WASHINGTON—City government stakeholders, non-profits, business leaders, and community members gathered recently in the virtual world to discuss how to reduce rising rates of gun violence across the city.

The Zoom meeting devoted to “Strategic Planning for Gun Violence Reduction” focused on developing a roadmap for saving lives. David Muhammad, executive director of the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (NICJR), discussed the results of a June 2021 report, “A Landscape Analysis of Washington, D.C. Community Based Services and Supports.” The report examined current efforts by looking at their intentions, effectiveness and actual delivery of services. The analysis identified more than 100 programs and services in the city that can generally be called violence prevention or youth development.

in Atlanta.

According to the report, the tremendous number of different programs, with overlapping goals and target populations suggest, at minimum, a need for greater coordination and collaboration.

In partnership with the Public Welfare Foundation, NICJR conducted an Analysis of Violence Reduction, Re-Entry, and Youth Development services in the District of Columbia.

The report was also released in June and concluded there was an urgent need to deliver services in a smarter and more effective manner in the city.

Washington experienced a significant increase in violent crime, namely shootings, in 2020. There were 922 people shot in the District in 2020, and 198 homicides, representing increases of 33 percent and 19 percent respectively compared to 2019.

Despite the existence of so many programs and services, those in greatest need and of highest risk are not being served, said the report.

The analysis concluded violence reduction efforts can be broken down into three areas: violence prevention, violence intervention, and community transformation. The report identified how each community organization fits into one of those categories.

The city’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement Family and Survivor Support and Violence Intervention is supposed to “foster community-based strategies to help prevent violence and increase public safety.” It has a budget of $7 million to $8 million, 30 staff members and functions around three initiatives, the Pathways Programs, the Violence Intervention & Prevention Program, and Family & Survivor Support Services.

