Black neighborhoods in the U.S. are in a state of emergency and it is past time to sound the alarm. The historic systematic practice and policy of pushing Blacks out of neighborhoods to make those areas wealthier and Whiter through gentrification has never gone away and only drastic measures can stem the tide of what some view as an ongoing sinking ship of Black homeownership and wealth creation.

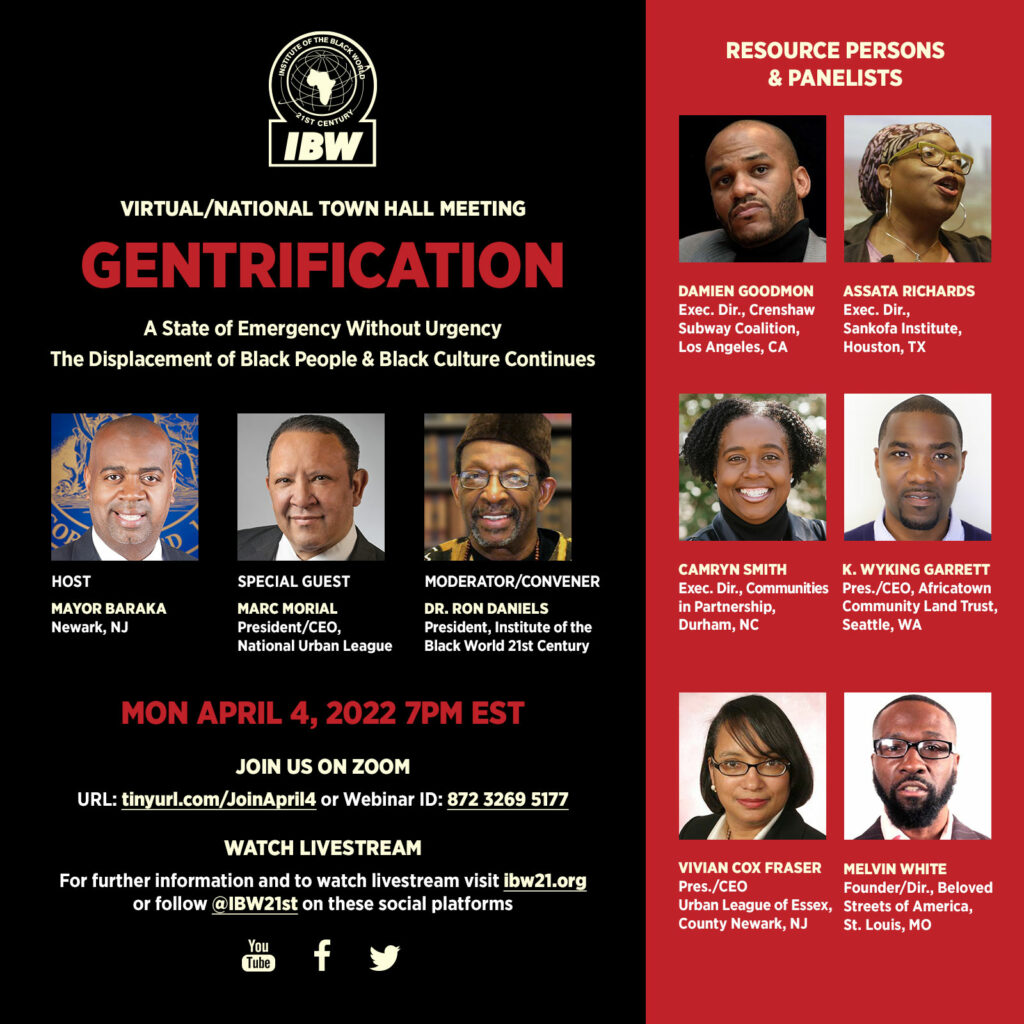

Recently, Institute of the Black World 21st Century hosted a virtual town hall meeting raising the alarm to confront the reality of Black America’s displacement from long established urban communities throughout the country.

The meeting included a variety of panelists in areas of real estate, business, politics, and other areas of expertise under the theme, “Gentrification: A State of Emergency Without Urgency, the Displacement of Black People & Black Culture Continues.”

Dr. Ron Daniels, political science scholar and president of IBW21, opened the livestreamed event to raise awareness about Black people’s housing vulnerabilities.

Marc Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League and former mayor of New Orleans, agreed that gentrification is displacing Black people and their cultures in cities across the country and that dismantling Black communities erases the evidence of their contributions and unique historical narratives.

