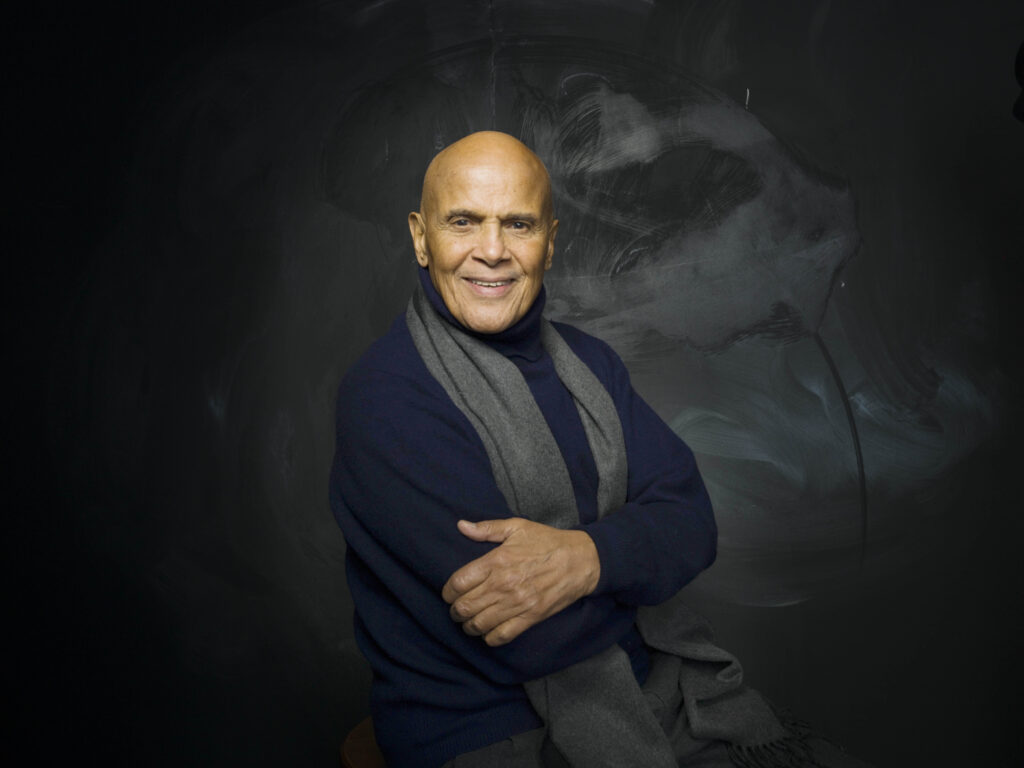

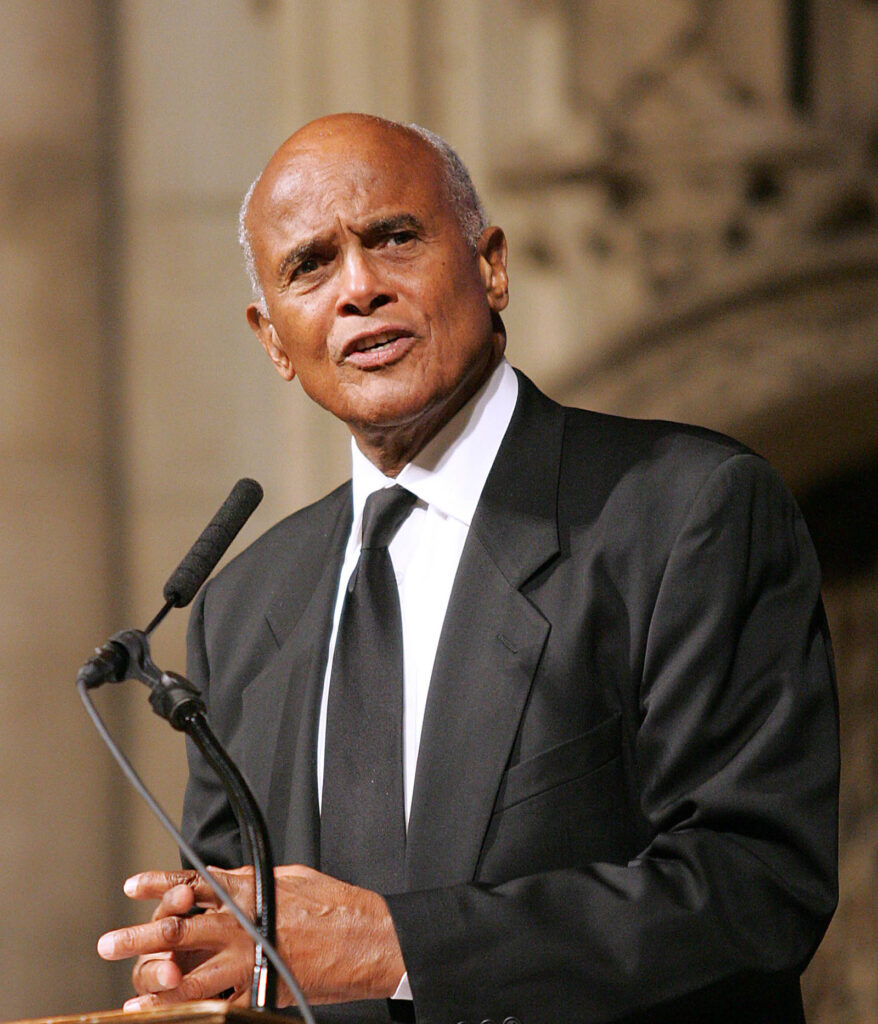

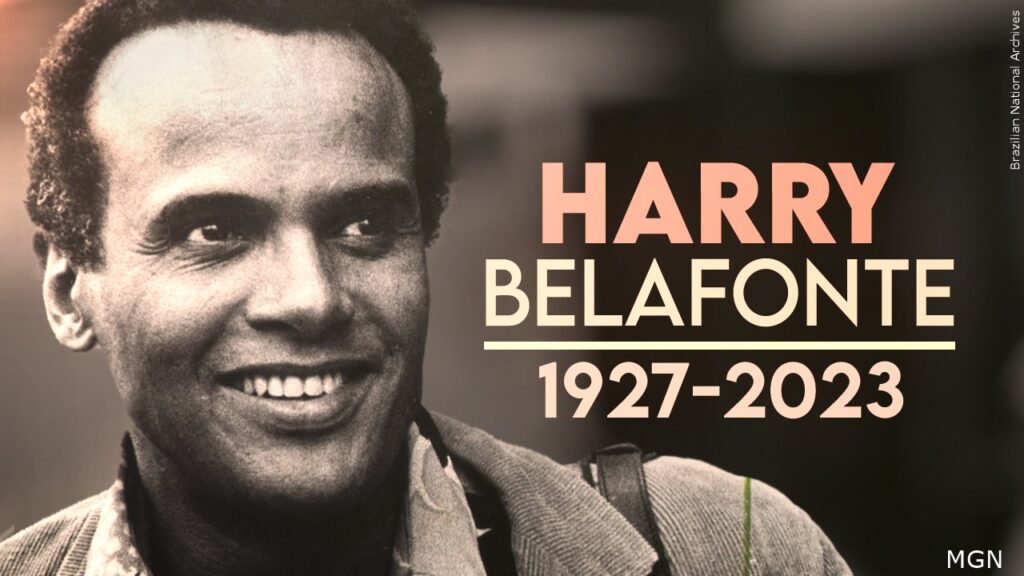

While all people are granted the gift of life, some only exist, and others contribute to the experience of life. The list of those who gave back to life would be woefully incomplete absent the name of Harry Belafonte, the activist, humanitarian, actor, and singer. He died on April 25 of congestive heart failure at his home in New York City. He was 96 years old.

The life and works of Mr. Belafonte are being celebrated by people across the world. He is being memorialized as a star of the art world; but also as one who used his fame, talent, and resources as a tenacious fighter, comrade, and advocate for the souls of Black folks and suffering people worldwide. A cross-generation of leaders, admirers and everyday people are celebrating “Mr. B” as he is also affectionally called.

“I love that man, very, very much and I’m deeply saddened by his passing,” said the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam, in a special tribute to his friend, in remarks on Roland Martin Unfiltered.

Both men have roots in Jamaica, West Indies, were born in New York City to Caribbean parents, and were young contemporaries in the world of Calypso music; and dedicated decades of struggle for human uplift, freedom, and justice.