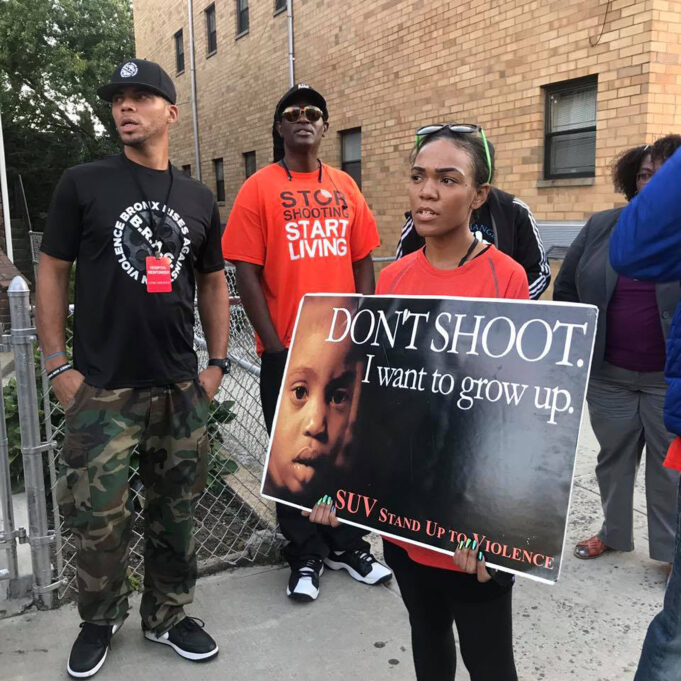

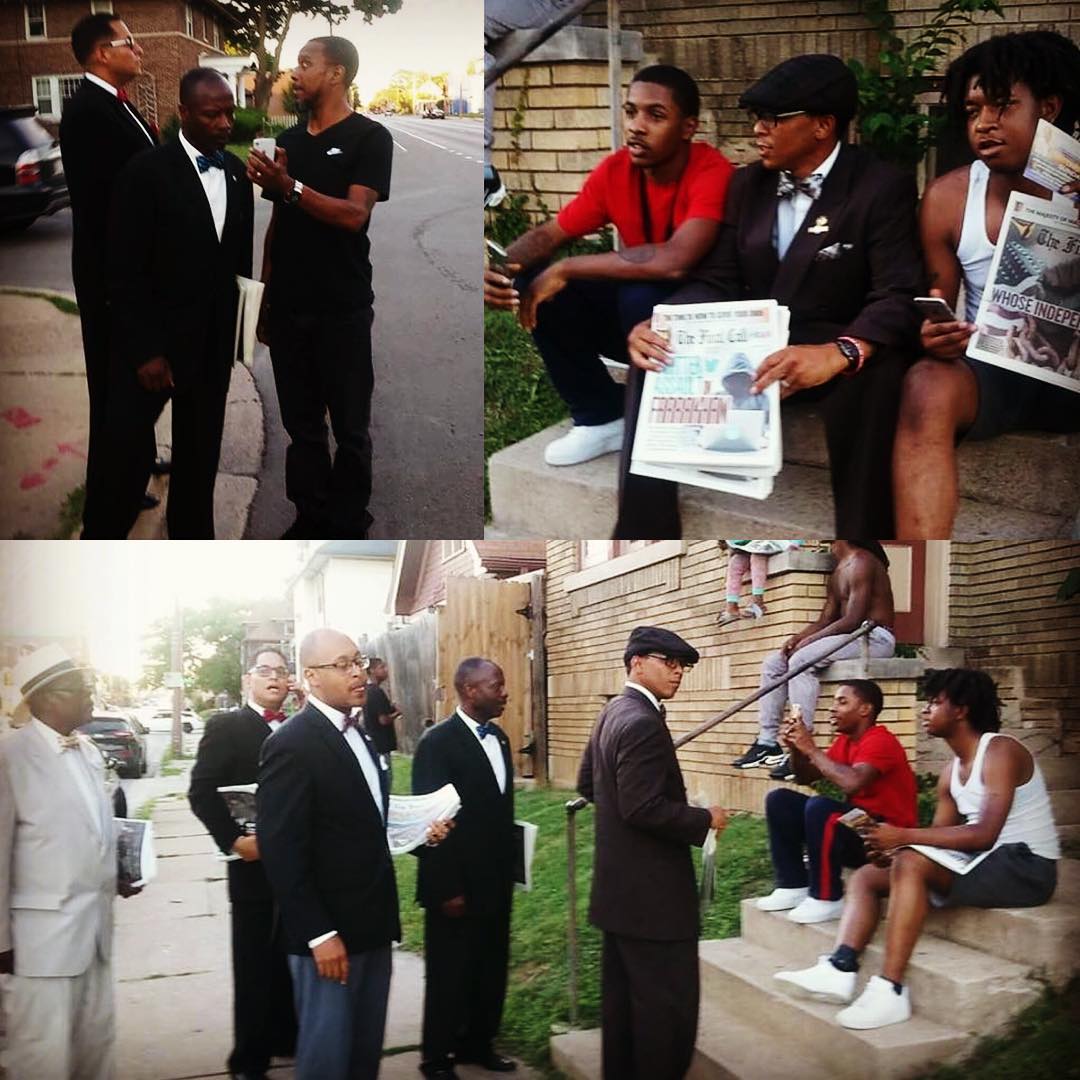

decent places to live. Photos: Final Call Archives

The Pathways Programs focus annually on the top 50 individuals most at-risk of being involved in violence. The Violence Intervention & Prevention Program contracts with three community-based organizations to deploy nearly 40 violence intervention specialists in the D.C. neighborhoods with the highest rates of violence. The Family & Survivor Support Services program provides emergency critical response planning in reaction to all homicides and any shootings suspected of being gang or crew related.

The Zoom meeting was an opportunity for community groups eager and willing to step up and expand their work to reach a unified goal of zero murders in D.C. to share and strategize. They are also looking to create a strategic plan to have a greater impact.

“D.C. has extraordinary talent, in terms of this work,” said Mr. Muhammad. “It also has the ability and the resources. There is this kind of perfect storm of potential, but we’ve got the challenge of coordination. The challenge in some sense of political will, the challenge of focus and strategic planning.”

“The strategic plan needs to be clear. What are you trying to achieve? The biggest challenge I have experienced in the country is aligning your desired outcomes with your programs or your services or your actions. For example, I just happened to be in a city on the east coast and I was talking to a city council member about reducing gun violence over the next 12 months.”

Mr. Muhammad explained that the council member’s idea was to launch a mentoring program for middle schools.

