by Naba’a Muhammad and Brian E. Muhammad

The Final Call @TheFinalCall

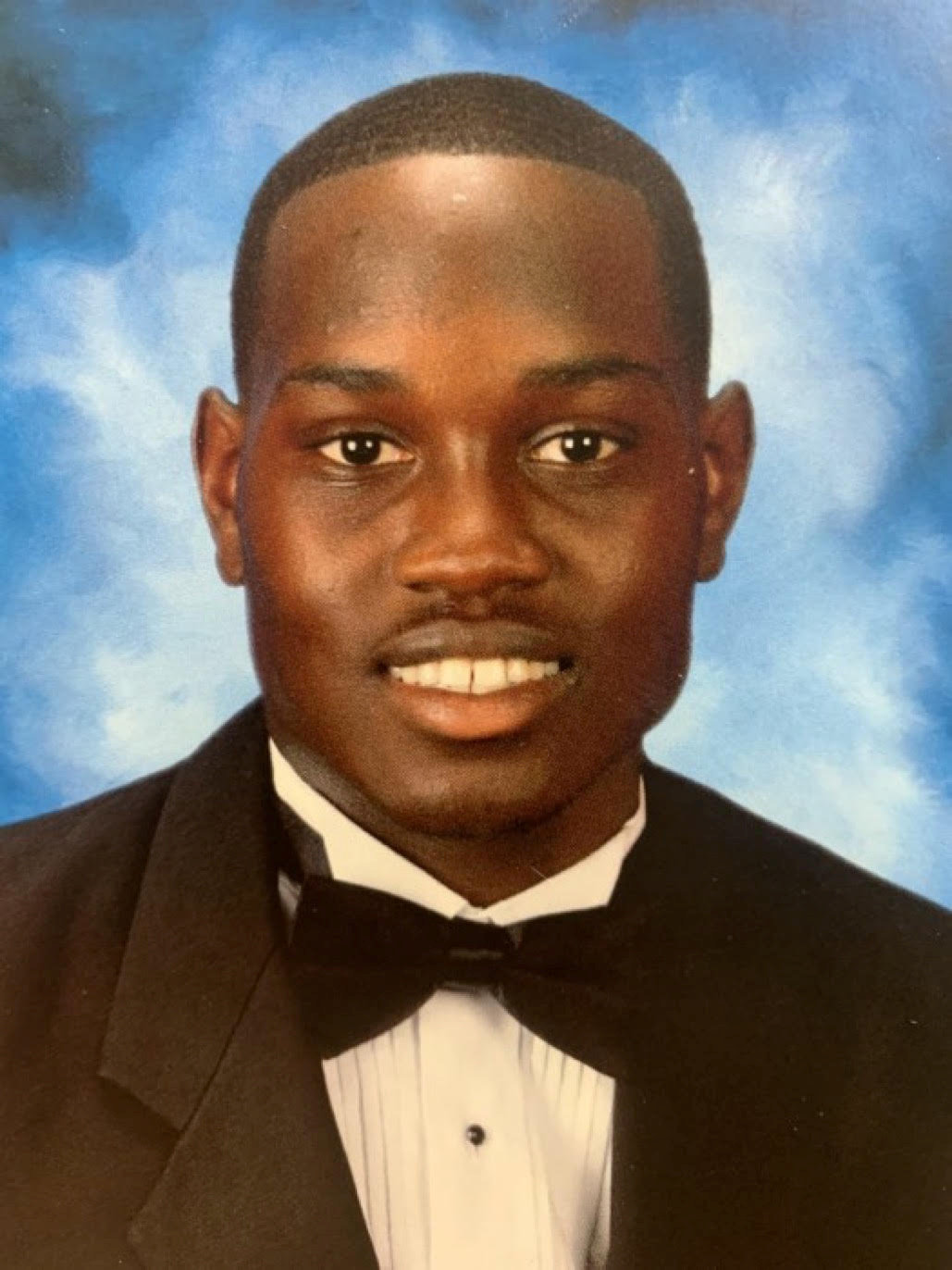

There is nothing perhaps as deep and as lasting as a mother’s love, a mother’s pain and a mother’s determination to defend her child even in death. Wanda Cooper-Jones devoted such commitment to a quest for justice for her youngest son. She called her boy “Quez,” short for Marquez—his middle name.

“Today’s a good day,” Ms. Cooper-Jones told The Final Call in an exclusive telephone interview, hours after those responsible for her son’s death were convicted of murder.

