There appears to be geopolitical house cleaning in Africa after a wave of foreign nationals were expelled from the West African nation of Burkina Faso within a span of several weeks. Observers and Africa watchers said there is a surge of anti-French and anti-West sentiment among the Burkinabe people and government.

Some observers say the tension highlights the disillusionment of African nations toward France, a neocolonial power, and the United States adversely involved in their affairs. Dissatisfaction is strong over the lackluster results in a feverish struggle against violent extremists terrorizing the Sahel and West African regions.

“The French position is, you need our protection,” said Abdul Akbar Muhammad, the International Representative of the Nation of Islam and the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan. “We can step in to protect you, but you have to see things our way,” said Mr. Muhammad.

He was describing a condescending, paternalistic attitude of France toward its former colonies that it has provided military help. However, extremism has intensified, and Africans are openly rejecting France.

He said nations like Burkina Faso and Mali are exhibiting legitimate backlash against foreign domination and historical French and Western meddling.

Cleaning out the house

On Jan. 3, heads turned when Burkina Faso, a former French colony, told the ambassador of France: “À bientôt” (“see ya later”), and declared him persona non grata. Burkinabe spokesman Jean-Emmanuel Ouedraogo confirmed to media outlets that Ambassador Luc Hallade was told to leave, however, gave no further details.

Meanwhile, the French Foreign Ministry said Burkina Faso sent a letter in December 2022 requesting France replace the diplomat, which was rebuffed as coming outside of protocol, and defended Mr. Hallade. French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna told French LCI TV on Jan. 5 that she supports the ambassador and that the embassy staff is doing a remarkable job in “difficult” conditions.

Relations between the countries soured after prolonged insecurity triggered by armed extremist groups led to political instability and military coups in January and September 2022.

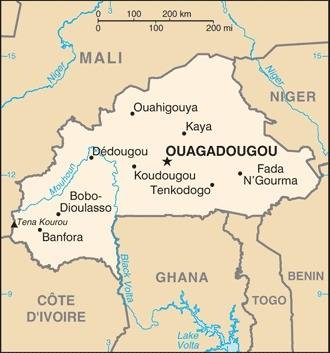

In the second coup, the Burkinabe people targeted the French embassy, cultural center, and military base in the capital Ouagadougou. The cry was for France and its special forces to leave, and for Russia to come to help fight the insurgents. The coup was the latest in the troubled Sahel region inundated with growing extremism.

The ambassador controversy came weeks after the ruling Patriotic Movement for Safeguarding and Restoration (MPSR) suspended all broadcasts by Radio France International (RFI) for broadcasting an “intimidation message” attributed to a “terrorist,” said an RFI news release on Dec. 4.

In late December the government expelled the United Nations resident coordinator for Burkina Faso, Barbara Manzi, an Italian diplomat.

Burkina Faso’s Foreign Minister Olivia Rouamba said Ms. Manzi’s decision to “unilaterally” withdraw non-essential UN staff from Ouagadougou was the primary reason for her expulsion.

“Ms. Barbara Manzi, resident coordinator of the United Nations system, is declared persona non grata on the territory of Burkina Faso. She is therefore requested to leave Burkina Faso today, December 23, 2022,” the statement said.

The ministry accused her of painting a negative picture of the security situation, which it said undermines the country. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres rejected the persona non grata status as illegitimate. He cited the UN charter stating that only the UN Secretary-General, as the Chief Administrative Officer of the global body, holds the authority to withdraw any United Nations officials.

Not feeling France or the West

The sentiment and tension between former colonial power France and Burkina Faso has been spiking since the new junta leader, Captain Ibrahim Traoré, 34, took power in September from Paul-Henri Damiba, another strong man, who seized power by the gun in January 2022.

Mr. Traoré officially assumed the functions of the president on Dec. 22 and has been more open to working with other countries, notably Russia.

