NNPA Newswire

For decades, hundreds of White-owned newspapers across the country incited the racist terror lynchings and massacres of thousands of Black Americans.

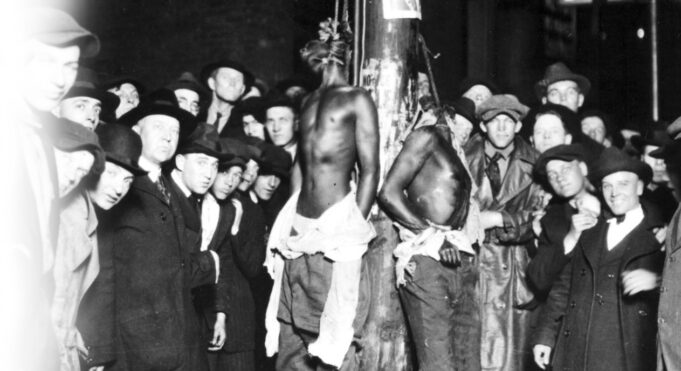

In their headlines, these newspapers often promoted the brutality of White lynch mobs and chronicled the gruesome details of the lynchings. Many White reporters stood on the sidelines of Jim Crow lynchings as Black men, women, teenagers and children were hanged from trees and burned alive. White mobs often posed on courthouse lawns, grinning for photos that ran on front pages of mainstream newspapers.

These racist terror lynchings—defined as extrajudicial killings carried out by lawless mobs intending to terrorize Black communities—evoked horror as victims were often castrated, dismembered, tortured and riddled with bullets before being hanged from trees, light poles and bridges.

Lynchings took different forms. Some Black people were bombed, as four little girls were in a church in Birmingham, Ala. Black men were whipped by mobs to silence them. Emmett Till was kidnapped, tortured, beaten and thrown into the Tallahatchie River with a cotton-gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire.

“Printing Hate,” a yearlong investigation by students working with the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland, examines the scope, depth and breadth of newspaper coverage of hundreds of those public-spectacle lynchings and massacres.

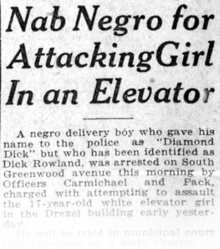

The investigation was inspired by DeNeen L. Brown’s reporting on the Red Summer of 1919 and the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, which was sparked by the sensational coverage of The Tulsa Tribune, specifically a May 31, 1921, front-page story: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator.” The Tulsa Race Massacre was one of the deadliest acts of racist violence against Black people in U.S. history.

