The latest iteration of “scramble for Africa” by foreign interests, is not only being seen in the number of countries involved, but with the U.S. military strategies utilized. The United States African Command (U.S. Africom) is pushing military might as seen in the August return of its annual Senior Enlisted Leader conference in which NATO participated. According to several media outlets, the conference marked a return of “face-to-face engagements after COVID-19.”

U.S. Africom defines its African military build-up, as a “shared understanding between Africom and our partners on the continent and serve to strengthen the relationships we have already built which are extremely important to our shared successes and increasing security,” said U.S. Marine Corps Sgt. Maj. Richard Thresher. He serves as command senior enlisted leader for U.S. Africa Command.

But what is never shared is that the U.S. military scramble in Africa, from its 2008 Africom beginnings through today, has increased over 2,000 percent. The U.S. military’s presence marked by it and France in the 2011 destabilizing of Libya and subsequent assassination of its leader, Muammar Gadhafi, also marked “the destabilizing of the entire Sahel region, (including) Chad, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso,” noted Maurice Carney, co-founder and executive director of Friends of the Congo.

Western military presence has historically been defined as protecting “strategic interest,” when in fact it is the history of European and U.S. access to Africa’s mineral and natural resources.

In the spring, U.S. Africom Gen. Stephen Townsend, among other things, revealed America’s real global power objectives.

He told the House Committee on Appropriations about the importance in the ability to access Africa’s rare earth metals used for mobile phones, hybrid vehicles and missile guidance systems. He stressed, “the winners and losers of the 21st century global economy may be determined by whether these resources are available in an open and transparent marketplace or are inaccessible due to predatory practices of competitors.”

U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, blowing Africom’s horn, recently explained, “Every day, Africom works alongside our friends as full partners—to strengthen bonds, to tackle common threats, and to advance a shared vision of an Africa whose people are safe and prosperous.” He made the statement at a ceremony honoring the new Africom commander, Gen. Michael Langley.

According to theintercept.com, that same day of Sec. Austin’s comments, the Defense Department’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies—a Pentagon research institution—issued a devastating report that directly refuted Austin’s positive assessments. “Militant (so-called) Islamist group violence in Africa has risen inexorably over the past decade, expanding by 300 percent during this time,” reported theintercept.com. “Violent events linked to militant Islamist groups have doubled since 2019.”

The history of the increase of U.S. military strikes over a 15-year period has America conducting no fewer than 260 airstrikes and ground raids in Somalia. This was done under the auspices of the secretive 127e authority, reported the Intercept, which allows U.S. Special Operations forces to train, arm, and direct local surrogates to carry out missions on behalf of America. The U.S. has also employed nearly a half dozen proxy forces in Somalia, the website reported.

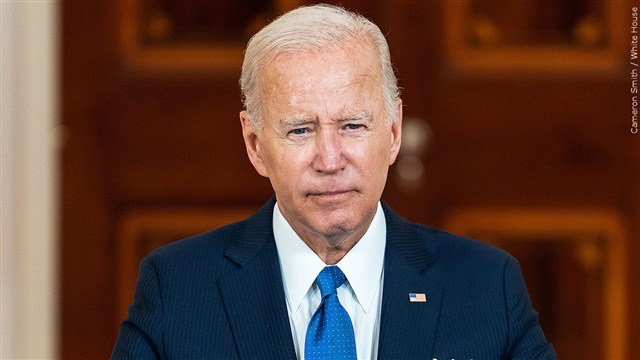

President Joe Biden’s “end of the forever wars” double-speak, has morphed into protecting U.S. strategic interest. According to Sarah Harrison, a senior analyst at the International Crisis Group and former associate general counsel at the Defense Department’s Office of General Counsel, International Affairs, despite Biden’s end of wars language, “Somalia remains one of the most active areas in the world for U.S. counterterrorism operations.”

“With Vice-President Biden’s election win, there is a real opportunity to re-imagine U.S. policy toward Africa,” Judd Devermont, a former CIA official and intelligence officer for Africa, said in 2020. Now the former CIA operative is the White House’s top Africa adviser, under the National Security Council, and there are fears that the U.S. is continuing its old approach with over-emphasizes on security policies that doesn’t meet the political moment in Somalia, Africa, or the Middle East, reported Vox.

The U.S. military is, among other things, one of the world’s foremost advisors on counterterrorism, and the Pentagon keeps more than 700 personnel in Niger and thousands in Djibouti. The U.S. deploys drone strikes and special operations forces against targets across the Middle East and Africa without much accountability or oversight.

The U.S. might be a long way from 1993 Black Hawk Down, the Somali battle or debacle that changed U.S. policy in Africa, but its footprint is still there. Follow @JehronMuhammad on Twitter