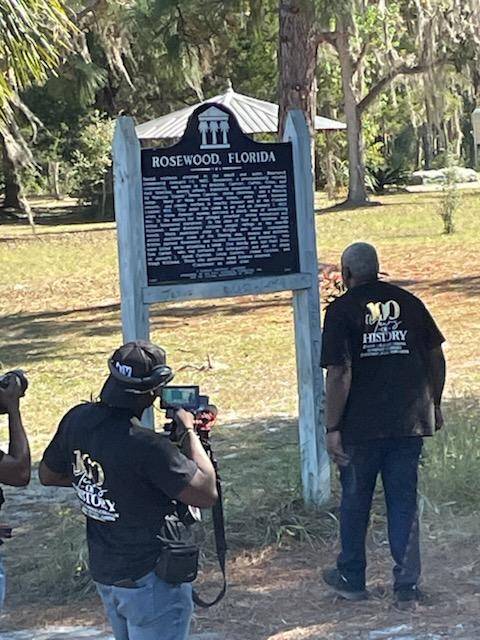

In 1922, Rosewood, Florida was a thriving, majority-Black town of about 200 people with only one documented White family. In the words of Raghan Pickett, a descendant of the Rosewood massacre, “There were schools in Rosewood, a Masonic lodge in Rosewood. They even had their own baseball league in Rosewood.”

Fast forward to 2023 and “as far as African Americans in the Rosewood area, none. None at all,” said Gregory Doctor, another descendant of the Rosewood massacre, to The Final Call.

January 1, 1923, the thriving community turned into a place of terror and fear after Fannie Taylor, a 22-year-old White woman, claimed she had been assaulted by a Black man. Her words “opened the doors for the lynch mob to come in. And over a seven-day period of time, they went on a killing spree,” Mr. Doctor explained.

From January 1 to January 7, 1923, White lynch mobs, including the Ku Klux Klan, raided Rosewood, killing residents and burning homes and property. “The mob brutally tortured and lynched Sam Carter, and also tried to lynch Aaron Carrier, who was dragged behind a car and left for dead.

No one was immune to their rage. With a houseful of terrified children huddling inside, prominent Rosewood resident Sarah Carrier was gunned down on her doorstep, and when her son Sylvester fought back, killing two white men, he was murdered as well,” says the website rememberingrosewood.com.

“Residents fleeing the violence were forced to seek refuge in nearby woods and swamps, while mobs hunted them and razed Rosewood to the ground,” the website noted.

Official reports state that eight people died, six Black and two White, but some historians put the figure as high as 200. After the massacre, the state called on a grand jury, but no one was held responsible.

“No one was ever punished for what happened that week,” said Dr. Maxine D. Jones, a history professor at Florida State University, to The Final Call. “No one was ever prosecuted for the theft that took place that week or for the burning of the town and the stealing of possessions,” she added.

“100 years later, Black people still don’t have their land, [and] 100 years later, Black people still aren’t welcome on that property,” Ms. Pickett said, stating that the prejudice is still present.