“A mentoring program for middle schools is wonderful. It will never, ever, ever achieve gun violence reduction in the next 12 months,” he said. “So it’s really, understanding, aligning your desired goals with your action programs. What most people who are not deeply involved in this work don’t realize is that in D.C. the average age of a homicide suspect was 29 years old.”

“You’re talking about an older population. Yes. The teenagers make news. It’s in our heads with teenagers and crime. The shootings and the homicides are our young adults, in their twenties,” he said. “What is our plan to engage the 25 year old, who has seven previous arrests, who is an avowed member of his neighborhood crew, who’s not looking for services? He’s not trying to knock down doors to get services, yet he is somebody that you must invest in.”

“He’s someone we need to love on, we need to engage and that can stop you from being seen as a victim or perpetrator of this issue. I would say from the data we have with the District, probably about 75 percent of all shootings, a huge amount of it, is amongst a small population who have very similar risk factors, the violence is very predictable. Therefore it is preventable.”

The recent reports found neighborhoods with high rates of shootings face a mixture of poverty, institutional racism, subpar education, generational trauma, and crime and violence with an overlay of blight, historic under investment, and economic isolation.

An example of community transformation that reduces risk factors for gun violence is Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.

It focuses on creating a physical environment that positively influences human behavior.

Communities across the country that have applied the principles have reported decreases in gun violence, youth homicide, disorderly conduct, and violent crime. Communities have also reported positive impacts on residents’ stress, community pride, and physical health.

Some examples of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design approaches include:

• Repairing abandoned buildings and vacant lots;

• Cleaning and maintaining neighborhood green spaces;

• Upkeeping neighborhood housing.

Focusing efforts to get better results

To reduce gun violence there’s a specific population to focus on, with a specific set of interventions, said Mr. Muhammad.

“We have to develop a plan that’s specific to that. Then what are the metrics that we’re going to collect? What are the objectives we’re trying to achieve? Then let’s manage the hell out of those objectives,” said Mr. Muhammad.

D.C. is one of 25 cities in the National Offices of Violence Prevention Network, a coalition of local governments committed to reimagining what public safety can look like to reduce violence. The network was organized earlier this year by NICJR, Advance Peace and the Center for American Progress.

Among the cities in the Violence Prevention Network are Chicago, Indianapolis, Los Angeles, Louisville, Ky., and Newark, N.J. Each strives to make meaningful investments in violence prevention and intervention strategies that strengthen neighborhood wellbeing while shrinking the footprint of the criminal justice system. In Minneapolis, the Violence Interrupters take to the streets as part of the city’s plan to decrease an ongoing cycle of gun violence at a time when shootings are at a five-year high.

“I’m tired of it,” Yulonda Royster, a Violence Interrupter, told the media as she was starting a recent Friday shift in downtown Minneapolis. “Every day there is some young Black boy being killed being shot. All of this gang violence, it can be prevented.”

Teams are contracted to cover five-hour shifts, six days a week. Outreach workers are paid $30 an hour. The contract began in May and runs through the end of the year.

Last year, Newark decided to divert close to $11.4 million from the city’s $228 million public safety budget toward violence prevention programs after backlash from activists saying defund the police. The city created the Office of Violence Prevention to provide social services.

“This is about the community’s investment in the passions and aspirations of people often overlooked by educational efforts,” Mayor Ras Baraka said in July at the start of the program. “We want to position them to break the generational cycle that leads them to violence, drug use and crime by giving them insight into their innate strengths and abilities to create legal paths to success.”

The network brings together the leaders of local government offices seeking community-driven safety solutions that are overseen by Offices of Violence Prevention.

In the nation’s capital the program is called the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement. It works with groups like the Alliance of Concerned Men started by Tyrone Parker. The 30 year old non-profit provides outreach, intervention, and prevention in working with gang members to help reduce homicide rates. The District of Columbia’s homicide rate was up 14 percent this year as of Oct. 28, with overall crime up by two percent.

“Our mission is to bring conversations to the table that have the capacity of unifying us all in one way. One thing is for sure, a number of us are accustomed to making something out of nothing. This is the way that we’ve been able to do in regard to the streets, in regard to the community, we created ideas where there was no best practices or no evidence based,” said Mr. Parker.

