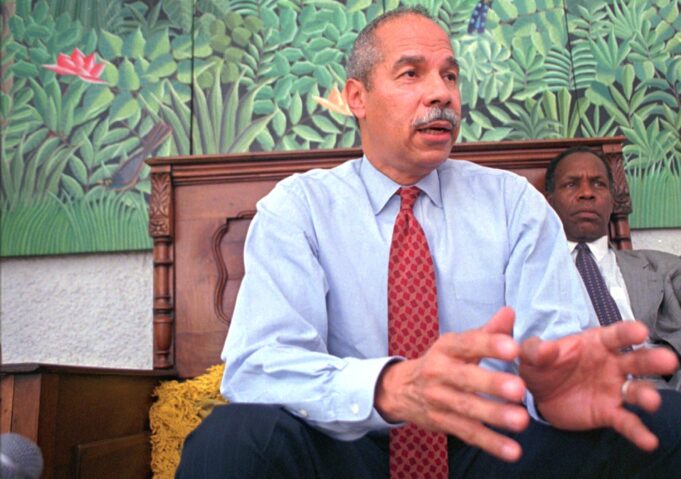

A mighty tree has fallen as the African proverb goes, with the passing away of Randall Robinson, the renowned human rights advocate, lawyer, author, and co-founder of TransAfrica Inc., an advocacy group for Africa and the Caribbean. He died March 24 in a hospital from aspiration pneumonia on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts and Nevis, where he and his wife, Hazel Ross-Robinson, resided for the last 22 years. He was 81 years old.

Mr. Robinson is remembered as a stalwart of Black internationalism, brilliance, and integrity as a major voice for justice over the last two centuries. In an official statement to The Final Call, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam reflected on his friend and brother.

“I was shocked and saddened to hear of the passing of my Brother and friend in the struggle for justice for our people,” said Minister Farrakhan.

“Brother Randall is one of the most erudite and scholarly Brothers on the struggle of Black people and our cry for justice,” reflected the Muslim leader. Mr. Robinson’s adopted home of St. Kitts-Nevis is the birthplace of Minister Farrakhan’s mother and a place the two leaders bonded as friends.

The Minister told The Final Call: “I shall always honor his memory” and that he “fell in love with him as a companion in struggle” and was “deeply impressed” by his integrity. Because of the depth of Mr. Robinson’s contribution, he will live beyond the power of death, he noted.

“He is among the few that are worthy of honor in this life and granted Paradise in the life to come,” said Minister Farrakhan.

When one thinks about fighting for freedom, justice, and equality, whether it is arguing the legitimacy of reparations to the descendants of enslaved Blacks in America or battling ruthless apartheid in South Africa or a callous U.S. policy in Haiti, the name Randall Robinson strikes a chord. He is being remembered as a stalwart of Black internationalism and a major voice for justice in the last century.

“You cannot write the history of modern-day South Africa nor Haiti, without including Randall,” said Dr. Ray Winbush, director of the Institute of Urban Studies at Morgan State University.

Dr. Winbush who was a friend and colleague credited Mr. Robinson with widely sensitizing public awareness and support around eradicating decades of brutal White minority rule and their system of apartheid in South Africa. Defeating apartheid in the 1990s ushered in the current African National Congress government and presidency of Nelson Mandela, the country’s first Black president.

“The fall of apartheid was in part due to Randall because he made the world aware of the horrific nature of apartheid during the 70s,” Dr. Winbush told The Final Call.

With his unwavering advocacy, there is no question he played a pivotal role in defeating apartheid. “But he did not stop there,” said Dr. Gerald Horne, professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston. “He was also an activist with regard to Haiti.”

Dr. Horne recalled the 27-day hunger strike Mr. Robinson embarked on to push the administration of Bill Clinton to reverse a policy of returning Haitians fleeing a bloody aftermath of a coup d’état against Haiti’s first democratically elected president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Mr. Robinson vowed to survive on juice and water until the U.S. changed course. Mr. Aristide was eventually restored to power, before being deposed again in a U.S.-France-supported coup in 2004. He was exiled to the Central Africa Republic, where he maintained the U.S. flew him against his will.

At the annoyance of Washington, Mr. Robinson personally intervened to return Mr. Aristide to the Western Hemisphere—first to Jamaica—and then granted political sanctuary in South Africa until returning to Haiti in 2011.