Quez is known to the world as Ahmaud Arbery.

Ms. Cooper-Jones fought when there were no signs anyone would be held accountable for her son’s killing. Prosecutors in Glynn County, Ga., where her son died had already refused to file any charges. She found strength and resilience in her faith.

“I have my struggles from day to day … I had many, many trials early in my younger life,” Ms. Cooper-Jones shared. “There was nothing I could send to God, that he didn’t fix it for me.”

“And then when Ahmaud was murdered, I prayed and I prayed and I knew God would come through for us, ” the mother of three continued.

Ms. Cooper-Jones admits it took a while to get to this point of a victory. “I never saw this day,” she said. But she clung to faith in God’s timing and something “good” eventually happening.

She still takes it day by day. She has a message for mothers dealing with similar horrific losses. “Keep pushing, don’t give up hope, continue to pray, continue to trust God because God won’t fail you,” said Ms. Cooper-Jones.

She is trying to stay strong for a federal civil case against her son’s killers, Travis McMichael, 35, his father Gregory McMichael, 65, and neighbor William Bryan, 52, who were found guilty of murder and other related charges on Nov. 24. All face mandatory life sentences and separate federal charges, including hate crimes and attempted kidnapping on the streets of Satilla Shores, Ga., on February 23, 2020.

Earlier this year, she filed a civil suit against the McMichaels, Mr. Bryan, several county police officers, former Glynn County Police Chief John Powell, and former district attorneys Jackie Johnson and George Barnhill.

The suit charges the district attorneys and police covered up what happened to her son. It charges the killers “willfully and maliciously conspired to follow, threaten, detain and kill Ahmaud Arbery.”

The lawsuit has not been heard in court yet. The federal trial is scheduled for February 2022.