“Gentrification is part of a trend which has been in place since the 1950s,” he explained. Mr. Morial descried today’s reversal of ‘White flight’ following Black migration from the rural South to America’s urban centers in the wake of World War II. “We want America’s urban communities to be vibrant and strong, but we don’t want it to take place at the expense of residents who built these communities, who struggled in these communities, and hung-in these communities when others left these neighborhoods behind,” Mr. Morial said.

“We need to have a response and a plan as market forces raise the prices around the country,” said Newark Mayor Ras J. Baraka, son of the famed poet Amiri Baraka. “We have to have every deliberate and intentional counter-strategy to mitigate this for working people and poor people in these cities with a sense of urgency.”

Gentrification is a powerful force for economic change in cities, but it is often accompanied by extreme and unnecessary cultural displacement, noted the National Community Reinvestment Coalition in its 2019 report, “Shifting neighborhoods: Gentrification and cultural displacement in American cities.” The report identified more than 1,000 neighborhoods in 935 cities and towns where gentrification occurred between 2000 and 2013. In 230 of those neighborhoods, rapidly rising rents, property values and taxes forced more than 135,000 residents to move away.

“While gentrification increases the value of properties in areas that suffered from prolonged disinvestment, it also results in rising rents, home and property values. As these rising costs reduce the supply of affordable housing, existing residents, who are often Black or Hispanic, are displaced. This prevents them from benefiting from the economic growth and greater availability of services that come with increased investment,” the report notes.

The report also stated that seven cities accounted for nearly half of the gentrification nationally: New York City, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Diego and Chicago.

Problems and agendas

For years, residents in South Los Angeles leveraged their unity to gain concessions regarding layout of a $1.7 billion light rail system, demonstrating how Black neighborhoods, businesses and institutions could influence social, economic, and political decisions effecting their communities.

Damien Goodmon, executive director of the Crenshaw Subway Coalition, said his city is now being “Columbused,” or colonized under the auspices of White capital investments. However, he pointed out, continuous activism and community engagement contributes toward acquiring a better quality of life for residents, he argued.

“I am in the center of Black Los Angeles, a place and space where many fled the segregated South and came to in hopes of a better future,” Mr. Goodmon said. “We have the unfortunate distinction, today, of being the hottest real estate market in one of America’s most unaffordable cities.”

Insisting that the market is doing just as it was intended to do, Mr. Goodmon stated that in the case of Los Angeles county, Blacks have been the only population whose numbers will continue to dwindle into the foreseeable future. “The market is succeeding, it is a process of divestment and replacement for those who are vulnerable, because we have been systemically robbed of the opportunity to create stable communities,” he said. “It’s about power, and we have a right to self-determination.”

Sajdah Wendy Muhammad, an urban historic preservationist and real estate developer, has overseen projects from sub-Saharan Africa to various locations across the United States. One of her most recent projects includes the acquisition and restoration of the South Side Chicago home of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad of the Nation of Islam.

Ms. Muhammad told The Final Call, that the basic definition of gentrification is “replacing an existing ethnic community with another ethnic and socio-economic community.” She explained how relocating manufacturing jobs from downtown areas to suburban areas effect targeted populations. Black America’s working, middle and educated classes left to follow opportunities, often leaving behind impoverished neighborhoods and that over time became prime real estate opportunities for developers, she continued.

“It was nice to be able to say (one) just lived 10 or 15 minutes from downtown or on a shoreline,” Ms. Muhammad stated. “In most cities, those areas were heavily populated with Black people who had migrated through the Great Migration from the South, (but) now that those properties and that land have been revalued, and considered to increase in value, the idea is to remove what is there, but what’s there?” she asked. “It’s Black people.”

A disappearing urban reality

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Houston is the country’s fourth largest city and demonstrates additional challenges as its population trended upward from just over two million in 2010 to over 2.3 million by 2020. An increase of 300,000 people within 10 years and growing housing demands tightened the local real estate market where the median cost for a single-family dwelling topped $328,000, the Houston Association of Realtors (HAR) reported this year.

“This is beyond a state of emergency, as our communities are hemorrhaging, Black people are disappearing, day-in-and-day-out from our communities, particularly here in Houston,” asserted Ms. Assata Richards, executive director of the Sankofa Institute and a third-generation resident of the city’s Third Ward.

“Independence Heights, from 2000 to 2008, lost 45 percent of its Black population. Black people have disappeared literally overnight,” she declared.

Dr. Abdul Haleem Muhammad has a Ph.D. in urban planning and environmental policy. He is the Southwest Regional Student Minister of the Nation of Islam based at Mosque No. 45 in Houston. He told The Final Call that Houston is unique from other major U.S. cities because of its lack of land-zoning ordinances and rules regarding property division.

“As long as a residential development does not have what are called deed restrictions or restrictive covenants, then you literally are free to build whatever you want to build as long as it follows the building codes or the city code,” Dr. Haleem Muhammad said referring to individual lots bought, sold and subdivided by developers.