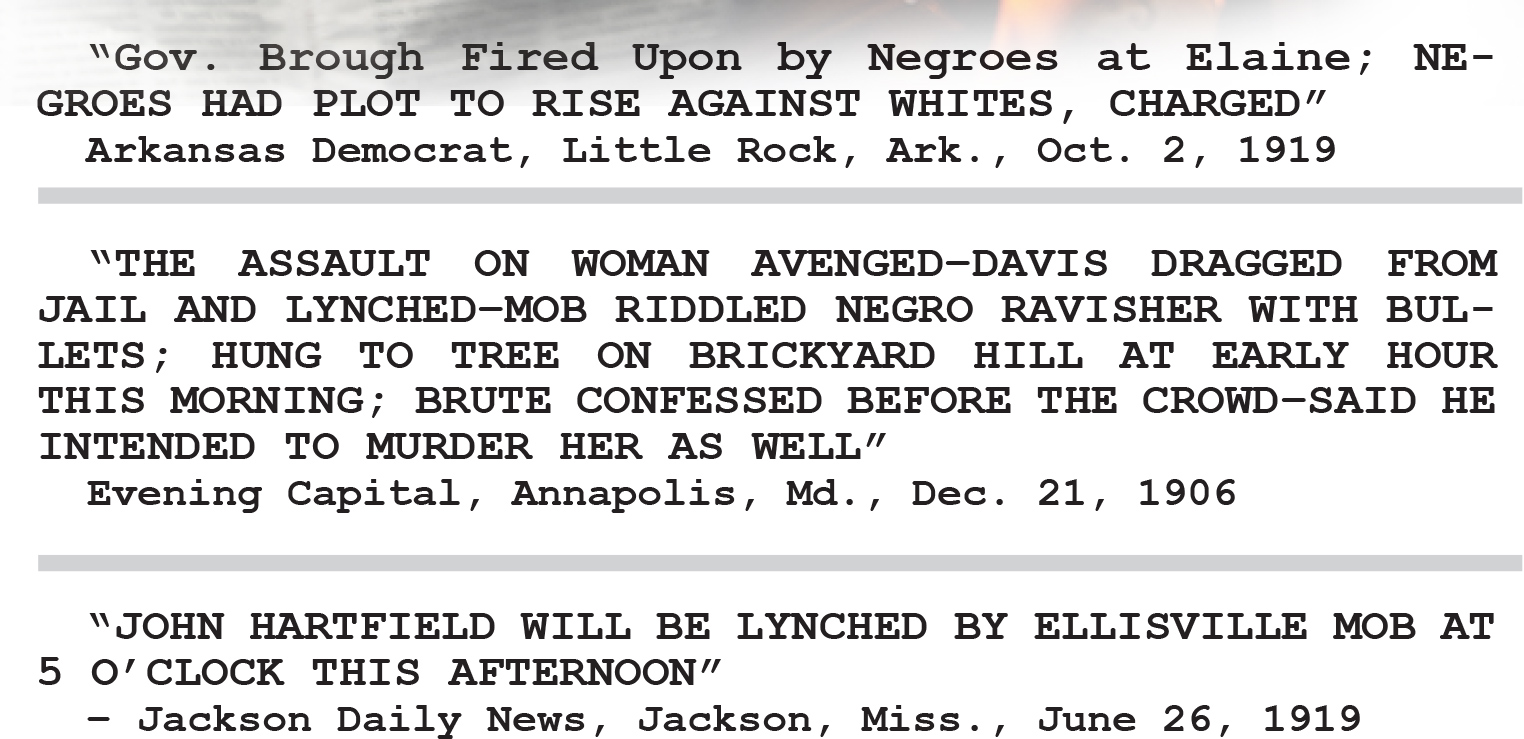

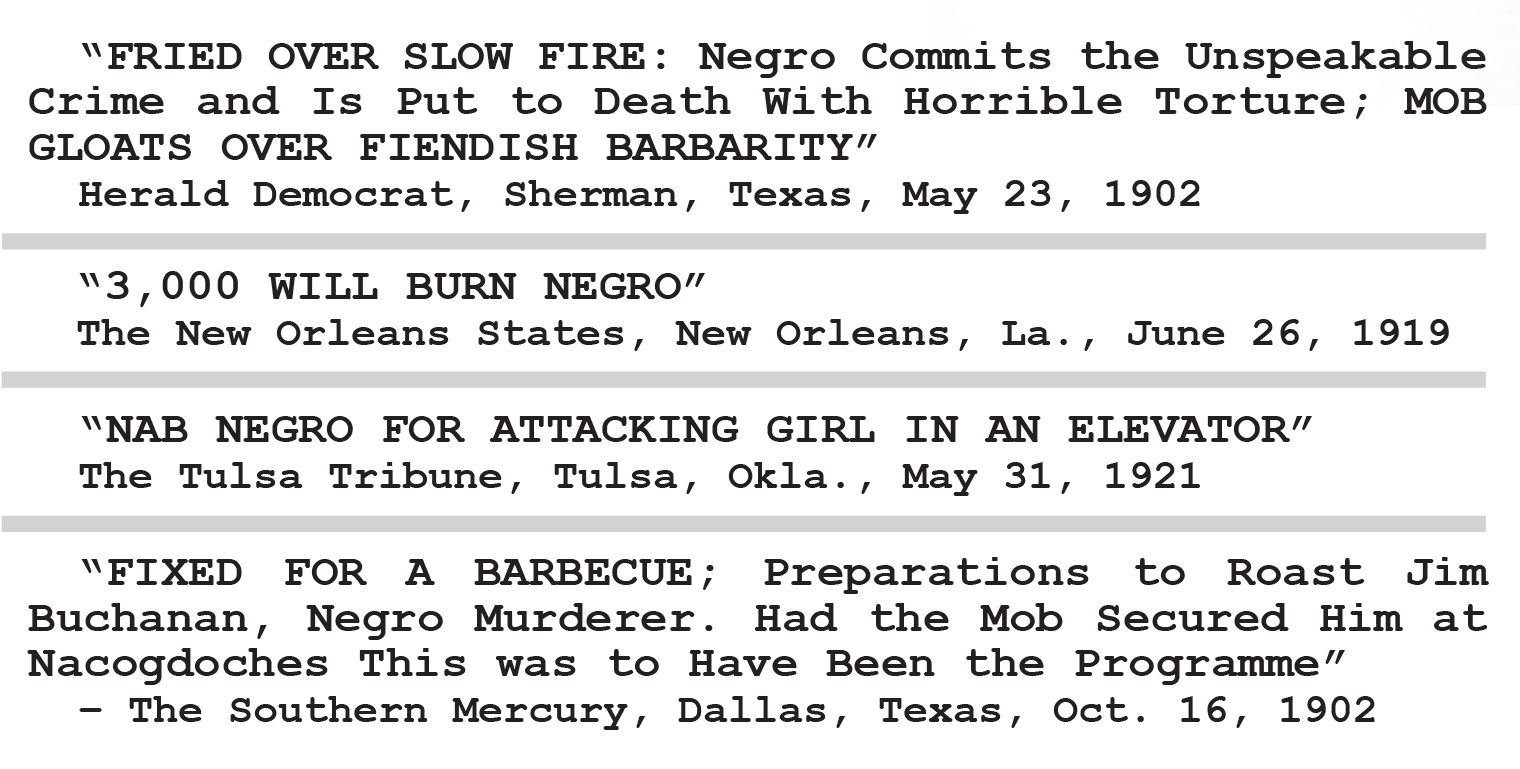

This project investigates the cumulative effect of how newspaper headlines and editorials incited racist terror and falsely accused Black people of crimes. The series uncovers the widespread practice of publishing headlines that accelerated lynchings and massacres. That included newspapers announcing “Negro uprisings,” publishing uncorroborated stories of Black men accused of “assaulting” White women, and printing false allegations of arson and vagrancy—all in an attempt to justify racist terror inflicted on Black people.

Many of the newspapers examined in this project ran racist headlines, calling Black people “brutes,” “fiends” and “bad Negroes.” Newspapers across the South greeted readers with “Hambone’s Meditations,” a racist caricature created by The Commercial Appeal in Memphis, Tennessee. (The Commercial Appeal was owned by Scripps-Howard from 1936 to 2015, when the company spun off its newspapers. The Scripps Howard Foundation supports the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland.)

Some of the newspapers advertised upcoming lynchings, often printing the time, date and place where mobs would gather. Some White reporters watched, took notes and wrote riveting accounts of the barbarity of mobs, documenting the horror of the wounds inflicted, with blow-by-blow descriptions of the attacks, as though they were writing about a sporting event.

Many of those reporters failed to identify White people in the mob. They also failed to hold government officials accountable by asking hard questions of the sheriffs, judges and other local law enforcement officials who stepped aside while White mobs attacked Black people.

This series found that the collective impact of those accounts was devastating. Triggered by front-page headlines, Black people were often dragged from their homes, ridiculed, tormented and whipped with straps so sharp their flesh was shredded.

Sparked by reports, a White mob of more than 2,000 people in Salisbury, Maryland, pulled 23-year-old Matthew Williams from the “Negro ward” of the hospital, on Dec. 4, 1931, threw him out the window, stabbed him with an ice pick, and dragged him to the courthouse lawn. Before dousing him with gasoline, they cut off his fingers and toes, then drove to the Black side of town, where they tossed his body parts onto porches of Black people, while shouting for them to make “N—– sandwiches.”

