Police reform, an issue that helped catapult Joe Biden into the presidency, has been reduced to salt without savor as Black people continue to suffer under oppressive policing policies.

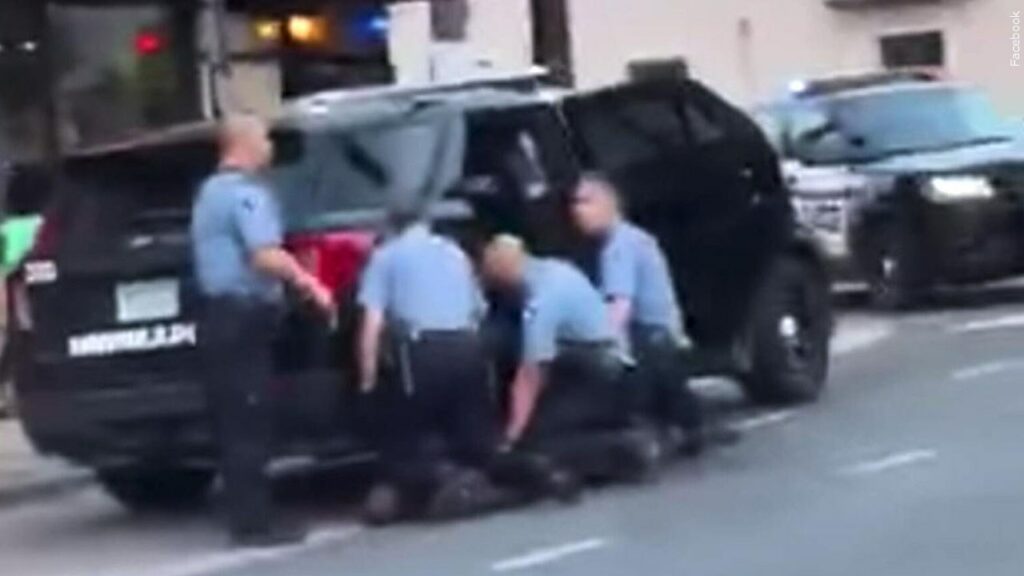

There is no doubt that the deaths of Jayland Walker in Akron, Ohio, George Floyd in Minneapolis, Breonna Taylor in Louisville and years ago, young Tamir Rice in Cleveland, and others at the hands of the police are etched into Black hearts and minds.

As these memories and problems fester and grow, people like Richard Randy Cox, 36, emerge and then go under the radar. He is among the nearly 400,000 people treated for violent interactions with police and security guards resulting in emergency room visits, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention compiled since 2015.

There is almost no reliable nationwide data on the full nature or circumstances of all such injuries. Approximately 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States do not tally or publish the number of people needing medical care after being struck by a Taser, breaking their arms, or rattling around in a van.

Mr. Cox’s story is particularly chilling.

As the 36-year-old was on his way to jail in the back of a police van in New Haven, Conn., last month, news reached his family. They discovered Mr. Cox had fallen and needed emergency spinal surgery. Viewing a police video revealed what happened during the previous hours.

Following a sudden stop, Mr. Cox was slammed headfirst into the back of the police van, causing him to go limp. He was left paralyzed from the chest down because he had no seatbelts to restrain him. He is believed to be another victim of an infamous police “rough ride,” where often handcuffed or unsecured prisoners are jerked, tossed and slammed inside these police vehicles through speeding and sudden, violent, deliberate stops.

Freddie Gray’s death was a turning point in many learning about rough rides and police brutality. The then 25-year-old Baltimorean died after being forced to ride unrestrained in the back of a police transport van in 2015. His injuries, which included a severed spine, were so severe that they led to his death days later.

Six police officers were charged in connection with the death, but none were convicted.

Now, seven years later, another young Black man is fighting for his life after suffering a severe spinal injury at the hands of police and shining a light on the enormous number of people hospitalized by the police.

Like Mr. Gray, Mr. Cox is left paralyzed from the neck down and is currently on a ventilator in an intensive care unit. His family and lawyers say police mocked him for being unable to sit up after he was injured and that his injuries are consistent with police torture.

“Help,” Mr. Cox called out multiple times.

After arriving at a detention center about eight minutes later, officers dragged Mr. Cox out of the van, placed him in a wheelchair, ridiculed him about his posture, and dragged him into a holding cell, said his family and lawyers. Police officials told reporters a day after the June 19 incident that Mr. Cox was at the detention center for “10 to 15 minutes” before paramedics arrived to take him to the hospital.

The five officers involved in the incident have been placed on paid administrative leave while the Connecticut State Police is investigating.

