Every year, tens of millions of people in the United States struggle with getting access to food that would allow them to live a balanced, healthy life. Increasingly more people are turning to food banks and community programs for assistance.

As inflation squeezed family budgets, food insecurity increased between 2021 and 2022, a report by Urban Institute found. The report, co-authored by Kassandra Martinchek, Poonam Gupta, Michael Karpman and Dulce Gonzalez, analyzed data from the Urban Institute’s annual Well-Being and Basic Needs Survey. More than 7,500 adults between the ages of 18 and 64 were surveyed.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines food insecurity as a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food. Food insecurity leads to hunger: “prolonged, involuntary lack of food” that “results in discomfort, illness, weakness, or pain that goes beyond the usual uneasy sensation.” More than 34 million people, including nine million children, in the United States are food insecure, according to the USDA.

Americans are experiencing a 40-year high inflation, as food prices increased by 10.4 percent between December 2021 and December 2022. The Urban Institute report described the increase as “the highest rise in decades.” The rise in food prices, along with the increase in gas prices during the summer of 2022 and the expiration of federal and state aid, has led to families finding it increasingly difficult to afford food and other basic needs. The report was released March 21.

Along with the New Year came the expiration of increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. Families who were receiving $95 to $250 no longer had extra money for groceries to rely on.

Elisabeth Omilami, CEO of the Atlanta-based organization Hosea Helps, described the carloads of people who come to the organization’s weekly food giveaways.

“It used to be maybe 100 families a week. Now, it’s almost triple that. And then we also have requests coming in from certain schools, districts, certain churches, apartment complexes, asking for a distribution of food,” she said.

Despite partnerships with HelloFresh, Kroger, Publix, Hormel and local farmers, the surge in need has caused the organization to experience challenges in keeping their inventory intact.

Racial disparities

The Urban Institute report found that between 2019 and 2022, Black and Hispanic adults were consistently at greater risk of food insecurity than White adults, due to racial injustices and systemic inequalities. The shares of Black and Hispanic adults reporting food insecurity in 2022 were roughly 50 percent higher than the share of White adults reporting food insecurity, the report stated. In 2021, 29.0 percent of both Black adults and Hispanic adults were food insecure. In 2022, 30.4 percent of Black adults and 32.6 percent of Hispanic adults, or nearly one-third of both populations, were food insecure.

