Dubious U.S. meddling in Africa is being played out in Ethiopia as bloodshed and mayhem have gripped the Horn of Africa country since November 2020.

The conflict depicted as a civil war is layered, nuanced, and further complicated by American involvement under the pretext of making peace.

President Joe Biden is beefing up U.S. military personnel by sending 1,000 National Guard troops from Virginia and Kentucky into the Horn of Africa. The move comes as hostility in Ethiopia has potential to spread across the region. The deployment of Guardsmen to “unspecified countries” is slated for early next year.

Analysts told The Final Call the U.S. presence is dedicated to pursuing America’s interests in the Horn of Africa, not what’s in the best interests of African countries.

While current tension is touted as civil war between the Ethiopian government and the Tigray Peoples Liberation Front, America is playing a role in the conflict, explained Ajamu Baraka, national organizer for the Black Alliance for Peace, a U.S. anti-war and human rights organization.

The U.S. wants to influence military activity, politics and economics in the Horn of Africa, which means containing Ethiopia as a potentially uncontrolled regional power, said Mr. Baraka, a longtime human rights activist and organizer against U.S. imperialism.

Aiming to undermine the Ethiopian government, the U.S. has supported the Tigray rebels and the ruling class of Ethiopia’s northern region, he continued.

When the U.S. pushes “reconciliation” between the warring groups and the Ethiopian government, its goal is to force the Abiy Ahmed regime to share power with the pro-American TPLF and protect Washington influence, Mr. Baraka said.

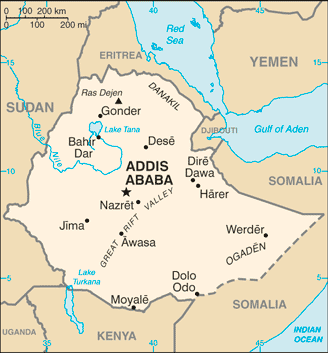

The Horn of Africa is important because of its proximity to strategic choke points and major trade routes through the Red Sea and important shipping corridors like the Bab al Mandab Strait, access to the Middle East, Indian Ocean, and South-East Asia.

Africa facilitates one-third of the shipping between North America and Asia, and one-third of global oil shipping. U.S. and global security depend on unhindered access to these waters. Ethiopia has a fast-growing economy and the U.S. fears an unbossed African power in the region, said analysts.

“They want to prevent the emergence of an independent regional power,” said Walter Smolerek of the U.S.-based ANSWER Coalition. That means regime change in Ethiopia similar to the ouster of Muammar Gadhafi in Libya, who America saw as an enemy and threat to her moves in Africa and the Middle East, analysts said. Western intervention in Libya in 2011 and the murder of Col. Gadhafi turned Libya into a failed state as the U.S. rid itself of a leader the U.S. decided was an enemy.

America’s allies and partners, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia, also want to marginalize Ethiopia and thwart a major dam project involving the Nile River. Ethiopia’s $5 billion project on the Blue Nile River has raised concerns about water security for several countries. It has exacerbated tension between Ethiopia, Egypt, and the Sudan.

Negotiations are at a stalemate increasing anxiety over more possible military conflict in the already volatile region.

In addition, Ethiopia’s neighbor Djibouti hosts the headquarters of AFRICOM, the U.S. African Command, as well as China’s first foreign military base.

Another concern the U.S. has in the Horn of Africa is tied to competition with its rival power China on the Motherland, observed Mr. Baraka. China is Ethiopia’s top trading partner, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity, an online trade and economic data platform. The U.S. lags behind China in the great power competition for business and influence in Africa. According to the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, annual U.S. foreign direct investment in Africa has been dwindling since 2010.

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia has been engaged in a more-than-a-year war with rebel forces in its Northern Tigray region. The war has killed thousands and displaced hundreds of thousands of people.

“We have to push the scattered enemy to surrender,” declared Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in early December. Mr. Ahmed made the remarks after returning from two weeks on the war’s frontlines. The Ethiopian government claimed it recaptured major territory from the TPLF—once a ruling party—but now considered an insurgent group. The ruling government’s victories came after months of land takeovers by the TPLF.

“Ethiopia is safeguarded by her gallant children. Ethiopia might be tested, but it is impossible to defeat Ethiopia. Ethiopia will not be defeated today and tomorrow too. The name Ethiopia is always associated with victory,” declared the prime minister.

In recent reports, the TPLF claimed it was not defeated but made a strategic retreat.

The Ethiopian government announced Dec. 12 that Mr. Abiy, a 2018 Nobel Peace Prize winner, returned again to the battle front to lead military campaigns to regain territory lost in the Amhara region. Since the war started defense forces and militias from several Ethiopian regions were drawn in as were troops from neighboring Eritrea.

The basic Western narrative says its Africans killing Africans in a volatile mix of ethnic hostility. But for Ethiopians, an ancient people, it is more complex.

“The essential historical context is always missing when we hear politicians talk about it or read it in the mainstream corporate news,” argued Mr. Smolerek of the Act Now to End War and End Racism (ANSWER) Coalition.

The conflict can be understood in the history of how Ethiopia was constructed as a nation state composed of various ethnic groups cobbled together. Ethiopia is a federation of 10 regions, largely along ethnic groups, vying to influence the country’s power equation. Most prominent is the Tigray People’s Liberation Front which dominated Ethiopia politics for nearly 30 years. The group was sidelined when Mr. Ahmed came to power in 2018 and moved to bring together fractured ethnic groups across the country.

The Tigrayan fighters are aligned with the Oromo Liberation Army, a group fighting for greater rights for ethnic Oromos, who are 35 percent of Ethiopia’s 110 million people. Tigrayans make up about 6 percent of the population.

Ethnic driven strife among groups including the Oromo, Amhara, Tigray, and Somalis resulted in violent clashes that intensified this year.

Ethiopia is composed of groups that still see themselves as independent peoples based largely on ethnicity and group politics. While some have integrated into the Ethiopian state, tensions have arisen periodically. Groups often see themselves as being disadvantaged or deprived of power, opportunity and progress.

“Those differences could be played on from time to time by imperialism,” said Mr. Baraka.

President Joe Biden has revoked Ethiopia’s privileges under the African Growth and Opportunity Act, effective January 2022. AGOA is a U.S. trade pact allowing imports of African products into the U.S. duty free.

Both warring parties are suspected of rights violations, war crimes, and atrocities. The Human Rights Council announced Dec. 17 a special session would be held to address the “grave human rights situation in Ethiopia.” The special session was convened following an official request submitted by the European Union.

Ethiopia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs had called on ambassadors of African countries in Addis Ababa to protest the special session. Yoseph Kassye, director-general for International Organizations at the ministry, said Africans should continue to be committed to African solutions to African problems. African countries need to jointly resist undue external pressures and attempts to meddle in their domestic affairs, he said.

Framing the crisis as “ethnic conflict” with “impending famine” is a pretext to justify sanctions and possibly a “humanitarian” military intervention, noted observers.

Earlier this year the U.S. began restricting visas for Ethiopian government and military officials. The restrictions also include far-reaching constraints on economic and security assistance to Ethiopia.

In November, Washington imposed economic sanctions on the military and ruling party of Eritrea. The U.S. Department of Treasury cited “massacres,” “looting,” “sexual assault” and blocking humanitarian aid by Eritrean forces. Critics say the stance is hypocritical.

“The United States does not have some altruistic interest in humanitarianism … they’re solely concerned about their power in the Horn of Africa,” said Mr. Smolorek.