“So, my brother is gone. But I celebrate that man … not just Calypso,” said Minister Farrakhan. “He was a man of supreme integrity, honesty, commitment. That’s the Harry Belafonte that I know,” the Minister stated. (See a special 8-page insert in this edition to read Minister Farrakhan’s message in its entirety.)

Others remembered Mr. Belafonte for his unwavering spirit of struggle and unselfishness.

“He was a consistent, gentle giant for justice,” said Father Michael Pfleger, senior pastor of St. Sabina Church in Chicago. The activist priest remembered “Mr. B” as “bold and unashamed” about his commitment, beliefs, fights, and someone fearless about the costs. The sacrifice was unimportant because he accepted the price, said Father Pfleger.

“If I had to use one word to characterize Harry Belafonte, he was fearless in the face of racism, imperialism, and oppression,” said Dr. Benjamin Chavis, president of the National Black Publishers Association. Dr. Chavis hopes the passing of Mr. Belafonte will cause Black people to “rededicate” themselves to keep his freedom-fighting spirit alive.

“I knew him when he was singing Calypso … but he morphed into an amazing freedom fighter,” said Cora Masters-Barry, former first lady of Washington, D.C., and wife of the late Mayor Marion Barry. Mr. Barry was the first chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) that Mr. Belafonte funded to get started in the early 1960s.

Ms. Masters-Barry told The Final Call the most important act by Mr. Belafonte was his impact on younger activists on the battlefield today like Tamika Mallory, Linda Sarsour, Carmen Diaz-Jordan, and others.

“He took his wisdom … knowledge … courage … and infused it into the generations behind him, and for that, he will live forever,” said Ms. Masters-Barry.

A born freedom fighter

Any belief that Mr. Belafonte was an actor turned activist is a misnomer. “I was an activist who became an artist, and my activism really started the day of my birth,” Mr. Belafonte told PBS in a 2011 interview. He credited his mother and what he experienced growing up in Harlem, on 145th, and St. Nicholas, and in Jamaica (West Indies).

He was born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. March 1, 1927, in Harlem, N.Y., the oldest son of West Indian immigrants. His mother, Melvine, worked as a dressmaker and a house cleaner, and his father was a cook on merchant ships. He was a young child when his parents divorced.

“My mother was overwhelmed by America,” he told PBS. “She came here with hopes and ambitions that were never fulfilled,” he added.

Mr. Belafonte said his mother was bringing children into the world at an age that was much too young and although she stayed the course and treated her children with great dignity and care, her life circumstances overwhelmed her. She moved them to her native Jamaica to be raised by the village and family she grew up in.

There, he saw firsthand the oppression of Black life by British colonialism which left a lasting impression on him. The seed was planted for what became his lifetime of service as a change agent for Black and oppressed people across the planet.

When Mr. Belafonte returned to Harlem in 1939 he said he was exposed to an active movement, a global struggle, and talk about democracy in America and combating White supremacy.

“We were listening to people like Paul Robeson and Dr. (W.E. B.) Dubois and others, speaking about the Black relationship to this world struggle,” Mr. Belafonte explained.

On any day in Harlem at the time, it was common to see Mr. Robeson, boxing champion Joe Louis, or Dr. DuBois. “Our role models were always there. And by the time I came upon the idea of being an artist, I brought with me this mission of activism,” Mr. Belafonte recalled.

In the arts, he saw a space where theater could be used as a powerful social and political tool.

A long stellar career

By 1944 Mr. Belafonte dropped out of George Washington High School in Upper Manhattan and enlisted in the Navy and served in World War II. Afterward, he worked several odd jobs before finding his calling to the arts, after attending a performance of the American Negro Theater.

He was trained at the New York Dramatic Workshop where his classmates included Marlon Brando, Walter Matthau, Bea Arthur, and Sidney Poitier.

Mr. Belafonte performed “traditional,” “world music,” “folk,” “calypso,” and “protest songs,” along with his acting career that spanned over seven decades.

As a talent, he popularized the Caribbean genre of Calypso to U.S. audiences and performed folk music in nightclubs, theaters, and on television and records. He appeared in the Broadway revues “John Murray Anderson’s Almanac” and “Three for Tonight.” He owned his own music publishing firm and film production company. As a multi-award-winning artist, Mr. Belafonte has won Grammy awards, an Emmy Award, Tony Award, Donaldson Award, Show Business Award, and a Diners’ Club Award.