Reflecting on history

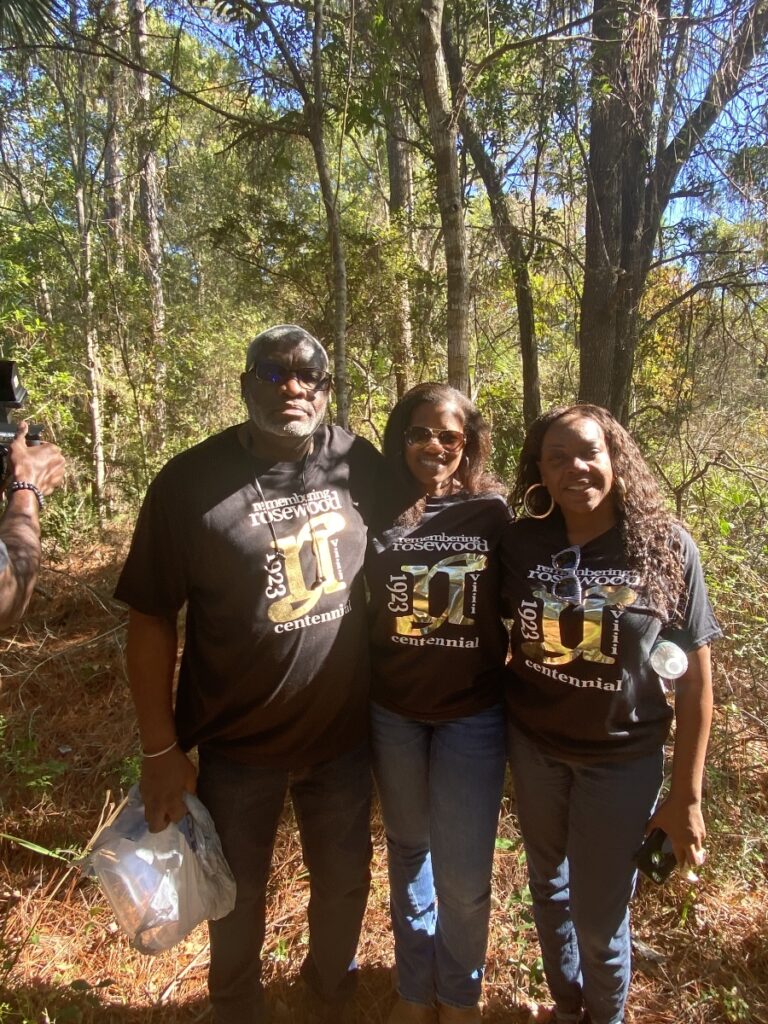

The descendants of Rosewood are holding a week of events to commemorate what happened to their ancestors 100 years ago. Starting Sunday, Jan. 8, a wreath-laying ceremony will take place with a keynote presented by Gainesville City Commissioner Dr. Cynthia Chestnut.

“My family didn’t have a proper burial,” Mr. Doctor said. The night that the massacre took place, they were ran out of their town. Many family members and my mom and some of the ones that I’ve had an opportunity to have a conversation with, they were not afforded to put on any clothes, any shoes. They said [it was] about 13 or 14 degrees. It was really cold, extremely cold that night.”

He referenced Marvin Dunn, a retired chairman of the Department of Psychology at Florida International University, as the only Black man who owns property in Rosewood today. The wreath-laying ceremony will take place on his five acres.

