WASHINGTON—To say that Roy Lewis is a legendary photographer is an understatement. He is a cinematographer on an Oscar-awarded film, a photographic griot, a visual historian. Through his lenses, he has documented 60 years of Black history.

“Roy Lewis’s primary concern has been to be a real organic part of local, national, and global Black community,” James Early, Assistant Secretary of Education and Public Service Emeritus, at the Smithsonian Institution, said in an interview. “And to be a participant, but also to be a mind’s eye of reflecting the most resonant, expressive dimensions of our lives.”

That means he has been a visual griot, a visual historian for much of the 20th Century and for the entirety of the 21st Century. He was born in Sibley, Mississippi, south of Natchez in 1937. His professional career began with a 1964 photograph published in Jet magazine of the immortal jazz pianist Thelonious Monk. Notably, his work has remained rooted almost exclusively in the Black Press.

“Whether it be social justice and our revolutionary struggles. Whether it be cultural expressions in music, song, dance, the dignified imagery of ordinary Black people and their profundity. This has been his primary concern,” Mr. Early continued. “Contrasted with, what we normally think about as an excellent and notable photojournalist, photo artist, photo documentarian, as being someone who had been raised as her or his own profile, in order to be able to bring that mind’s eye reflection to a broader public.”

So, if we were to now academically define Black “legendary photographer” with a single picture, it would certainly depict Roy Lewis. If Henrik Ibsen’s oft repeated adage from the 19th Century, that “a picture is worth a thousand words” is true, then Mr. Lewis’s portfolio must be worth one billion words because during the breadth of his career, Roy Lewis has certainly recorded at least one million pictures.

His career began in 1956 when he joined the migration, traveling up the Mississippi River from Natchez, to Chicago. When he got to “The Windy City,” he invoked a greeting from his godmother, who had been a teacher of John H. Johnson, the founder of Johnson Publishing Co., and publisher of Ebony, Jet, and Negro Digest magazines.

A young lady knocked on Mr. Johnson’s door,” Mr. Lewis recalled in an interview, “and I told him, my godmother said hello and he said, ‘Oh yeah, my godmother.’ So, the young lady then told him I was looking for a job and the next week I was working there in the subscription department.

He was really, now “enrolled” in the “Johnson Publishing University,” as he calls it. There, as an apprentice to iconic photographers Isaac Sutton, Moneta Sleet, Herbert Nipson, Lacey Crawford and Ted Williams, and under the tutelage of Jet editor Robert Johnson, Mr. Lewis improved his craft and even branched into filmmaking.

One thing which has made his work stand out in the pages of history, is his presence at historic places when monumental events took place. “A lot of my work has been trips and traveling and conferences and going here, going there,” he said. “My first endeavor into photography (occurred with) the editor of the newspaper, I worked with (in Natchez), The City Bulletin,” Mr. Lewis said. “Bill Williams, he had a camera, he was the editor. So that started me.”

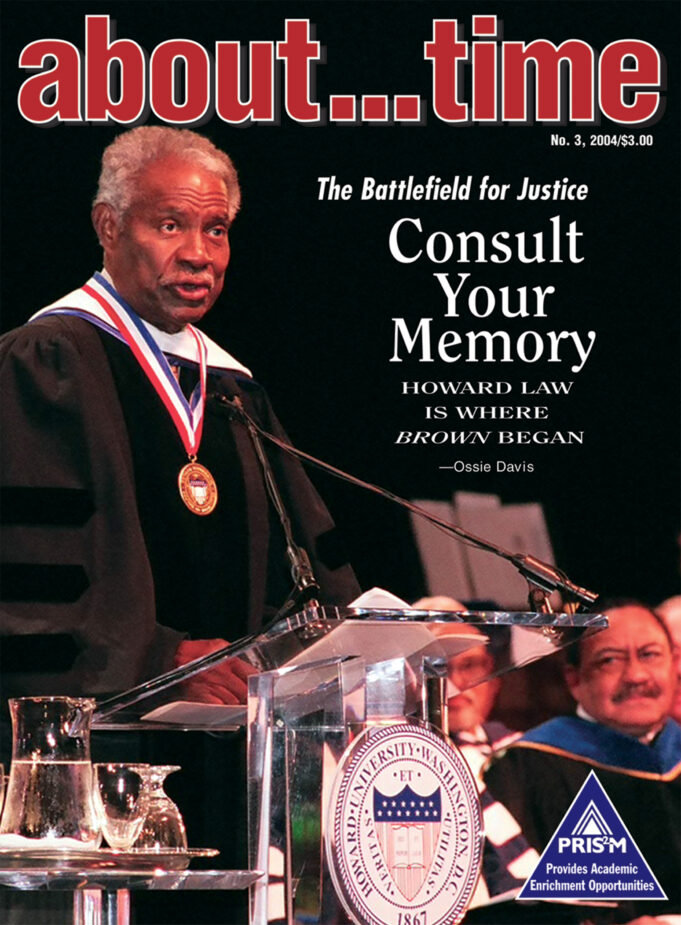

“Roy is a documentary photographer. So, when he covers something, he covers it from beginning to end,” said Caroline Blount, editor of About Time, a magazine out of Rochester, New York which has published as many as a dozen photos by Mr. Lewis on its covers.