Russia’s foreign ministry said Burkinabe Prime Minister Apollinaire Joachim Kyelem de Tambela visited Moscow in December to bolster relations and discuss efforts to combat extremists in the region.

The groups reportedly linked to ISIS and al-Qaeda made Burkina Faso an epicenter of combat in the Sahel region. The crisis there and in neighboring Mali resulted in an acute humanitarian disaster. Thousands succumbed and nearly two million people in Burkina Faso were displaced by the ongoing conflict.

Overall, France has been in the mix militarily since 2013. But after 5,100 soldiers and a whopping $1.2 billion per year for nine years, the French engagement is seen as a colossal failure. Last year, French forces withdrew from Mali after relations with Mali’s junta unraveled. The fallout opened the door for alternative forces like the Wagner Group, a private Russian military contractor.

Observers told The Final Call that America cannot be overlooked in the conversation about failed anti-terrorism efforts in Africa. Both the United States and France used extremism as pretext for their military presence on the continent. In Africa, the association between Washington and Paris are like “two peas in a pod.”

“You can’t reject France and not eventually get around to reject the United States presence,” said Netfa Freeman, an organizer with the Pan-African Community Action. “They go hand-in-hand,” he said. Mr. Freeman explained the powers are part of a U.S.-EU-NATO axis of domination and a Pan-European capitalist, patriarchal project.

Others noted some of the junta leaders rejecting Western powers once had relations with them. Strongmen who took power in countries like Mali and Guinea-Conakry had close ties to the U. S. Africa Command (AFRICOM). They attended training programs and war colleges in America.

“However, their frustration with France and the United States is reaching a boiling point at this stage,” said Abayomi Azikiwe, commentator and editor of Pan Africa Newswire.

Mr. Azikiwe reasoned the rationale behind AFRICOM—at least the way it was sold to Africa—was only as a support through training programs, logistical assistance to enhance the security capacity of countries, and help anti-terrorism campaigns.

“Yet the terrorism has gotten worse over the last decade and a half since AFRICOM has been in existence. Same is true for the French Operation Barkhane which has been dissolved,” said Mr. Azikiwe.

“So, I think it’s a frustration on the part of these governments,” he added.

Roots of the mayhem

Analysts say Africa’s Sahel region has been plagued with armed insurgencies since 2013. However, the roots of havoc extend further with the U.S.-NATO-induced overthrow and assassination of Libyan leader Muammar Gadhafi in 2011.

At the time, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam forewarned the serious consequence of their actions would be mayhem, devastation, and conflict in Africa, which is now being witnessed.

“Your joy will be short-lived for what you have done America, England, France, Italy, Canada,” warned Minister Farrakhan in a WVON radio interview in October 2011. “What just happened has let the dogs of destruction out,” Minister Farrakhan said, warning of a future which is now the current reality in Africa.

Bloodshed gripping the desert Sahel of northern and western Africa and other parts could be examined in the context of the geo-strategic importance of Africa for Western nations and the struggle to remain relevant powers in this century.

The demise of Col. Gadhafi, the reigniting of historical struggles between Berber ethnic groups and several governments across Africa, coupled with arms and training must also be considered.

Then there are economic challenges and dissatisfaction threatening social implosion in Europe and America while Africa is seen by Western imperialists as the last frontier for their survival. Superpower status depends on control of Africa’s strategic resources as the Western world declines.

The root cause also points the finger at Washington’s past penchant for supporting terrorist groups in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and Libya as opposition forces to undermine America’s geopolitical foes.

Mr. Azikiwe said the 2011 “counter-revolution” in Libya weighs heavy on the instability throughout North and West Africa. The current problems are aftershocks, he explained.

“We’re seeing, now almost 12 years later the bitter fruit from that military intervention, under the then-President Barack Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton,” stated Mr. Azikiwe.

The destruction of Libya was AFRICOM’s first full-scale project. “People are tired of them,” he said. “People have seen the impact of their work.”