On film, he played a school principal opposite Dorothy Dandridge in his first movie, “Bright Road” in 1953. They then acted in “Carmen Jones,” a film adaptation of Oscar Hammerstein II’s contemporary, Black Broadway version of Bizet’s opera “Carmen.” Mr. Belafonte received an Academy Award nomination for his character Joe, a soldier who falls for Carmen, played by Ms. Dandridge. The movie made him a star.

Soon after he released “Calypso” in 1956, a music album featuring Caribbean folk music, “The Banana Boat Song (Day-O)” became the signature song. Though an audience “call and response” favorite, the song was a serious labor song. “That song is a way of life,” Mr. Belafonte told The New York Times. “It’s a song about my father, my mother, my uncles, the men and women who toil in the banana fields, the cane fields of Jamaica.”

It topped the Billboard charts for 31 weeks and made him the first platinum-selling recording artist in the industry’s history, with sales exceeding a million copies. The song helped fuel Mr. Belafonte’s bridging art with social justice.

In the 1970s, Mr. Belafonte starred alongside another fellow son of the Caribbean, Sidney Poitier, in “Buck and the Preacher” and “Uptown Saturday Night.” Later films included “White Man’s Burden” (1995), and “Kansas City” (1996). He also appeared in 2006’s “Bobby,” a film about the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, and appeared in Spike Lee’s 2018 film, “BlacKkKlansman,” where he portrays an elder schooling young activists about America’s sordid history.

Mr. Belafonte’s memoir “My Song” was released in October 2011. In conjunction with the book release, HBO debuted the critically acclaimed bio-documentary “Sing Your Song,” directed by Susanne Rostock. The film chronicles his life through his own words, eyewitness accounts, FBI files, and archival footage.

