During the Cold War with communism and the old Soviet Union, the American government tried to use jazz musicians to bolster its global reputation and used cultural performances to cover covert operations in Africa.

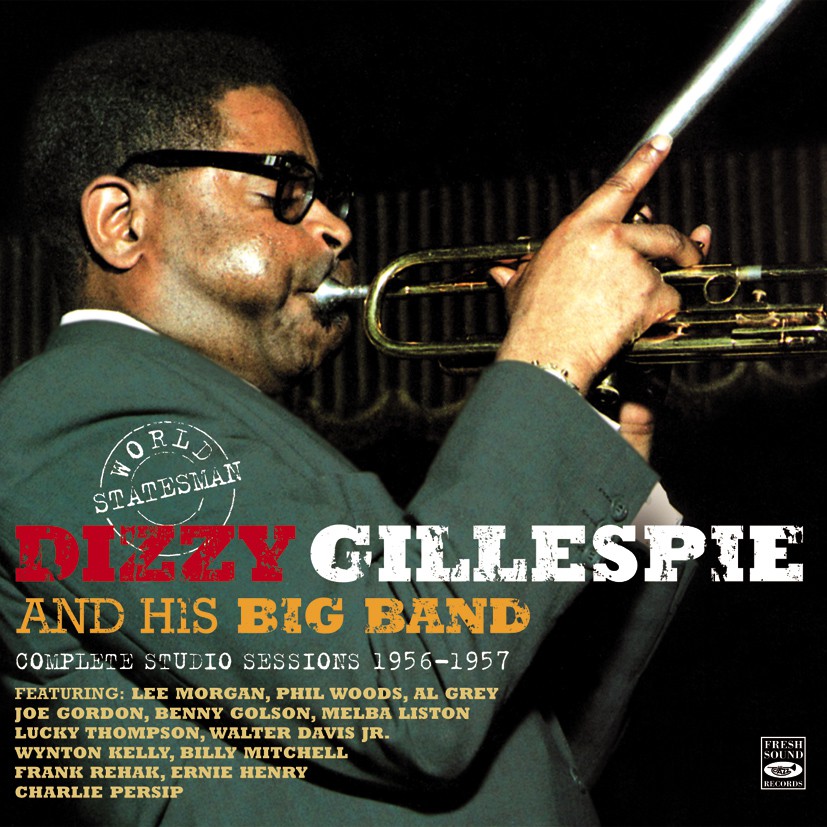

There was often tension between musicians representing American interests abroad while their people suffered at home. The U.S. State Department’s first actual jazz ambassador, Dizzy Gillespie, grew up in the South. He saw the irony of promoting America’s “freedom” abroad whilst remaining a second-class citizen.

Known for being outspoken, he refused to be briefed by the State Department before a performance, reported Time.com.

“I’ve got 300 years of briefing,” he said. “I know what they’ve done to us and I’m not going to make any excuses.”

In Fayetteville, Arkansas, the University of Arkansas houses information about the American jazz musicians and their roles as cultural ambassadors. Significant information is found in “the collected papers of J. William Fulbright, a long-serving senator from Arkansas and architect of the Fulbright scholarships, the U.S. government exchange program he founded in 1946.

By some clerical quirk of fate, Fulbright’s archives include a huge number of documents relating to the U.S. government’s ‘cultural presentations program’—the effort to export American culture as a weapon in the fight against Soviet communism,” reported The Guardian newspaper.

In 1954, President Eisenhower wrangled $5 million from Congress to send U.S. cultural groups abroad as part of the growing “public diplomacy” including symphony orchestras, theatre groups and folk dancers. The Soviets responded by touring national institutions such as the Kirov and Bolshoi ballet troupes.

In 1956, Harlem Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., suggested sending the country’s greatest jazz musicians overseas as cultural emissaries. He convinced his friend, jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, to become America’s first jazz ambassador.

The State Department believed touring mixed-race jazz groups could deflect attention from spiraling civil rights battles and protests, while presenting a uniquely American art form the Russians couldn’t touch. And, as a deluge of fan mail from Voice of America radio attested, jazz was immensely popular with international audiences.

In October 1960, trumpeter Louis ‘Satchmo” Armstrong left the U.S. for a two-month tour of Africa in his role as jazz ambassador.