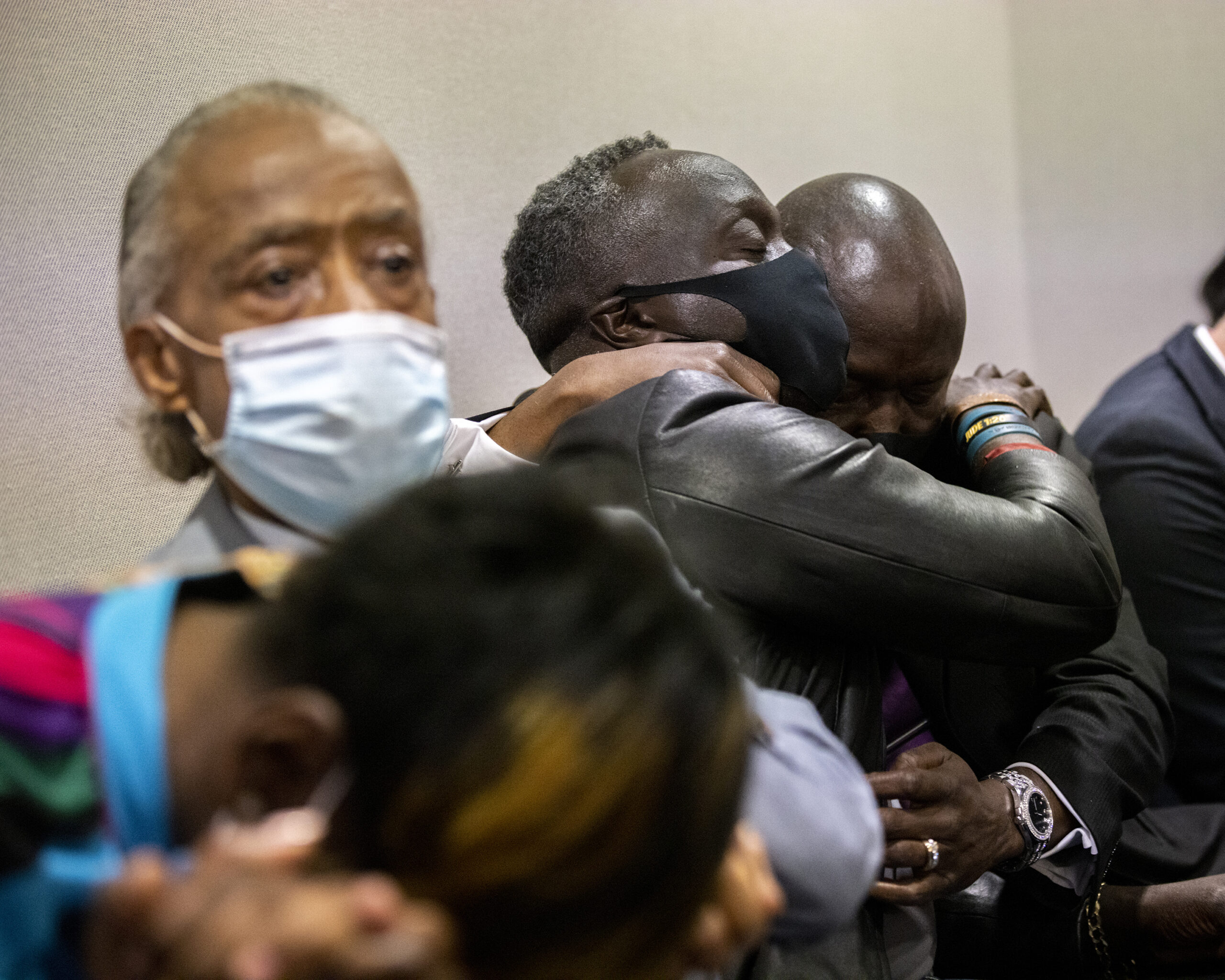

“We conquered that lynch mob,” said Marcus Arbery, Ahmaud’s father, addressing those gathered outside the Glynn County Courthouse after the verdict.

Many felt jubilation and relief with the guilty verdict rendered by 11 White and one Black juror.

The outcome was never guaranteed with defense attorneys lobbing appeals to race at jurors through complaints of “intimidating” Black ministers in the courtroom, ugly depictions of Ahmaud in defense lawyers’ closing arguments and references to how people in Scintilla Shores, a predominantly White community, looked out for one another and kept one another safe. Ahmaud was described as an intruder whose presence and visit to a house still under construction violated the community.

It was 74 days before any arrests were made, and only after video of the shooting went viral.

With the police slayings of Breonna Taylor, a Black woman in Louisville, Ky., and George Floyd, a Black man murdered by a White cop on a Minneapolis street, protests grew. Ahmaud’s name was added to the list of Black martyrs whose lives were taken by Whites in America.

Lynching in America

“Some people likened the murder of Ahmaud Arbery to a modern-day lynching, but I see it as simply a lynching,” said James Simmons, a human and civil rights attorney. “They saw fit to chase him down—in the old term, coon hunting—and gun him down,” said Atty. Simmons.

Lynching is defined as a killing by three or more people claiming extrajudicial reasons to kill. Ahmaud, a lone, unarmed Black man on a jog, was illegally confronted by armed White men in South Georgia. Historically that is a lethal combination.

Georgia is stained with White racial terror and a lynching tradition second only to Mississippi in numbers between 1877 and 1950, according to the Equal Justice Institute. “For more than six decades, as Southern Whites used lynching to enforce a post-slavery system of racial dominance, White officials outside the South watched and did little,” an EJI report observed.

There was fear Ahmaud’s killers, who pursued him in pickup trucks and trapped him before Travis McMichael shot him to death with a shotgun, would be protected by the White power structure and legal system. Without the mother’s vigilance, the death video, protests, media coverage and anger nationwide, it’s unlikely that the case would have ever gone to trial.

“This is the beginning of an era of new justice that we can continue to use as a blueprint,” said Porch’se Miller, a national civil rights activist from Atlanta.

“As you know 99 percent of the time it comes back with an unfavorable verdict—justifiable homicide,” said Cephus “Uncle Bobby” X Johnson of the Love Not Blood Campaign. He advocates for families seeking justice for loved ones lost to police or community violence.

Though “extremely surprised” and “grateful” about the verdict, he hadn’t had a lot of faith in the jury make up as he sat in the courtroom. He is the uncle of Oscar Grant III who was killed by a California transit cop on New Year’s Day 2009.

“The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan said with change, there is two elements, danger, and opportunity,” said Odis Muhammad of the Nation of Islam study group in nearby Brunswick, Ga. “What is happening in America and the world is the grip of White supremacy has been loosened and is falling.”

Things happening in Georgia illustrate an unraveling of White power, he continued. “When their world begins to disintegrate in front of their eyes, desperate moves are necessary,” said Mr. Muhammad. He added that Whites feel, “We gotta do some things to put y’all (Blacks) back in check, we have to make sure that we are the dominant force and that you all respect that.”