Supported civil and human rights

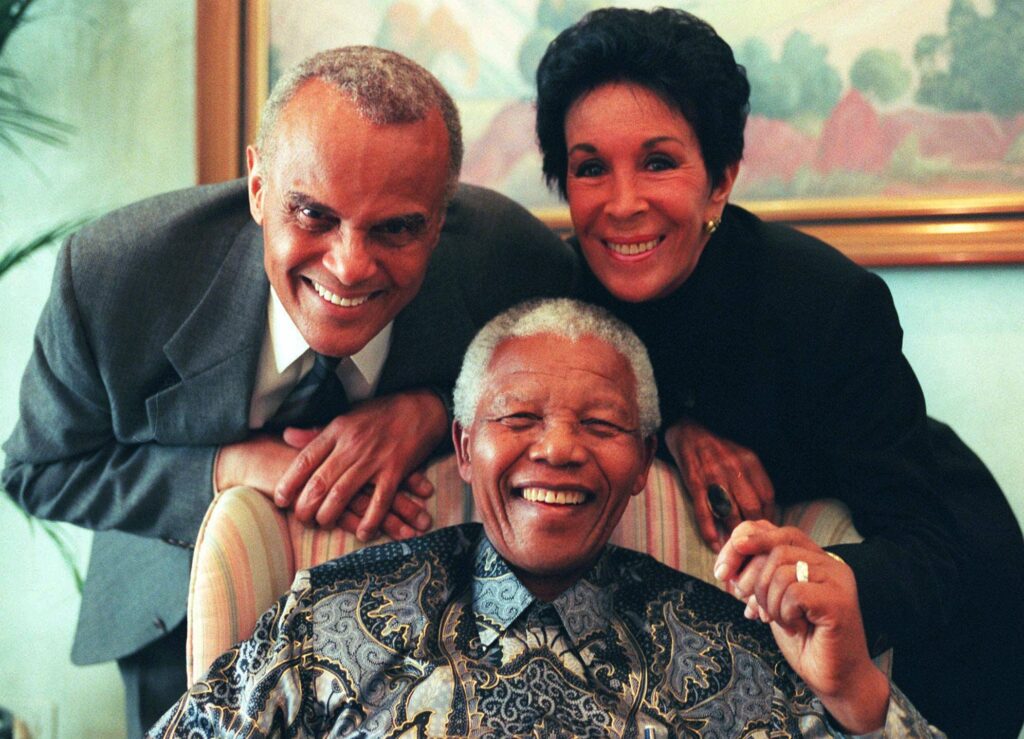

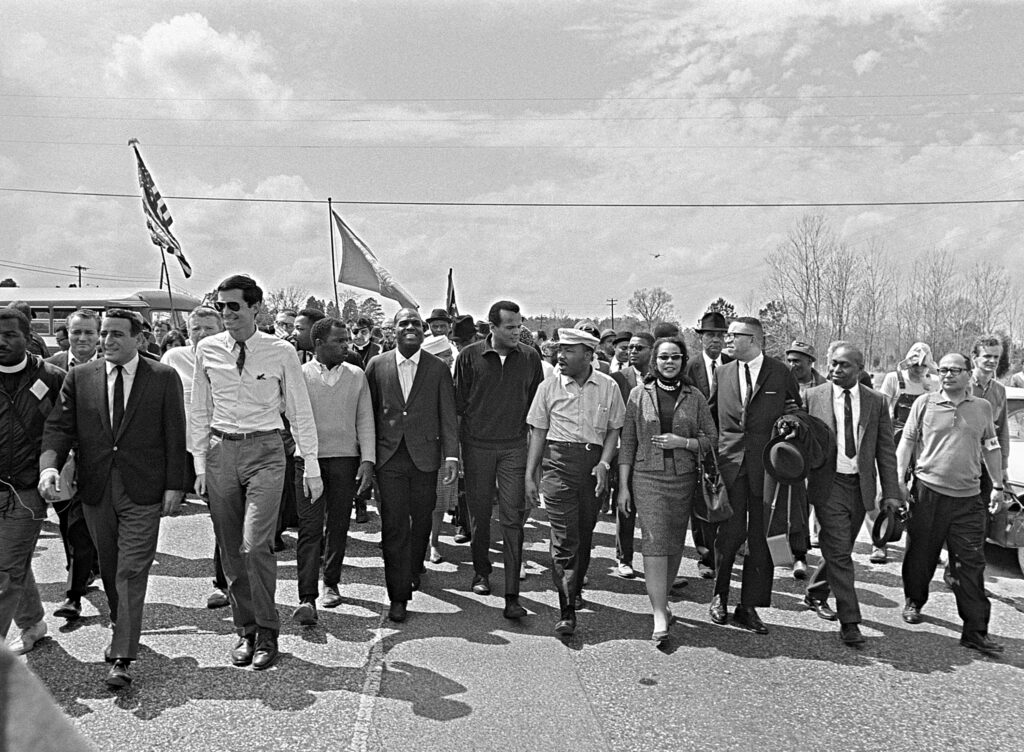

Mr. Belafonte used his celebrity stature to bring other artists like Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis Jr, Marlon Brando, and others to help support and stand with the justice movement. From funding civil rights organizations like Dr. Martin Luther King’s, Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), or the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the 1960s to lending his stature to international movements for justice like the anti-apartheid struggle to abolish White minority rule in South Africa and freeing incarcerated leaders like Nelson Mandela, Mr. Belafonte was on deck.

His presence was that of a strategist and a moral compass countering the immoral posture of a nation stained with the blood of its most marginalized. “Mr. B” was a voice for the voiceless.

While Dr. King was held in a Birmingham jail, Mr. Belafonte reportedly raised $50,000, allowing the campaign to proceed.

Former United Nations Ambassador and Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young, a member of Dr. King’s inner circle, described Mr. Belafonte as a major force in the movement and considered by Dr. King a confidante and friend.

Mr. Belafonte’s generosity and loyalty compelled him to invest and call on others in the arts to support the movement. He looked out for Dr. King and his family, even after the leader’s assassination in 1968. Mr. Belafonte secured a $100,000 insurance policy on Dr. King’s life—after being rejected by insurance companies for a one million dollar policy he sought. It was reportedly the only money Coretta Scott King had after her husband’s death.

Mr. Young told The Final Call it was Harry Belafonte that pushed him into making his first run for Congress. He recalled a meeting Dr. King had that included Mr. Belafonte, John Conyers of Detroit, and Richard Hatcher of Gary, Indiana. Dr. King said they had to take the movement’s energy from the streets into politics. Mr. Conyers eventually became a representative in Congress and Mr. Hatcher became the first Black mayor of Gary.