The project reveals how the scope of the news of the day for some Americans was often ghastly, shaping the American landscape and psyche. The front pages included pictures of people being killed in the most horrible ways. The lynchings were covered as an everyday occurrence, often reported side by side with who graduated from college that day and stock prices. A reader could open the newspaper in the morning and casually scan the headlines reporting baseball scores, finalists in beauty contests, reports on tariff negotiations and a news story advocating lynchings.

The fact that lynchings took place is generally known, and the fact that some newspapers incited lynchings is generally known. But the Howard Center’s reporting shows how widespread this incendiary coverage was. It was not a question of this coverage just happening in places like Wilmington, North Carolina; Montgomery, Alabama; or Atlanta, but it happened in small towns across America.

Not all White-owned newspapers were guilty, and there were degrees of guilt. In some instances, editors looked the other way. In other instances, they not only covered the fire; they lit the fuse.

“Printing Hate” examines White-owned newspaper coverage of lynchings and massacres from the end of the Civil War in 1865 to the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

During those 100 years, thousands of Black people were murdered in massacres and lynchings.

In that same period, nearly 5,000 racial terror lynchings of Black people occurred, according to a Howard Center analysis of the Beck-Tolnay inventory of Southern Lynch Victims and the Seguin-Rigby National Data Set of Lynchings in the United States.

Lynchings were often public-spectacle executions “carried out by lawless mobs, though police officers did participate, under the pretext of justice,” according to the NAACP, which in 1919 published “Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1919,” to promote awareness of the scope of lynching.

A multifaceted investigation

The series of stories in “Printing Hate” resulted from a multifaceted investigation by 58 student journalists from the University of Maryland, the University of Arkansas and five historically Black colleges and universities: Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, Morgan State University and North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University.

The students spent months examining hundreds of newspapers to detail the complicity of many White newspaper owners, publishers and journalists who used headlines, articles and editorials to incite racist mob violence and terror, in the form of lynchings, massacres and pogroms.

In the course of this investigation, student journalists examined hundreds of headlines and news reports that were collected in an original database designed by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism.

“We found lots of examples of sensationalized coverage and trumped-up charges,” said Sean Mussenden, data editor at the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism, who worked with student journalists who built a database to allow many papers to examine their past lynching coverage. “As someone who has worked in the industry for a long time, I understood newspapers to be imperfect institutions that nonetheless served as guardians of truth who righted wrongs and exposed corrupt officials. I was shocked by the role so many papers played in promoting a culture of racial terror.”

The students were not the first to uncover the White newspaper coverage, which was often countered by the Black press. However, they were able to investigate as reporters of a new generation bringing a 21st-century perspective to the project.

This investigation of newspaper coverage of lynchings comes at a time of “racial reckoning” in newsrooms. The stories dive into the country’s racist history, at a time when states are passing laws to prevent that truth from being told, under the guise of banning the teaching of critical race theory—designed to be taught in law schools.

The series begins at a time when several major newspapers have issued statements, acknowledging and apologizing for racist coverage. “Printing Hate” attempts to add to this discourse by providing a more comprehensive review of that racist historical newspaper coverage that incited the deaths of thousands of Black people.

Rollout

“Printing Hate,” initially published in late October, will roll out over the coming three months, publishing to the University of Maryland’s Capital News Service and Howard Center website. It is also scheduled to appear on the National Association of Black Journalists’ website.

Over the course of these months, the project seeks to tell the story of the Black Americans who were betrayed by American newspapers, whose job should have been to report the facts and circumstances fairly and accurately.

Newsrooms

“Printing Hate” contains interviews with current newspaper editors who have issued apologies and with those who have not. The project examines how the U.S. government failed to enact anti-lynching legislation to prevent the murder of Black people.

Readers will find interviews with descendants of lynching victims, including an account of the lynching of William Henderson Foote, who was killed by a mob in Yazoo City, Miss., in 1883. He was the first Black federal officer to die in the line of duty, “defending the rule of law in protection of a citizen’s basic civil right,” the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives determined.