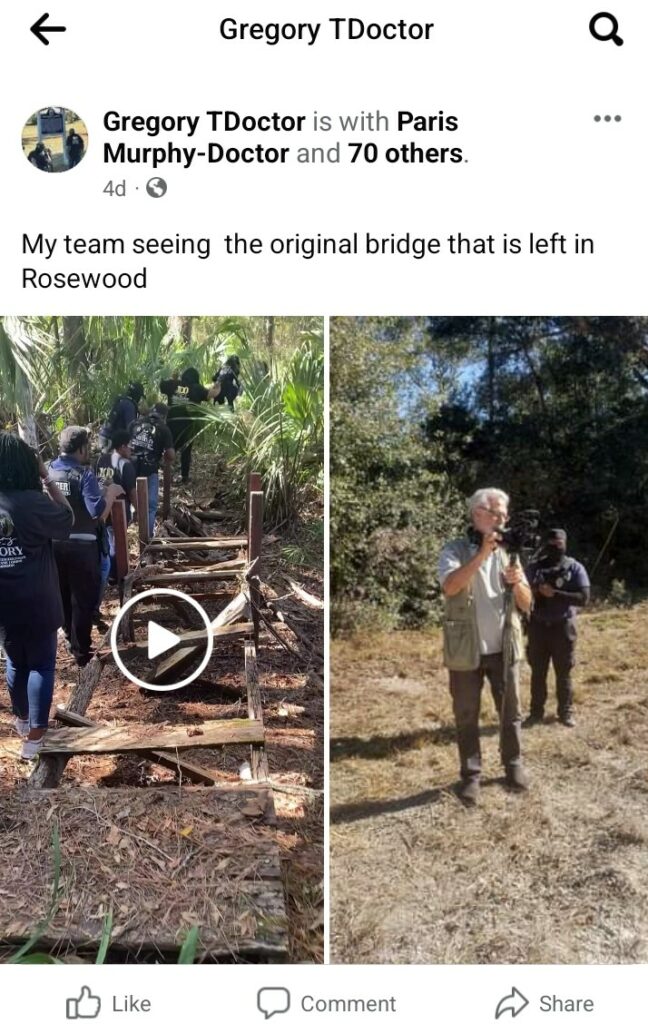

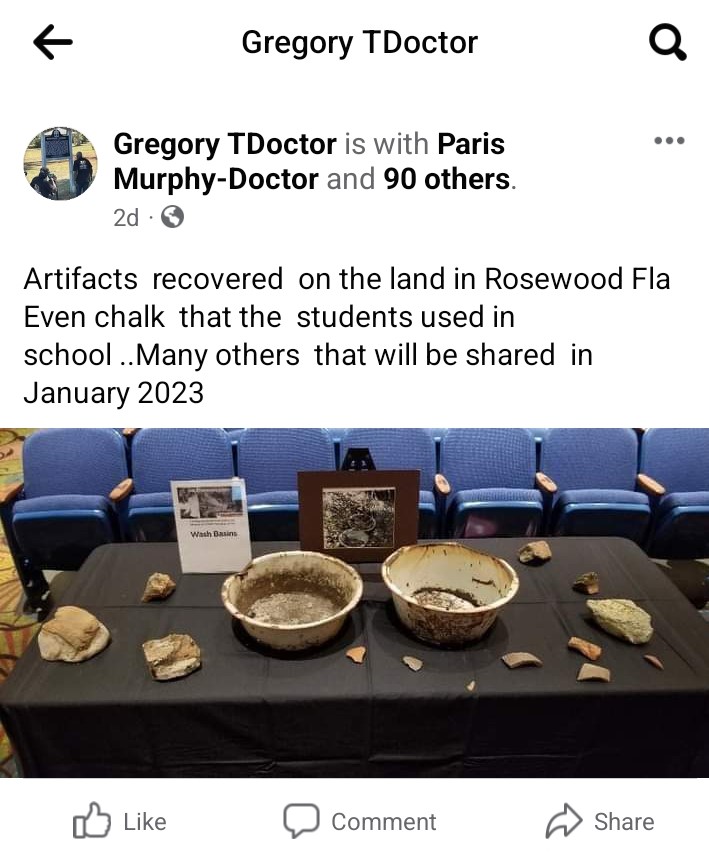

The events will be hosted by the University of Florida. A Rosewood traveling museum will be open from Jan. 9 to Jan. 14 inside of the university’s Levin College of Law library, “along with a lot of the artifacts that Dr. Dunn has recovered on the property,” Mr. Doctor said.

“He’s recovered the Masonic sword and even the chalk that the students used when they were in school at the Masonic lodge in Rosewood, and some of the pots and dishes and so forth.”

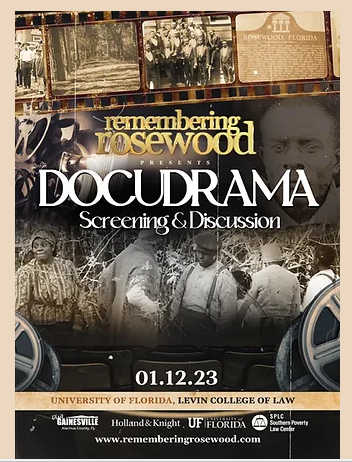

A Rosewood docudrama screening and discussion will occur on Jan. 12. Three panel and forum discussions will take place on Jan. 13: a dialogue on Rosewood’s place in American history, a conversation on American history, race relations, equality and generational wealth, with guest speaker civil rights attorney Ben Crump, and a conversation with the next generation, including two descendants of Rosewood: Raghan Pickett and Brian Jamal Scantling.

Those attending the commemoration will have the opportunity to view “Rosewood,” the 1997 historical drama directed by John Singleton, based on the true story of Rosewood, on Jan. 14. The week of events will close with a “Redefining the Next 100 Years” black-tie awards gala with guest speaker Rev. Dr. Jamal H. Bryant.