“That was the last conversation we had, in New York,” said Mr. Young, before Dr. King traveled to Memphis the next day fulfilling a promise to march with striking sanitation workers. “That was the last marching orders … that we had to get in the elective politics, if we were going to advance the causes of people,” recalled Mr. Young.

Dr. King was killed in Memphis on April 4, 1968, during an explosive era of assassinations that included Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, and a dozen others that nobody knew about.

People were nervous about running for politics, said Mr. Young. “He didn’t ask me,” recalled Mr. Young, speaking about Mr. Belafonte. “He just called his wife and said: ‘we need to raise some money… Andy’s running for Congress.’”

When Mr. Young tried to reject the notion, Mr. Belafonte with his signature drive said, “‘But you sat here with Dr. King and everybody else and agreed,’” recalled Mr. Young. “I said: “But nobody wants to run.’ He said, ‘but that means you have to run.’ And that’s why I ended up running for Congress,” shared Mr. Young.

After the volatile 1960s Mr. Belafonte continued supporting causes worldwide. “He wasn’t just an actor playing politics. He was committed to making the world more like God’s kingdom,” added Mr. Young.

Most entertainers who discover God has blessed them with talent get so egotistically involved with what they do, they forget about the masses of the people, said Rev. Charles Steele, who now leads the SCLC. “Harry Belafonte wasn’t like that; he was concerned about justice and equality for all God’s children.”

He supported Dr. King financially because he knew what Dr. King was confronted with in terms of needed resources and stepped up. That was his legacy in the movement and internationally. “He was internationally involved with resolving issues … not only civil rights, but human rights,” said Rev. Steele.

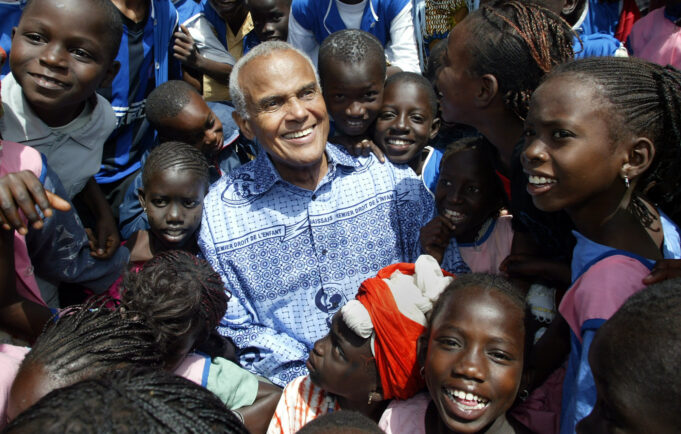

History has documented Mr. Belafonte’s impact on the global stage, from fighting the scourge of HIV-AIDS and combating hunger in Africa, such as organizing 45 top artists to sing “We are the World” which raised tens of millions of dollars for Ethiopia’s famine relief.

The magnitude of Mr. Belafonte’s contribution is huge and still in motion because even as a revered elder in his 90s, he never sat down on the urgency of now. Some felt that Mr. Belafonte became more radical as he got older, or that radicalness has always existed.

A critic of errant U.S. foreign policy and bridging art and activism

Like Paul Robeson, he was an internationalist who stood strong on an anti-imperialist position whether it was around South Africa, Haiti, Cuba, Venezuela, or Iraq. In 2006, he stood against the United States’ illegal invasion of Iraq and unequivocally called President George W. Bush “the greatest terrorist in the world” for launching the war.

Never one to mince words, Mr. Belafonte referred to Bush administration secretaries of state, Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice as “house slaves” who were “serving those who continue to design our oppression.” In response to the expected clap back of his words, he said: “Bring it on. Dissent is central to any democracy.” There is no doubt that Mr. Belafonte’s name will outlive the civilization and times he worked to better.

Mr. Belafonte also embodied the ethos of his mentor Paul Robeson that “artists are gatekeepers of truth.” Through bridging activism and the arts, Mr. Belafonte amplified voices of struggle in the U.S., Africa, and the Caribbean. He supported politically exiled artists like South African singer Mariam Makeba and jazz trumpeter Hugh Masekela. In 2013 the late trumpeter told NPR that Mr. Belafonte, along with Ms. Makeba, paid for his education at the Manhattan School of Music.