“As the Honorable Elijah Muhammad said, ‘this man will go down fighting’ with his last breath,” said Odis Muhammad.

National pressure, local change?

“What we’re seeking is real change … with the police department … the justice system locally,” commented Allen Booker, a Glynn County commissioner who knew Ahmaud as a young man working for his father in landscaping.

National attention added pressure for local change, he said.

“I think that transparency is our friend,” said Mr. Booker. “It’s not something happening backroom or underhanded that you’re trying to seek, but real justice,” which ultimately “comes from God,” he added.

The commissioner and others have worked to reform the county justice system. They organized to remove discredited Police Chief Powell. They fought to get rid of former District Attorney Jackie Johnson. She was arrested in August for telling two police officers not to arrest the McMichaels over the killing.

Ms. Johnson was indicted on violating her oath of office, a felony, for “showing favor and affection” to Gregory McMichael and failing “to treat Ahmaud Arbery and his family fairly and with dignity.” Gregory McMichael was a former cop and worked with Ms. Johnson as an investigator for the Glynn County district attorney’s office.

Mr. Booker hopes positive change will come with the appointment of Jacques Battiste, the county’s first Black police chief, and his deputy, Ricky Evans, who is also Black.

Gains attributed to the Arbery case include Georgia repealing a citizen’s arrest law, and a new law barring non-law enforcement from detaining people. Georgia also became the 47th state to enact a hate crime law.

But more needs to be done. “The federal government still has not passed federal anti-lynching legislation, despite over a hundred years of advocacy for it,” noted Atty. Simmons. If the federal government were serious about stopping racist activity it would pass police reform, anti-lynching and voting rights protections, he said.

“That’s three guys … White men. That is not covering the country,” added Atty. Simmons. “There are still people from sea to shining sea that want to engage in this activity.”

History and old hatred?

Atty. Simmons wouldn’t be surprised if lynchings and racial animus increase. Although, there were convictions in Georgia, there was the acquittal of Kyle Rittenhouse, who shot three White men, killing two, during police protests in Kenosha, Wisc., last year. The White right and White terror organizations supported the young White male.

“There is so many Ahmaud Arberys’ in small towns like this all around the United States,” said organizer and activist YoNasDa Lonewolf, who lives in the South.

Local government didn’t care about the case, she noted. It was the movement of the people that kept the spotlight on and led to the trial and the verdict, the activist added. “We cannot flip the supremacy that is happening if we don’t speak up. We cannot be silent anymore,” said Ms. Lonewolf.

There was widespread joy, tempered joy across Black America with the convictions and declarations from some Blacks and Whites on the right that the system worked. Few were declaring a new day in the United States.

“Generations of Black people have seen this time and time again, with the murder of Emmett Till, Trayvon Martin, and many others. The actions and events perpetrated by the McMichaels and William Bryan leading up to Ahmaud’s death reflect a growing and deepening rift in America that will be its undoing if not addressed on a systemic level,” warned the NAACP.

“We must fix what is genuinely harming our nation: White supremacy. To address and begin to repair the harm and trauma caused by centuries of racism, violence, and murder, we need stronger federal and state actions to address and eliminate outdated racist policies, like citizens’ arrest.”

Odette Flemming, who lives in the St. Louis area which has its own ugly racial history and where protests and rebellion erupted after the 2014 police killing of unarmed Black teen Mike Brown, was plainspoken. “These guilty verdicts are a direct result of the digital age. If no video footage had ever emerged, Ahmaud Aubrey’s family would never have even seen the inside of a courtroom,” she said.

“There is nothing Black people can do to minimize these attacks since they are unprovoked. Therefore, as long as we are dark skinned people in America, we are potentially at risk of being the victim in an unprovoked attack. That is the American reality that remains hidden and is forgotten every time an innocent life is taken and the White majority culture seeks to justify the death by digging for the imagined past sins of the victim and never the predator,” she said.

Cedric Rashad is a 73-year-old successful businessman. Born in Mississippi, now living in Mazatlán, Mexico, he picked cotton as a little boy, lived through Black and White drinking water fountains and other indignities.

“I’m so disappointed in how people have become so open with their bigotry, this America has not changed much since I was young,” he said. “We have become so polarized as a country and thought we would be accepted, especially when Barack Obama was elected. But that just pulled the scab off a sore that’s been infected for a long time. I see this country moving backwards not forward.”

J.A. Salaam contributed to this report.