Mr. Doctor was inspired to get involved with planning the 100-year commemoration of the Rosewood massacre by his sister, Barbara Scantling Moore, who was the historian of The Rosewood Family, Inc.

The secret

“Rosewood was a secret,” Mr. Doctor said. He was 19 years old when he came into the knowledge of Rosewood, as its story was only shared amongst the elders of his family. Though currently the owner of a luxury travel transportation service in Atlanta, Mr. Doctor is originally from Florida. His family came from a small town called Lacoochee, Florida, which is a little over 90 miles away from Rosewood. But he learned that some of the perpetrators of the Rosewood massacre had also moved there.

“I can recall as a child during the Christmas holidays, like this time of the year leading up into New Year. Those family members that had knowledge about Rosewood—the kids at that time, we couldn’t be sitting in the house among the elders. We had to go outside and play. But during that time period, they would get among themselves, and they’d be very depressed, extremely depressed, and I had no idea why,” he expressed. “You imagine for 70 years carrying this inside you and not being able to share the story with the world.”

The story of Rosewood wasn’t brought to the attention of the American public until 1982 when an article written by an investigative journalist was published.

Mr. Doctor and Ms. Pickett noted that the massacre in Rosewood divided many families, particularly between 1923 and 1982. “A lot of people went in different directions. They changed their names, they changed their date of birth, they lost contact. So, some of the family members would not reconnect until they started seeing the news media in 1982,” Mr. Doctor said. “That was traumatic within itself right there. Because I would always ask my grandmother, I would say, ‘Why is our family so small?’ And she said, ‘I don’t want to talk about that.’”

He proposed professional counseling for the families, as a way for descendants to overcome the lasting effects of Rosewood and to have open discussions around it.

By the time Ms. Pickett, a third-year political science major at Florida A&M University, was born in 2002, the story of Rosewood had been in the public arena for 20 years. For her, Rosewood was never a secret. Still, she said that her older family members would not speak of the Rosewood massacre.

“Now when we hear the story, we’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, they had to have been experiencing some type of sadness or trauma or something like that,’” she said. “But as far as our families, they never identified it and pinpointed their feelings as being traumatic. They kind of moved to a new place and just started brand new lives. They were resilient. You know what I mean? They worked hard.”

Ms. Pickett, along with her mom, aunts and brother, is a recipient of the scholarship born from the 1994 House Bill 591, which provided $2.1 million in compensation to Rosewood descendants. Her great aunt initiated “bringing the family back together” by putting on an annual “Rosewood family reunion,” a tradition continued today and is usually attended by a minimum of 100 people.

“Ever since I was young, I would always attend the family reunions, so I’ve always been informed of my family’s history, the descendants,” she expressed. “I’ve also had the opportunity to meet one of the descendants, my uncle Willie Evans. So, I’ve always been raised in the aura of Rosewood, and I think that kind of shaped my political interest in wanting to pursue a career in law, because I love history and law and civil rights.”

Dr. Ray Winbush, a research professor and director of the Institute for Urban Research at Morgan State University, described what happened in Rosewood as “a massive cover-up.”

“Everybody knew Tulsa had happened,” he said, referring to the 1921 Tulsa race riot or the Black Wall Street massacre where again, mobs of angry Whites killed Black residents and destroyed and burned property.

“The governor and government of Florida tried to act as if nothing had occurred about Rosewood. It wasn’t mentioned in history books at all. It made a little bit of press, mostly locally but not nationally,” Dr. Winbush said to The Final Call.

Dr. Jones played a key role in writing the historical report used by the Florida legislature to grant descendants compensation. In her mind, “It’s almost like [the survivors] took a vow of silence because they didn’t know how Whites would respond.”

“I’m sure those people who survived Rosewood never completely trusted White Americans anymore. So, I think that’s why it was kept buried for so long,” she said. “And Rosewood isn’t the only one that’s been buried. There are other incidents like that, but we don’t like to talk about these things because … it puts the state and the country in a bad light. But this is our history, and we need to embrace the good and the bad.”