Rough rides have resulted in severe injuries, including spinal cord damage and brain injury, and even death. The victims of rough rides are often Black men who are already under duress when placed in the back of police wagons.

An executive order signed by then President Trump directed the Department of Justice to establish a national database to track excessive force by law enforcement officers. According to news reports, that effort stalled during Mr. Trump’s tenure and is on hold under President Biden.

A jury in 2019 did find a former St. Louis police officer guilty of giving two handcuffed prisoners a “rough ride” during a trip to a city police station. After a two-day trial, the jury found Lori Wozniak, 48, guilty of two misdemeanor counts of assault.

New Haven is currently spinning its narrative and circling its wagons. Officers in New Haven City are not required to restrain arrested individuals in the back of police transport vans. Still, they must immediately call an ambulance if a passenger becomes physically ill or injured.

Mayor Justin Elicker recently sent an email to city residents describing how the van abruptly stopped after a police officer braked to avoid an accident.

Although the officers did not appear to have injured Mr. Cox maliciously, Mayor Elicker said, their behavior “showed a callousness that is deeply concerning.”

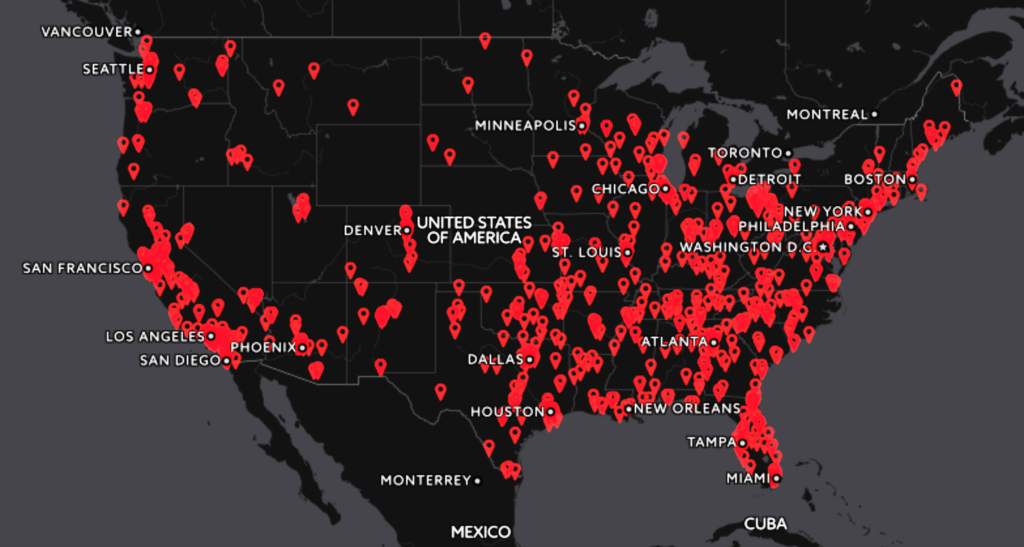

“In examining police violence outcomes of police killings, we found that Blacks were approximately three times more likely to be killed than Whites. Additionally, it is worth noting that 97 percent of the killings in our database occurred while a police officer was acting in a law enforcement capacity. This dataset does not include killings by vigilantes or security guards who are not off-duty police officers,” reported Mapping Police Violence.org.

Along with age and economic status, it is unknown what percentage of Blacks are hospitalized or crippled after police encounters. What we do know, according to a study published in the University of Chicago Press Journal titled “Police Use of Force by Ethnicity, Sex, Socioeconomic Class” is “results from prior studies using a nationally representative sample of U.S. residents ages 16 and older show that Black U.S. residents are 3–4 times more likely than White residents to experience police contact involving the use of less-than-lethal types of force and three times more likely to perceive the force used by police as excessive.”

“Similarly, findings from New York City’s stop-and-frisk data show that Black residents are 17 percent more likely to experience police use of hands, 18 percent more likely to be pushed into walls or to the ground, 16 percent more likely to be handcuffed, 24 percent more likely to have a weapon pointed at them, and 25 percent more likely to be pepper-sprayed or hit by a baton than White residents, even after accounting for gender, age, the reason for the stop, and whether the stop took place in a high-crime area or during a high-crime time. So it can be deduced the percentage of Black people among the 400,000 injuries is significant.”

Pamela Muhammad, a defense attorney from Houston, Texas, told The Final Call that at the end of the day, the only answer for Black people is separation. “I mean, aside from your dysfunctional police reforms, civilian review board, your lawsuits, this is what we have,” she said.

“The frequency of these police incidents is increasing; things are becoming more callous, whether it’s just angry racism or intentional harm,” Attorney Muhammad pointed out. “It’s just callousness and indifference that is negligent at best and intentional torture at worst.”