I had a check for eight hundred thousand dollars ($8 million dollars in today’s money)]. Charlie Revson said, “Goodbye. You’re off the air.’”

As his thinking evolved, Belafonte moved decisively away from political and social integrationism and publicly supported freedom and independence efforts that earned him the ire of Jewish leadership. Certainly, Belafonte’s incredible career as an entertainer and an activist offered him a wealth of experiences and interactions with Jews that ordinary Black Americans had no chance of having. His unique presence at the very heart of the civil rights movement makes his criticism of it especially poignant and instructive.

Beyond the plaudits and platitudes, Harry Belafonte’s history with Jews was rife with conflict and controversy, which we now know was the fate of every single Black leader of significance going back centuries—all had bitter run-ins with the Jewish leaders of their day. From the hunters of African maroons that escaped from Jewish plantations in 17th-century Surinam, to the Jews who helped hunt down Nat Turner, to the Jewish attacks on Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad, Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, and now the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, all of whom felt the lash of the false charge of “anti-Semitism.” In his passing, we can now see that Harry Belafonte has joined that extraordinary and blessed Black fraternity.

In expressing their grief and their honor for the life and legend of Harry Belafonte, Blacks embrace his life’s evolutionary journey and the lessons that he left for us. His “supreme integrity, honesty, and commitment,” as Minister Farrakhan affirmed, must never be forgotten. The monumental act of Jewish disrespect for Harry Belafonte only increases his legend and illuminates his legacy.

Tingba Muhammad is a researcher and citizen of the Nation of Islam. Visit the N.O.I. Research Group online at www.noirg.org.