“And the beautiful part about it is that when he shares those images with you, then that gives you an opportunity to look into those images and look for something that’s really special. So, for instance, when he covered The Million Man March, he had some dynamite things in there,” Ms. Blount continued. She is not alone in appreciation of his enormous body of work.

“I saw some of the extremely important documentary films he completed on a national Black political convention held in the city of Gary. I think it was only the second such convention in over 100 years,” Ozier Muhammad, grandson of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, told this writer via email.

“I also saw a wonderful documentary that he did on the poet and Pulitzer Prize winner Gwendolyn Brooks,” said Mr. Muhammad, himself a Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times photographer. Mr. Lewis is especially fond of his images of Ms. Brooks, and Howard University poet Sterling Brown.

“I simply remember anything that had to do with the Black Arts movement, Black culture or Black political empowerment, Roy was usually a part of it, capturing it with his camera— mostly, a movie camera,” Mr. Muhammad recalled.

“He also has a way of tapping in and latching himself to different people to do a historical perspective on those people. So, for example, Dorothy Height, Sterling Brown. You name it, he’s done it. Martin Luther King for that matter, back in that time frame,” Ms. Blount said.

Mr. Lewis was prominently associated with the original Chicago “Wall of Respect” mural, and the national Wall of Respect movement. His career literally spanned the Black Power movement beginning in early 1960s. One of his favorite photographic subjects then, was Ms. Brooks.

“That picture of Gwendolyn Brooks that a lot of people have seen, her with the Afro, when she first converted to the Afro. A Black woman group in Chicago commissioned me to do that portrait. And so, I did it and it became, well (known). She bought a lot of images from me, which are now at the University of Illinois, in a collection.”

At the same time, he was finding more and more work as a cinematographer on a number of highly regarded projects. “The film that we did in 1970, with Muhammad Speaks (newspaper), working with St. Claire (Bourne, Wali Sidique),” is one project in which he still takes pride, he said.

“I did a couple of films with St Claire. And then in ‘70, we did ‘The Nation of Common Sense.’” That was a WNET/PBS program for the series “Black Journal,” focusing on the Nation of Islam and its goals of total economic self-sufficiency and racial separation. Various NOI enterprises are shown, such as the Muhammad Speaks newspaper and Shabazz Bakery, and a number of prominent NOI members, including the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, are interviewed.

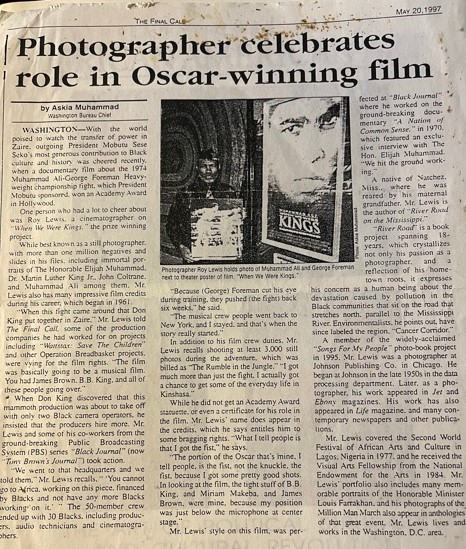

He also worked on “Fight of the Champions,” in 1974—the original footage of what became: “When We Were Kings,” a film about the legendary “Rumble in the Jungle,” when Muhammad Ali successfully regained the Heavyweight Boxing Championship from George Foreman. It featured James Brown, B.B. King, and Don King, in the lead-up to the fight and the accompanying Zaire 74 music festival, along with interviews of Norman Mailer, George Plimpton, and Spike Lee. That movie won a coveted Oscar, from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1996.

Today, Mr. Lewis’s traveling exhibit of some of his photos, is now on display in Atlanta. It is titled “Roy Lewis, Everywhere,” and it would seem that he has taken pictures of almost all of the major figures in 20th Century Black history—the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Coltrane, Dr. Dorothy Height, Muhammad Ali, Minister Louis Farrakhan, among them—everywhere, all over this country and in many corners of the globe.

In late October, the 84-year-old Mr. Lewis was named the “Best Photographer Over 83,” by writer Sidney Thomas in the “Best of DC” issue of the Washington City Paper. Best photographer, of any age group, indeed.

“I also remember his very positive spirit, his affability, comfort in conversing on any topic that had to do with Black art and culture and his seemingly endless reservoir of energy,” Ozier Muhammad recalled.

Looking forward, Mr. Lewis said, “I’m really interested in finishing up some of these book projects. I mean, (take) the exhibit down off the wall and put it into the book, ‘Everywhere with Roy Lewis.’ And then there’s a book on River Road, which is about the environment that I worked hard a long time. I want to finish up these books. I want to put some protections around them.

“The thing is I own my work and you know, there’s a difference. And my purpose during that period was in fact to cover our history and now (it) is to continue to own our history and keep it in Black hands.

“I’m interested in now putting some protection around my collection, around my archives. And that to me really is important and my family benefited from all working troubles that I went through and the sacrifices,” he said.