The series showcases compelling narratives of those impacted by newspaper accounts, including the 1908 case of Annie Walker, who begged “night riders” for mercy before she was killed, according to a report in the Public Ledger newspaper in Kentucky.

The project features a timeline, written by a visiting professional, which connects the dots between racial terror massacres and lynchings, and failed attempts by Congress to pass anti-lynching legislation.

“Printing Hate” includes a story explaining how White-owned newspapers conspired to destroy a political party in Danville, Virginia, coverage of the lynching of Sank Majors and the inhumanity of Waco, Texas, where massive public lynchings of Black men were nurtured by the city’s newspapers. The project includes a story about The Columbus Dispatch, which condoned the lynching of John Gibson, published under the headline, “NEGRO FIEND MEETS HIS FATE.”

The Atlanta Journal wrote an editorial in 1906 in support of “the legal disenfranchisement of 223,000 male negroes of voting age in Georgia.” The Journal claimed to support the disenfranchisement of Black men because “we are the superior race and do not intend to be ruled by our semi barbaric inferiors.”

The “Printing Hate” package of stories sweeps West to the blood-soaked cotton fields of Elaine, Arkansas, where newspapers inaccurately reported in 1919 that Black people in Elaine were engaged in an “uprising” against White people. Those headlines were essentially dog-whistle calls to White people in Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee and surrounding states to descend on Elaine and literally hunt and kill Black people.

In “Printing Hate,” students write how the press covered jazz great Billie Holiday when she sang about “Strange Fruit”; how lynching photos and postcards were used by the media to foment terror; and about the courage of many journalists in the Black press who—often despite threats to their lives—pursued the truth about lynchings. This includes fearless anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett; Walter White, who investigated lynchings for the NAACP; Robert S.

Abbott, founder of The Chicago Defender, whose masthead promised “We Print THE TRUTH No Matter Whom IT HURTS;” Simeon S. Booker Jr., the first Black reporter for The Washington Post, and an award-winning journalist who covered the civil rights movement for Jet and Ebony magazines; Moses Newson, a reporter for the Tri-State Defender in Memphis and the Baltimore Afro-American, who covered the 1955 trial of the White men who lynched Emmett Till in Mississippi.

Roscoe Dunjee, the founder and publisher of The Black Dispatch newspaper in Oklahoma City and a fearless crusader for justice, wrote in a 1919 editorial that White editors across the country—including at The New York Times and The Washington Post—should cease printing inflammatory headlines and false reports about Black people, which Mr. Dunjee wrote incited racist violence.

As evidence, he cited a July 1919 Washington Post headline that provided the precise time, date and location where White mobs would “mobilize” near the White House to continue attacks on Black people during the D.C. Massacre of 1919, which left as many as 39 people dead.

“As long as editors encourage lawlessness as cynically as the editor of The Washington Post, there can be no hope of averting mob violence anywhere,” Mr. Dunjee said.

C.R. Gibbs, a historian and author of “Black, Copper, & Bright: The District of Columbia’s Black Civil War Regiment,” said newspapers often amplified community attitudes about race and racism.

“They provided the oil to throw on the fire of racial intolerance,” Gibbs said. “They essentially abandoned the cardinal rule of the press to report fairly and accurately. When we look at the vitriol splashed across newspapers across the country, when it came to race, they should still be liable for some sort of justice. These headlines had the real effect of taking people’s lives, of making people’s situations that much worse time and time again. They were not fighters for truth and justice. They were propagators of violence, oppression and bloodshed.”

Victoria A. Ifatusin, a graduate student at the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism, said working on the project was a profound experience.

“We talk about social injustices today and how Black people were treated back then quite often,” Ms. Ifatusin said. “But I don’t think that people, including me before this project, really understood how Black people were horrifically mistreated, to the point that their lives were taken just for their skin color. And newspapers, a medium of truth, aided in that mistreatment.”

Written by DeNeen L. Brown, of the Howard Center For Investigative Journalism. Vanessa Sanchez and Brittany Gaddy contributed to this report. Ms. Brown is also an associate professor of journalism at the University of Maryland. This article was distributed by the NNPA Newswire.