It was perhaps more widely known that Mr. Belafonte’s aid of Ms. Makeba, known as “Mama Africa,” whom he first met in London in 1958, he helped propel her to global audiences, while also raising awareness about the repression under apartheid in South Africa. Together, they won a Grammy for Best Folk Recording for their 1965 album, “An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba.”

Passing it forward: From Robeson to Belafonte and beyond

In the tradition of the late actor, singer and human rights defender Paul Robeson, “Mr. B” moved in a similar way and continued to pass it forward to the current generation of artists and change agents. Mr. Belafonte was mentored by Mr. Robeson, whom himself used his celebrity on behalf of—not only Black liberation in the United States—but human upliftment worldwide.

Among contemporary artists, Mr. Belafonte was a respected and noncompromising voice for accountability, said Davey D, a journalist, and hip-hop activist. “He was a real one … I mean he was really ‘real,’” Davey D told The Final Call, about Mr. Belafonte’s commitment. “His impact extends like seven decades; in each decade, he had an impact.”

For this generation, the hip-hop scholar said it should never be forgotten that Mr. Belafonte was one of the first elders to invest in hip-hop, such as producing the 1984 film “Beat Street,” about the early roots of hip-hop culture. Mr. Belafonte mentored artists like Usher, Common, and Donald Glover, (aka ‘Childish Gambino’) as well as artists/activists Talib Kweli, Mysonne, Tef Poe from St. Louis and Jasiri X from Pittsburgh.

In 2013, he initiated Sankofa.org headed by his daughter Gina Belafonte to facilitate the intersectionality of the arts and activism. Sankofa educates, motivates, and activates artists and allies in service of grassroots movements and equitable change. It allows artists to use their platforms and creative gifts to inspire action on the pressing issues of the day.

Abdul Malik Sayyid Muhammad, Western Regional Student Minister of the Nation of Islam, based in Los Angeles, met Harry Belafonte at an event hosted by gang intervention group 2nd Call in 2010.

“I remember having maybe about 30-40 gang members in a room that were having issues and seeing Harry Belafonte at the table and watching how he was able to be in an environment like that without thinking that he was ‘better.’ He was just so calm and so into what the brothers were saying,” he recalled. “I was just blown away, because most people are not comfortable in that environment, particularly civil rights leaders who are not used to basically dealing with conflict within our own culture.”

Harry Belafonte’s presence made the brothers feel good, Student Minister Malik Sayyid Muhammad described, and they started calling him “Elder Homie.” They resolved about 10 conflicts that day, he said.