He asked the audience to ponder these questions: “How do we make our community safer and eliminate the homicides … how do we unify? I think to unify our community is to have a real conversation. What are the causes that circumvent us from coming together as a group?”

David Bowers runs nomurdersdc.com, a movement to end murder in the nation’s capital. He starts with the belief that, “One murder is one murder too many.”

When he started work in December 2000, he would walk down the street and ask people what they thought the Black community could do to end murder in D.C.

“It’s been 20 years, 3,796 people have died since the beginning of 2021 until the latest MPD (Metropolitan Police Department) stat, 3,796. That’s more than on 9/11 in a city that was at that time roughly 60 percent Black, now it’s 47 percent Black. Over 90 percent to 95 percent consistently of those folks shot tend to be Black, tend to be male, tend to be from a certain part of town, tend to be from a certain socioeconomic background, not all, but the overwhelming majority,” said Mr. Bowers.

“We have to have an honest conversation about why have we let that happen? We, all of us, mayors, council members, preachers, sorority, fraternity folk, business owners, nonprofits.

Why have we tolerated that?” he asked. “This gathering tonight is part of that movement, the movement to build the will of heart to get there.”

For the near 100 year history of the Nation of Islam, community efforts to promote peace have been ingrained in the group’s work. D.C. was home to the “Dope Busters,” a community patrol that emerged from Muhammad Mosque No. 4 to quell drug traffic and close an open air drug market near the mosque at the behest of tenants in 1989. It was the heyday of the crack cocaine epidemic with its addiction and violence. The work of the Dope Busters, the name affectionately given the men of the Fruit of Islam who engaged in the successful peacemaking, eventually became more formalized with individual Muslims owning security companies that protected residents and public housing communities across the country.

When the Dope Busters began patrolling in 1989, the results were quick. The drug dealers at Mayfair Mansions apartments in northeast D.C., met the discipline, persistence, love and “overwhelming spiritual force” of the Muslims and left. Crime went down, children could come out and play, women breathed a sigh of relief and seniors could walk the neighborhood in peace.

They were widely successful but were attacked by Jewish groups, including the ADL and the American Jewish Committee, and some White members in Congress. The individually owned companies were targeted and subjected to congressional hearings because they were owned by Believers in Islam who followed the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan. Congress forced local public housing authorities to cancel the security contracts by threatening to cut off federal funding to local housing agencies, if the successful Muslim companies were not fired. The contracts were largely canceled by 1996. When the Muslim peacemakers left those neighborhoods, crime, violence and vandalism quickly returned.

Abdul Sharrieff Muhammad, NOI Southern Regional Student Minister, led the Dope Busters and now lives in Atlanta where he commands the 10,000 Fearless, a group that does similar work. There are other 10,000 Fearless groups across the country created by Muslims and allies at the call of Min. Farrakhan. He called for 10,000 Fearless to stand between the guns, drugs and violence plaguing the Black community and make peace.

“The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan asked us to go in our community and make it a decent and safe place to live. We have patrol cars. We patrol the area around with the mosque and the Ark (a building housing community businesses),” said Min. Sharrieff Muhammad.

“We go into the service stations, other people’s businesses, to check on them, let them know who we are. We’re doing this as volunteers right now in the Bluff (neighborhood in Atlanta.) We patrol that area’s homes and will continue until somewhere, somebody at some point will support us. But in the meantime, we are trying to secure the area to make it a decent, and safe place to live.”

He believes lessons learned in Atlanta, where the 10,000 Fearless also feed people, give away clothing, advocate for veterans and others in need and provide other services, can be shared across the country. Nation of Islam members around the country are involved in peace walks, conflict resolution and mediation, community outreach and similar anti-violence work.

Abdul Khadir Muhammad, NOI Mid Atlantic Regional Student Minister based in Washington, D.C., told The Final Call, “We don’t carry guns and we follow our Restrictive Laws. That keeps us in line with the teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. Our example in the community, what we follow and what we stand by, that keeps us in place as an example.”

“The deeper that we go into these areas where the crime and the gun violence is, our presence is seen more. The people get used to seeing us. We get used to them. They’ll find out that our love is much deeper than they thought. They’ll begin to take on a pattern after us, which demonstrates love to each other.”