PHILADELPHIA—Born at Chestnut Hill Hospital in Philadelphia, where in the late 1980s there was no Sickle Cell Disease testing for infants, Tahiirah Austin-Muhammad went for six years without being diagnosed as carrying the disease. Primarily affecting African Americans, Ms. Muhammad was initially diagnosed as suffering from Leukemia before a Black hematologist, Dr. Kim Smith, intervened and correctly diagnosed Ms. Muhammad as suffering from Sickle Cell Disease.

Now one of three co-founders of Crescent Foundation SCD (Sickle Cell Disease), Ms. Muhammad—who has an undergraduate degree in biology from Neumann University and a graduate degree in public health from Arcadia University—began her arduous journey in life periodically suffering the debilitating conditions brought on by triggers like dehydration, stress, the common cold, etc., that could exacerbate her Sickle Cell Disease.

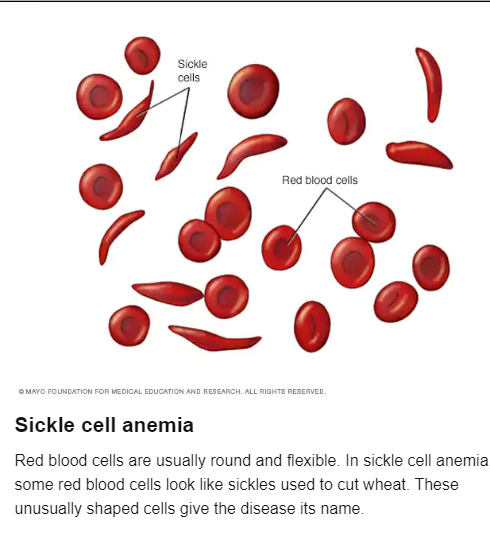

Sickle Cell Disease, according to the Crescent Foundation website, is the most commonly inherited blood condition. “It affects red blood cells, which are responsible for carrying oxygen throughout the body via a protein called hemoglobin,” the website explains.

“In people with Sickle Cell Disease, a hemoglobin mutation causes red blood cells to lose oxygen. When red blood cells become deoxygenated, they become rigid, and sickle shaped. This causes them to clump together, instead of flowing freely through small blood vessels. This can cause pain crises when oxygen doesn’t reach bone or muscles, or acute chest syndrome and stroke when oxygen doesn’t reach lung and brain tissue.”

Ms. Muhammad explained one of her biggest bouts with Sickle Cell Disease resulted from natural stress students experience while studying and taking exams.

“It made sense. I’m in college, carrying 18 credits, and a biology major. Everything stressed me out,” she said.

Over the years Ms. Muhammad has had to endure many blood transfusions.

“If my white cell count is too high … I may need a blood transfusion. But the issue with getting a blood transfusion for me, I’ve over the years had so many that my body has received a lot of antibodies.”

She explained that she has to be careful who she receives blood from. “What that means is I have to be very careful … I need blood from people who are of the same ethnicity (or race) so my body doesn’t reject the blood, and I don’t have a lot of dangerous complications—a delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction.”

According to medscape.com this occurs in patients who have received transfusions in the past. These patients may have very low antibody titers that are undetectable on pretransfusion testing, so that seemingly compatible units of red blood cells are transfused. This could be potentially life-threatening in people with Sickle Cell Disease.

Ms. Muhammad explained her growing advocacy included increasing blood doners in the Black community. “This has been very important because we don’t have a history of donating blood. And that just goes hand-in-hand with all the medical racism and biases that we’ve had to endure inside of these medical institutions,” she explained.

“That has to change because many of us are the main recipients. Because if you don’t have a pool of Black blood donors to draw from then you risk having to get blood from someone not of the same ethnicity or race.” Transfusions could come with “complications.”

The idea for the foundation came after a tragedy. “The Crescent idea came into existence in 2017, the result of the death of a really dear friend who passed away, the result of SCD complications. She was 28 years old when she passed away from Sickle Cell complications,” said Ms. Muhammad.

“Her passing rocked the Sickle Cell community because she was an important pillar, and we all grew up together. We all went to camps for children with Sickle Cell. So, we were already familiar with each other and kept in touch with each other as adults,” she said.

“There never has been a (local) organization that supported the needs of adults with SCD. We knew the things that we needed that we weren’t getting that weren’t being provided. And during our time of grief, we had to turn right back to our pediatric institutions and that was Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. That was because they had become our family. They had become a medical team that we trusted, more than the adult medical teams that we were receiving medical care from,” continued Ms. Muhammad.

“So, they really put the batteries in our backs to do for ourselves. They told us that we were the ones that would have to take the lead in dealing with the Black community’s Sickle Cell Disease problem.”

Crescent Foundation includes, among other health-related services, psychosocial and case management support to individuals with the disease. “Our Community Health Workers are community liaisons who support patients and families in better managing their medical and social needs until goals are reached as defined by the individual,” said Ms. Muhammad. “This includes making home and community visits in person, virtually or telephonic, connecting families to community resources, and supporting the communication of the individual’s needs with the healthcare team.” For more information visit: www.crescentfoundationscd.org.