“So, what normally would be a $100,000 house can now (become) a million-dollar property because (it’s) got four $300,000 condominiums on that same lot. Now, what does that do?” Dr. Muhammad asked. “The market values go up on these properties and the tax appraisal rate goes up.”

During the April 4 virtual town hall, Assata Richards shared slides of Houston’s 10-acre Emancipation Park, founded by four formerly enslaved Africans in 1872. Ms. Richards said its preservation as a cultural site is now threatened, as well as neighborhoods originally founded by Black people, as townhouses and other recent constructions continue to encroach upon other historically Black neighborhoods in the city.

“On a given day, you will see demolition and the removal of people,” Ms. Richards stated. “There is an enormous amount of work on group shock, on the depression, the severing of social relationships, (and) the harm to mental and physical health that African Americans face when they are displaced forcibly from their communities.”

Durham, North Carolina, is no different, according to Camryn Smith, executive director of Communities in Partnership there. Explaining how her city’s once thriving Black business district and the historically Black Hayti community were intentionally destroyed in the late 1960s by building a state highway through the heart of Durham’s Black community, she said, those areas never recovered from their loss. “We’re going to have to have some real means of reparative funding,” Ms. Smith said. “If repair is not at the central focus of what we’re dealing with, we do not have a chance.”

Solutions and strategies

K. Wyking Garrett is a third-generation resident of Seattle’s Central District. He serves as president and CEO of the Africatown Community Land Trust. He shared with the town hall audience how unity and perseverance create models of community-building where determination leads to self-sufficiency and can transform neglected neighborhoods into enclaves of productivity and prosperity.

“When we speak about Africatown, it is really more than an organization,” Mr. Garrett explained. The concept is about making a space to display and honor the beauty and brilliance of a broad Black experience regardless of geographic location, he explained. Mr. Garrett described the legacies of Black pioneers such as William Grose, who traveled to Seattle during the American Civil War and later established the Central District by purchasing 12 acres of land as a settlement for freed slaves in 1882.

The Central District eventually grew to become a mecca for Black excellence and entrepreneurship West of the Mississippi. Mr. Garrett added, that the continued displacement of Black people by the early 2000s drastically reduced the city’s Black population. “When we looked at the comprehensive plan for the city of Seattle, we did not see our future … so our goal was to not just accept that, but to create our own planning process, Black Seattle 2035.”

Founded in 2016, Africatown CLT (Community Land Trust) works to “acquire, develop and steward land in Seattle’s Central District to empower and preserve the Black Diaspora community,” noted neweconomynyc.org. In 2019 the group completed its first project in the historic Liberty Bank Building, providing 115 units of deeply affordable housing and three commercial spaces for Black-owned businesses, the website noted. “Africatown made headlines when, in the wake of protests over police brutality and racial injustice, the City of Seattle agreed to transfer ownership of several properties to the CLT and other Black-led organizations.”

Vivian Cox Fraser, president and CEO of the Urban League of Essex County in Newark, New Jersey, described the evolution her organization is making from one focusing primarily on social services, to one placing more of an emphasis on economic development and property ownership.

“About 10 years ago, we started pivoting our work toward being more comprehensive, where the Urban League sits at the intersection of people and place, (and) as we started looking at the development that was going on in our community, we wanted to get engaged and that is when we started fighting with the city,” Ms. Cox Fraser told town hall participants.

According to wbgo.org only about 20 percent of Newark households are homeowners so Urban League of Essex County with public and private funding, began building and renovating two- and three-family homes for low-to-moderate income buyers. The homes provide housing for the owners who in turn also become landlords. “All of them are designed to be owner-occupied with rental units,” Ms. Fraser explained in a previous interview on wbgo.org. “And the rental units, that’s how families can afford to purchase the homes because they have tenant income.”

The collective purchase and development of real estate and land in urban areas by Blacks for the benefit of their communities is a way to fight gentrification. The Honorable Elijah Muhammad and the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan have repeatedly taught Black people on the importance of land ownership and to ultimately, “do for self or suffer the consequences.”

Dr. Haleem Muhammad stressed the aim, purpose and support of Muhammad’s Economic Blueprint asks Black wage-earning adults to contribute $1.40 per month into a treasury to begin to address poverty and want that continues impacting Black America.

During his monumental online lecture series, “The Time and What Must Be Done,” Part 30, Min. Farrakhan explained that ownership of land is a prime requisite for freedom and independence.

“America is for sale,” the Minister stated. “But we are not owning it! We helped build this country; our sweat and blood was used to protect it—shouldn’t we be co-owners of it?”