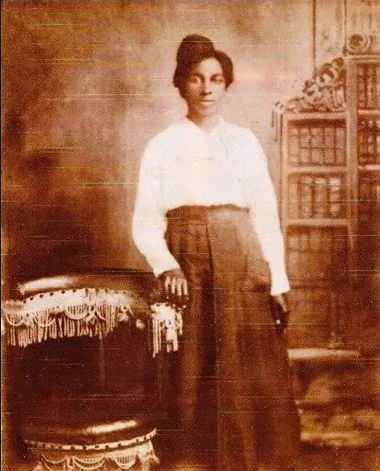

The last survivor of the Rosewood massacre, Mary Hall Daniels, died at the age of 98 on May 2, 2018. She was only three years old when the White mob destroyed her home, forcing her family to escape. In 2009, she received the Rosa Parks Quiet Courage Award for educating others about the Rosewood massacre.

The legacy

The Rosewood descendants and professors of history expressed the importance of Black people knowing what happened in Rosewood.

Dr. Jones stated that understanding the past gives understanding to the present. “I think it also provides a roadmap for the future. I mean, how can you examine race relations in the present without knowing what happened in the past?” she questioned. And I think there are threads that connect the present and the past. And I think there are a lot of answers that our history can provide us for the way things are now.”

In particular, she pointed out the current relationship between the Black community and law enforcement when it comes to the killing of Black men. “There are probably some threads that can be traced back, not just to Rosewood but all of these incidents of racial violence where no one was ever held accountable,” she said.

“It’s important for us not to forget, it’s important for us to remember and it’s important for us, especially the Black community, to continue to not live in the past, but to remember where we came from and the sacrifices and the loss of lives that have enabled us to get to where we are today,” she added.

Mr. Doctor visited Rosewood two months ago. “There are some trailers there,” he said. “The only home that existed from 1923 was Mr. (John) Wright’s house, the house they used to protect some of the women and the kids … until the train came and got them to safety.”

John Wright was a White store owner. According to a 2021 article by the Tampa Bay Times, Lizzie Jenkins of the Real Rosewood Foundation is interested in turning his house into a museum. The house was donated to the foundation in late 2021.

Mr. Doctor argues that the governor and the state of Florida are keeping the history of Rosewood from being taught in public schools, despite the 1994 bill requiring the history to be a part of the school curriculum. He stated that though 350 descendants of the Rosewood massacre have now successfully graduated college under scholarship money given through the reparations bill, “it wasn’t an easy journey to get to that point.”

“They want Rosewood to go away. They don’t want to talk about it. They don’t want the conversation to come about. They want it to go away. They don’t want people to come out to do tours,” Mr. Doctor expressed.

For Dr. Winbush, the story of Rosewood is a story of resistance. If we don’t understand how we resisted, we won’t know how to act, he stated. He expressed that Black people today must learn from history in order to be prepared to defend their communities from future attacks.

The professor is a longtime advocate for reparations for Black people. He believes the potential of Rosewood should have been taken into account in the compensation received.

“I think that White people always try to cover up their destructive behavior in terms of compensation by offering us insulting amounts of money,” he said. “What if Rosewood would have never been burned down to the ground? That could’ve been one of the largest cities in Florida right now. We don’t know. The same with Tulsa.”

For Mr. Doctor, “The future starts with honoring the lives that were taken, acknowledging the trauma that was left behind, sharing stories of the past and celebrating the promise of all that lies ahead.”

Ms. Pickett said that moving into the future, she sees that the descendants of Rosewood are more educated about what happened. “We’re getting more exposure, more media coverage and stuff such as that. So that is very helpful for future generations to come, so that younger people can look at this, younger descendants can look at this event and be inspired and informed and acknowledged,” she said.

“I think there will be more involvement coming from our family members. I’m obviously a descendant, so I’m going to try to do my best to continue the legacy and continue to spread the word.”

For more information about the 100-year commemoration of the Rosewood massacre, visit www.rememberingrosewood.com.