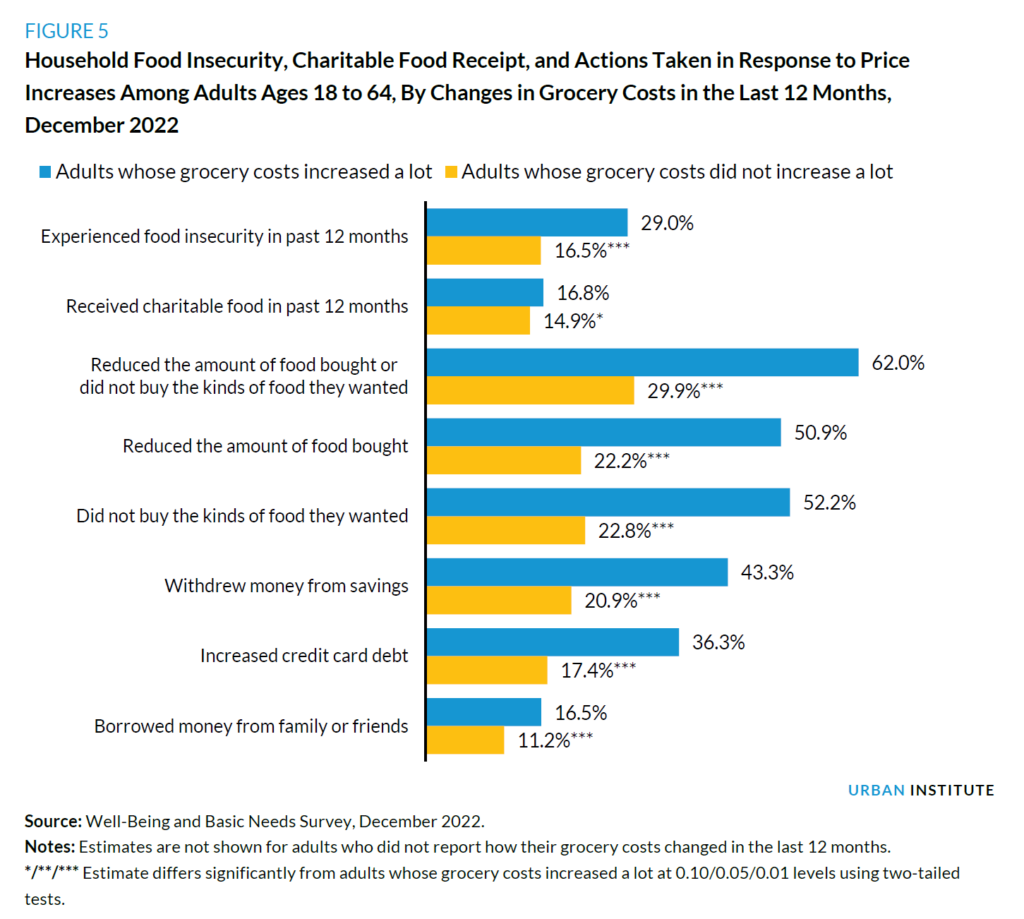

The problem of food insecurity has gotten so pervasive that White adults saw the largest increases, going from 15.6 percent in 2021 to 21.6 percent in 2022. Still, the report found Black and Hispanic adults who faced higher grocery costs were more likely than White adults to experience food insecurity, to increase credit card debt or borrow money from family and friends and to reduce the amount of food they bought.

Malik Yakini, executive director of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, noted to The Final Call that even in good times, Black people struggle.

“When we see these statistics that say that conditions are worse, it was kind of already worse for us. So, we’re just talking about degrees of injustice and to what degree are we negatively impacted,” he said. “We’re in a situation where we’re dependent upon other people and that we are subject to whatever conditions they might impose, and that includes manipulations of the prices of food.”

He explained corporations largely determine the tremendous increases in food prices.

“We’re seeing tremendous profits being made by the large, multinational corporations that produce, aggregate and sell food,” he observed. “And so we need to be trying to figure out how we break free from that and how we create a situation where Black people are governing ourselves and making decisions in our own best interest.”

Causes of food insecurity

The Urban Institute report states that inflation has also affected rent, home heating, childcare, health insurance and mortgage payments. These surges not only cause families to consume less food and lower quality food, but they also force families into uncertain housing circumstances with risk of being evicted, the report says.

Some of the causes of food insecurity include poverty, unemployment or low income, the lack of affordable housing, chronic health conditions or lack of access to healthcare and systemic racism and racial discrimination, according to the organization Feeding America.

“It used to be that it was people making $35,000 or less a year and what we call the working poor,” Ms. Omilami said. She noted that due to inflation, they are now also serving the middle class.

“We now have a middle class that can’t pay their bills. And then you mix that in with out-of-control property ownership,” she said.

“Some families went from getting $200 a month, which is nothing, down to $20 a month for food stamps, when they cut, not only the pandemic additional that they were getting, but some families got cut out all together. And we know this because we feed these hundreds of families on a weekly basis and we ask them questions about what happened to them. Why are you in the food line driving this Honda, this Mercedes, driving this luxury car, this Jeep, or whatever it is that we’re not used to seeing?”

Ms. Omilami also described already existing health problems in the Black community, such as high blood pressure and diabetes.

“It doesn’t bode well for us to be eating poorly and a lot of families not at all. And then we have an encroaching summer, where children, who normally would eat breakfast and lunch at school, are at home. And so it’s not just an issue of poverty. It’s an issue of disposable income just being less and less,” she said.

Mr. Yakini explained in order to address food insecurity, the root causes have to be addressed, and not just the symptoms of the problem.