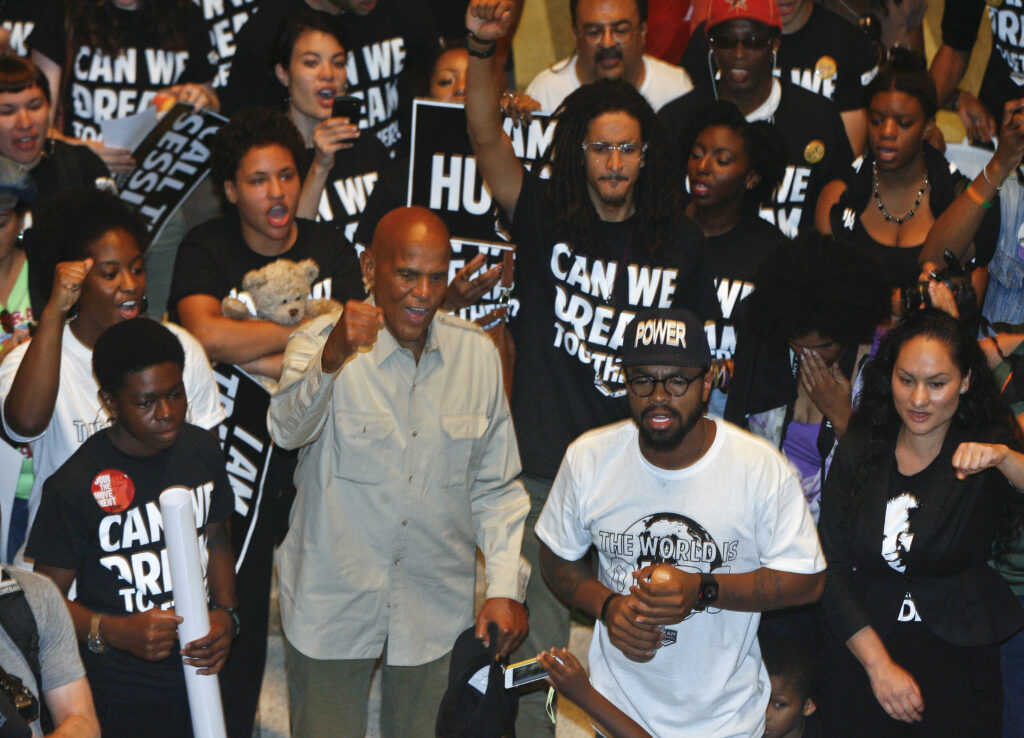

Mr. B remained invested in this generation through “The Gatherings for Justice,” a space where social justice work can transpire, and where he encouraged artists and activists to unite and push the envelope for change. The group was founded in 2005 after he witnessed Pinellas County, Florida, police handcuffing and arresting five-year-old Ja’eisha Scott in her kindergarten class. An act that sparked nationwide outrage.

Carmen Perez-Jordan, a mentee of Mr. Belafonte and president/CEO of “The Gathering for Justice” was one of the young people brought to the table to work with Mr. Belafonte two decades ago. She described “Mr. B” as “an inspiration,” “forward thinker” and “giant of a man,” who deeply cared about Black people, civil rights, liberation, women, and children.

“I’ve met many people around the world … civil rights leaders … leaders from different countries … Mr. Belafonte was an exceptional human being, whose brilliance and visionary approach were actually truly unparalleled,” she said.

In his vast wisdom as a leader, Mr. Belafonte always exposed lessons of the movement and introduced her to people from different walks of life and diverse backgrounds. He felt it was important for those currently in the movement to understand “there’s a lane for each of us” in building community, she explained.

Ms. Perez-Jordan observed that although Mr. Belafonte was clear about the global impact of U.S. policies on other countries and perceived through intergenerational, intercultural, historical, and international lenses: “He always reminded me to never forget my roots,” she said.

“His brilliance and knowledge gave us the blueprint to organize on many scales, keeping our message potent, but organizing for the masses,” Ms. Perez-Jordan said.

In keeping with Mr. B’s legacy, she’s committed to passing it forward and teaching the young people sitting at her feet to continue his legacy at “The Gathering for Justice.”

Hundreds of people joined “The Gathering for Justice” to celebrate the memory of Harry Belafonte at New York’s Lincoln Center on April 26 with speeches and a sing-along of “Mr. Belefonte’s” “Day-O” and “We are the World.”

He put it all on the line

As consequential as Mr. Belafonte became in life, like his mentor Paul Robeson, he paid a price for standing up in a country that persecutes those who refuse to toe the line. He put his life and career on the line and pushed the same standard on younger activists and celebrities. Harry Belafonte was a rare celebrity.

It is a “significant loss,” Dr. Gerald Horne, professor of history at the University of Houston, told The Final Call. He said contemporary scholars should study Mr. Belafonte’s life and extract the lessons necessary for upcoming generations to learn.

“Most celebrities do not find it necessary to get involved in progressive politics,” said Dr. Horne. “Belafonte found it mandatory,” he added.

“May Allah be pleased with our Brother and accept his great contribution to the freedom of our people,” said Nation of Islam Student Minister Jamil Muhammad, host of “Yardbird Sweets” on WPFW in Washington, D.C. “Harry Belafonte was a human being of towering principles … for that I loved him,” said Jamil Muhammad, describing him as the kind of brother who would not jump over brotherhood with his fellow Black man to identify with other folks, who have no clue about the struggle of Black people for freedom.

For Harry Belafonte, there was no stopping, until the goal of human correctness, justice and equality was achieved.

“I’ve always looked at the world and thought what can I do next? Where do we go from here? How can we fix it? And that’s still how I look at the world because there is so much to be done,” Mr. Belafonte once remarked.

“The whole world is caught in human suffering. And those who professed about making change have not come up with answers. We have failed in terms of the moral side. We have to do more,” he said.

Mr. Belafonte was married to Marguerite Byrd between 1948 and 1957, Julie Robinson from 1957 to 2004, and Pamela Frank since 2008. He is survived by his wife, Pamela, four children, two stepchildren, and eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Anisah Muhammad contributed to this report.