Head prosecutors in two Maryland locations released nearly 150 names of current and former police officers on a “Do Not Call List” their offices will not use in court as witnesses due to their credibility issues.

This type of list has historically been shielded from the public but legislation in Maryland, Anton’s Law, for police accountability that went into effect on Oct. 1 allows the records of investigations into alleged police misconduct to be made public.

“While the overwhelming majority of Baltimore Police Department officers are hardworking, dedicated and trustworthy public servants who decidedly risk their lives every day doing what most won’t, when a police officer is convicted of a crime and/or their credibility and integrity is compromised, it stifles our ability, as prosecutors, to do our jobs and adequately pursue justice on behalf of the communities that we serve,” explained Baltimore City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby in a statement.

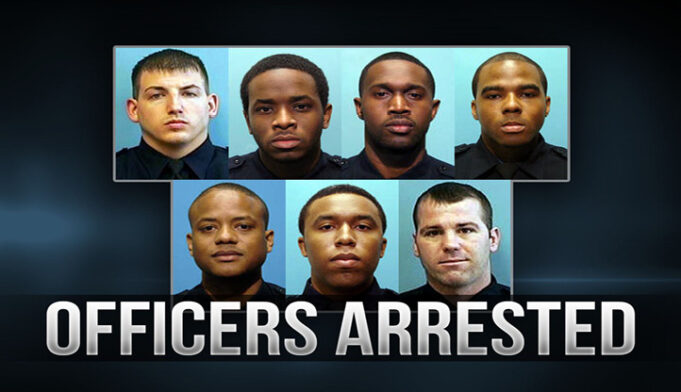

She released 91 names Oct. 29 that are involved in 800 open cases and 300 plea bargains. That number is far fewer than the 305 she cited in 2019 during testimony before the Maryland Commission To Restore Trust In Policing, a state group tasked with investigating the Baltimore Police Department’s Gun Trace Task Force, a major scandal involving police corruption and crime that rocked the city and the state.

Photo: MGN Online

Activists such as the Baltimore Action Legal Team (BALT) believe there are more names and sued Mrs. Mosby two years ago to release the additional names.

“She’s saying she doesn’t feel comfortable releasing the other names because the officers on that list have charges that haven’t been substantiated,” Iman Freeman, BALT executive director, told The Final Call. “When we were in court that distinction was never a concern. The whole time they’ve been telling us that all of the officers had credibility issues, irrespective of whether or not their charges was substantiated.”

“Now, she’s making this distinction between these two lists. We were unaware of this distinction. We are adamant that the list that she released is not the list that we sued for. We’re still waiting to get the list that the court said that they should give us.”

Police union leaders, who are concerned about officers’ rights, said the disclosures could jeopardize due process. Officers still employed, while charged with crimes, have yet to have their cases heard in court. Prosecutors’ powers are limited to deeming officers unfit for testifying in court.

“Police across the nation have more protections than say an average person,” explained Ms. Freeman. “In Maryland there is something called the Law Enforcement Officers Bill of Rights. It gives them more protection then say, you or me would have when it comes to being charged with a crime. They have so many different protections.

“Often times police officers may commit crime, but not be prosecuted. It’s just so many different reasons why they would not be convicted or even charged with crimes and still be on the force,” continued Ms. Freeman.

Braveboy Photo: Facebook/Team Braveboy

Baltimore City is the largest in Maryland with 575,584 residents according to the 2020 Census, 62 percent are Black. The police force is 45 percent White, 40 percent Black and 12 percent Hispanic.

The Baltimore list includes officers from that police department’s now defunct Gun Trace Task Force who pleaded guilty or were convicted in federal court with a wide range of abuse of power charges.

More than 25 percent of the officers on the Baltimore list have pending criminal charges ranging from murder to child pornography to theft. Thirteen have been investigated or have been charged by the police department’s internal affairs division. The employment status is not known for about 10 percent of the officers listed.

“In order to restore trust and strengthen confidence in law enforcement, we must preserve the integrity of the justice system by being transparent and accountable to the communities we serve. The publishing of our ‘Do Not Call’ list once again demonstrates our unwavering commitment to transparency and police accountability in Baltimore City, which is why we lobbied and legislatively advocated to be able to do so,” said Mrs. Mosby.

She is joined by the only other Black female prosecutor in Maryland, Aisha Braveboy in Prince George’s County, with 967,201 residents, 63 percent are Black. The county police force is 45 percent White, 43 percent Black and eight percent Hispanic. P.G. County, which is in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, is often cited as the richest Black county in the world.

Ms. Braveboy and Mrs. Mosby were the only two prosecutors in Maryland to testify in support of Anton’s Law which was part of legislation to make policing in the state fair and transparent.

The legislation was vehemently opposed by police unions, the Maryland Chiefs of Police Association, and was vetoed by Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan. The state legislature overrode the veto.

The bill was named for Anton Black. He was a 19 year old college student killed in 2018 after being restrained by the police. His family spent months trying to find out exactly what happened. This new legislation gives the public—including prosecutors and defense attorneys—increased access to an officer’s complaint history.

Ms. Braveboy, in a press release Oct. 29, spoke highly of officers who work to keep communities and the public safe. “However, holding those officers accountable who risk the credibility of their departments and the integrity of cases brought to the justice system is the job of the State’s Attorney,” she added. “We have a duty and obligation to, not only assess the credibility of each and every witness on behalf of the state, but also ensure that the pursuit of justice includes the bold and necessary reforms our justice system calls for.”

The majority of the 57 officers on the P.G. County list come from the county police department, including 17 officers currently employed there and another 28 who have left. That list also includes 12 officers from smaller municipal departments, the FBI or Maryland State Police.

Twenty officers on the list have been convicted of criminal charges including theft, misconduct in office or violent crimes. Fifteen have pending criminal cases and most others are being investigated by the prosecutor’s office or have been flagged because of cases with their department’s internal affairs division.

“The public has a right to have the best and most professional set of officers protecting and serving them,” Ms. Braveboy said in a media interview. “It is these officers who are racist, who are not telling the truth, who really disrespect the profession, and those individuals have no place on a police department, certainly they don’t have a place on the witness stand.”

The Prince George’s County Police Department released a statement, saying in part, “Of the 17 officers included on the list, seven are under state or federal indictment and suspended without pay, two are on admin leave, and the remainder are assigned to non-public admin positions.”

Activists around the state have long demanded the names of officers on this list be released. When Anton’s Law went into effect the list was made public. Now that the lists have been made public, they will be analyzed to see if any cases that involve these officers will need to be dropped or reopened.

One of the officer’s involved in Anton Black’s restraint had 30 documented use-of-force reports filed against him.

The criteria published by Ms. Braveboy’s office explains that an officer can be included on the Do Not Call list if they tell lies or make misstatements that affect court cases, if they are convicted of certain offenses, or if they act in a manner that demonstrates that they are racist, homophobic, or otherwise biased or prejudiced.

In Baltimore, officers can be added if they are convicted of, or charged with perjury, false statement, any crime involving “deceitfulness, untruthfulness, falsification” or other elements that make their testimony less credible, according to Mrs. Mosby’s office.

“Anything of that nature (like the Do Not Call lists) cannot help but be a step in the right direction,” Nation of Islam P.G. County Student Study Group Coordinator Jamil Muhammad told The Final Call. “The question is, is a step a significant measure of progress? In a county like Prince George’s where police racism, corruption, and competence, has been a problem for generations, there are still many miles to go.”

Baltimore and P.G. County join Philadelphia, Boston, and Brooklyn, N.Y., as some of the jurisdictions that publish Do Not Call lists.