“The problem is not that there’s insufficient food. The problem is that there is not the acknowledgment that access to high-quality, nutrient-dense food is a human right. And then secondly, it’s a question of the recognition of who is actually human and deserving of that right,” he said.

Black food sovereignty

Ms. Omilami said change has to come from the top down. She asked for churches and civic organizations to do more food drives for themselves and for organizations like Hosea Helps.

“If your congregation has numbers in it that are not eating, that are hungry, then you should be feeding them. If they don’t have clothes, you should be clothing them. You should be taking care of the widows and orphans in your church. And that’s what Christ said that true religion is, taking care of the widows and the orphans and feeding the sheep, not just spiritually, but physically, because it’s hard for a hungry man to hear the gospel,” she said.

“Just because a child is full doesn’t mean that they’re healthy, because they could be full on junk food. We need to stop our families from eating out,” she added. “We have to go back to the old school ways of cooking at home. Going to our kitchens, as busy as we are moms and dads, and figuring out, okay, how do I feed this family without spending $100 or more, a couple of hundred a week at these fast food places.”

She further stated that Black farmers need more support. “And that’s why I admire the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan so much, is because I know that he is aware of the need for farmers and for farming and for fresh food that we grow ourselves,” she said. “And how can we take his lead and create these community farms that might be able to feed families on a certain street or a certain senior high-rise?”

Kamal Bell, founder of Sankofa Farms, a 12-acre farm in Orange County, North Carolina, a little over 15 miles from Durham, got the idea for the farm after reading “Message to the Blackman in America” by the Honorable Elijah Muhammad while in college. Part of the goal, he said, is to give people who are affected by food deserts access to healthy and nutritious food.

He believes that in order to decrease food insecurity, more people have to be willing to work the farm. “We need distribution systems. We need drivers, trucks and systems where we can be able to work, not simply to push out food,” he said to The Final Call.

“We have to do it collectively. Farming has to be something that we pay attention to, and that has to be the focus of what we’re doing and not just mere conversation. There needs to be actual action behind us centering farming again,” he added.

For Malik Yakini, the rise in food insecurity “magnifies the need for us to practice Black food sovereignty and to grow our own food, number one, as much as we possibly can, to create the mechanisms for distributing that food, and to create the retail outlets for selling that food.”

Yakini, the executive director of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, explained the first step in creating much-needed infrastructure is changing the mindset from consumer to producer. He outlined the need for traditional, rural farms with large acreage and the ability to grow grains and raise animals, urban farms and backyard and container gardens.

“We’re growing it closer to where we have centers of population density. It’s better for the environment, but it’s also better for the health, because the larger the distances are that you transport food, the less nutrient-dense it becomes. And so if you’re able to pick a tomato and eat it within an hour, you’re getting more nutrients than if you were eating a tomato that was harvested three weeks ago and transported across the country before it ripened,” Mr. Yakini said.

The next step is making sure food is transported to ensure its safety and aggregating food from multiple sources.

“We have to have things in place at the farms, what we call ‘wash pack cool’ stations, so that food can be packaged correctly at the correct temperature so that we don’t have outbreaks of bacteria in the food. The food needs to be transported safely, which requires vehicles, and in some cases, requires refrigerated vehicles so that we can move the food again safely without fear of bacterial contamination,” he said.

“It involves having aggregators because most retail stores don’t want to have to go to 20 different farmers to get their crops. They want to go to one kind of main distributor who’s getting those crops from multiple farmers.”

“And then of course, we need markets in our community, grocery stores,” he added. “Our organization favors cooperatively owned stores rather than just the individual ownership model, so that the community itself can have ownership of these retail establishments from which we can purchase our food.”

Lastly, he added, “We need to be thinking about how we process that waste that we’re producing from the foods that we grow and the foods that we eat, and how we process that in a way that adds vitality to the earth and doesn’t contribute to methane gasses and global warming.”

He sees the work of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam as a template for what needs to be done.

“The Honorable Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam were way out in front of the rest of us in terms of this understanding, and not only just having that understanding, but actually creating the model, owning farms, owning trucks, owning airplanes, being able to import food internationally,” he said.