The moves reflected a long history of resisting injustice that began while attending Harvard Law School. He led Black students in taking over an administration building to protest Harvard’s investment in Gulf Oil—involved in supporting Portuguese colonialism in Angola. Black internationalism was central to him most of his adult life, said Bill Fletcher Jr., who succeeded Mr. Robinson at TransAfrica.

“There has been a long tradition of Black internationalists, and Randall fit well within them,” said Mr. Fletcher. They believe the resolution to the freedom struggle of African Americans cannot materialize absent a global fight for freedom. “Randall was part of that tradition,” said Mr. Fletcher.

Mr. Robinson’s effective pressure campaigns such as relentless weekly sit-ins at the South African embassy in Washington and organizational work around these issues made him a towering figure in stature and influence.

“He became de facto, sort of the Secretary of State of Black America when it came down to Caribbean and African issues,” said Dr. Ron Daniels, president of the Institute of the Black World 21st Century and founder of the Haiti Support Project. “He had that kind of stature.”

Dr. Daniels, who worked on the same transnational issues as well as on reparations, said Mr. Robinson’s contribution set a “powerful impetus” and gave the movement a “big boost,” especially through his books like, “The Debt.”

For Dr. Horne, his writings are one of the gifts he has left that will be educating future generations. As a profound thinker and prolific writer, Mr. Robinson penned several best-sellers including, “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” “The Reckoning: What Blacks Owe to Each Other,” “Defending the Spirit: A Black Life in America,” “Quitting America: The Departure of a Black Man from His Native Land,” and “An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President.” He also wrote two novels, “The Emancipation of Wakefield Clay,” and the much celebrated, “MAKEDA.”

Others lauded Mr. Robinson for his tenacity of spirit to drive change. “His voice, his eloquence, moral conviction and strategic leadership were legend,” tweeted Sherrilyn Ifill, former president, and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. He represented a “powerful example” of how to make a difference as a Black lawyer unrelentingly strategizing against systemic racism, she said.

Molded for a life of service

Randall Maurice Robinson was born on July 6, 1941, in segregated Richmond, Va., to educators Maxie and Doris Robinson. His three siblings included another history maker, the late journalist Max Robinson—the first Black co-anchor on a national news network, on “ABC World News Tonight,” who died in 1988.

His formative experiences living under southern White “domestic apartheid” molded his subsequent social justice journey. “When one gets on a bus and has to sit in the back—even a two-year-old child understands,” he told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1987. “Life is always a mixed blessing of pain and pleasure, but there was too much pain and no justification.”

Mr. Robinson attended Norfolk State University on a basketball scholarship before graduating from Virginia Union University in 1967. He later graduated from Harvard Law School. On a fellowship, the human rights advocate spent time in Tanzania, East Africa before returning and working for congressmen Rep. William Clay Sr. (D-Mo.) and Rep. Charles Diggs Jr. (D-Mich.), founding members of the Congressional Black Caucus. He went on to co-found TransAfrica Forum in 1977, and later the Free South Africa Movement.

Mr. Robinson stepped down from TransAfrica in 2001 and repatriated to St. Kitts-Nevis—where his wife hails from—for reasons he documented in “Quitting America: The Departure of a Black Man from his Native Land.”

He wrote about his weary disillusionment with a super-power wreaking havoc on weaker nations and its unanswered accountability for the damaged souls of Black folks languishing within America. In a kindred spirit of people like Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Dubois and writer James Baldwin who also found solace elsewhere, he described America as, “the country that was always and never my home.”

In a 2005 interview, Mr. Robinson spoke of being exhausted with an abusive America that for Black people is far different from a self-purported image as the land of the free and bastion of democracy.

“Black people in America have to, for their own protection, develop a defense mechanism, and I just grew terribly tired of it,” said Mr. Robinson. “When you sustain that kind of affront, and sustain it and sustain it and sustain it, something happens to you,” he added.

Dr. Winbush summed up Randall Robinson as a man of integrity dedicated to Black folk everywhere like a “jegna” (hero, warrior) who knew his community and was willing to defend it and die for it.

“A jegna is like Dr. King … Marcus Garvey … Minister Farrakhan,” said Dr. Winbush. “We don’t have that many jegnas left.”

Besides his wife of 35 years, Hazel Ross-Robinson of St. Kitts, he leaves two children from a previous marriage: Anike Robinson of Silver Spring, Md., and Jabari Robinson of Philadelphia; a daughter from his second marriage, Khalea Ross Robinson of Manhattan; two sisters; and three grandchildren. A media release stated a funeral service is slated for April in St. Kitts followed by a memorial service in Washington, D.C., in May.