Three years prior he refused a U.S. sponsored tour of the Soviet Union. He discovered on September 2, 1957, that the governor of Arkansas, utilizing the National Guard, blocked entry of Black American students to integrate public schools.

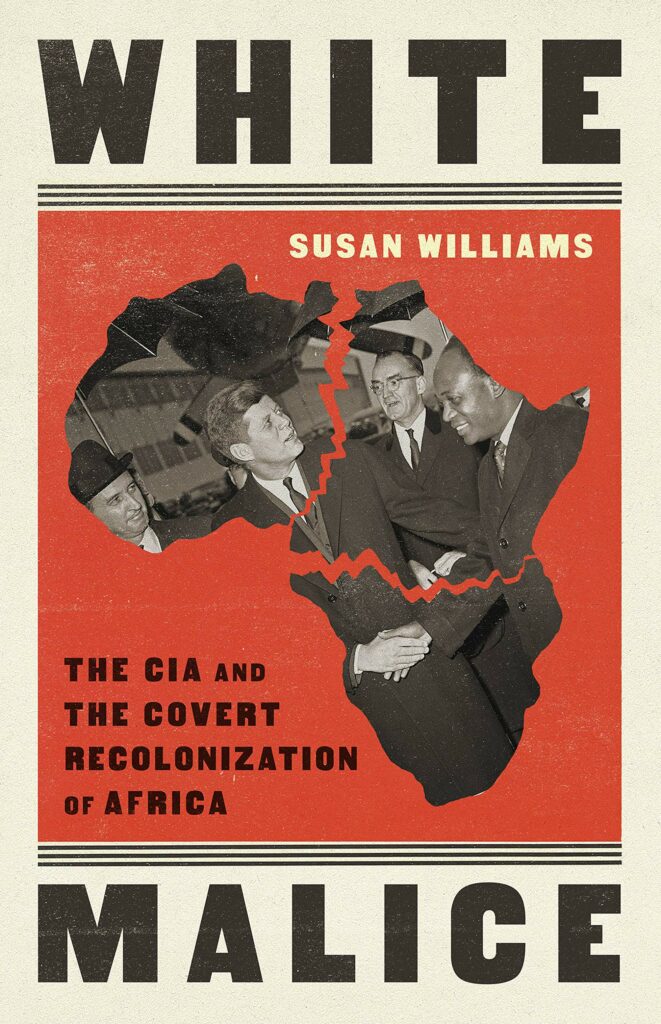

According to Susan Williams’ 2021 book, “White Malice: The CIA And The Covert Recolonization of Africa,” Armstrong became “deeply upset, became furious, the U.S. government refused to enforce the integration of the school as required by a federal court order. He denounced Eisenhower as being ‘two-faced’ on civil rights and having ‘no guts.’ ” Armstrong added, “It’s getting so bad, a colored man hasn’t got any country.”

Armstrong’s 1960 Africa tour included Accra, where he performed at the Old Polo Grounds to an audience of nearly 100,000 people. Armstrong went on to Nigeria, joining celebrations of Nigeria’s independence from Great Britain.

Weeks later, on the morning of Oct. 28, musical great Armstrong and his All Stars arrived in the Congo’s Leopoldville. The tour was not, as in previous engagements, sponsored by Pepsi in competition with Coca Cola for control of the African market. The Congo tour was sponsored entirely by the U.S. State Department.

Armstrong’s next stop on the Congo tour was Elisabethville. “It was an odd arrangement since the succession of Katanga had not been recognized by the U.S. ‘For reasons that escape us in the embassy,’ ” wrote CIA station chief Larry Devlin.

The U.S. Information Agency had Armstrong “play in Elisabethville, capital of the so-called Independent State of Katanga.” The CIA and high-level State Department officials used Armstrong’s visit to Katenga as a way to visit and monitor goings on without undue suspicion.

Katenga contained very large copper mines, very rich uranium deposits and important diamond mines. Belgium, the U.S and the UK, all having mining interests in Katanga, balked at the idea of a Congo lead by a government allied with Soviet Union and run by Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. With the support of President Dwight Eisenhower, the order was at all costs to guarantee control of the region’s mineral and natural resources.

Follow @jehronMuhammad on Twitter.