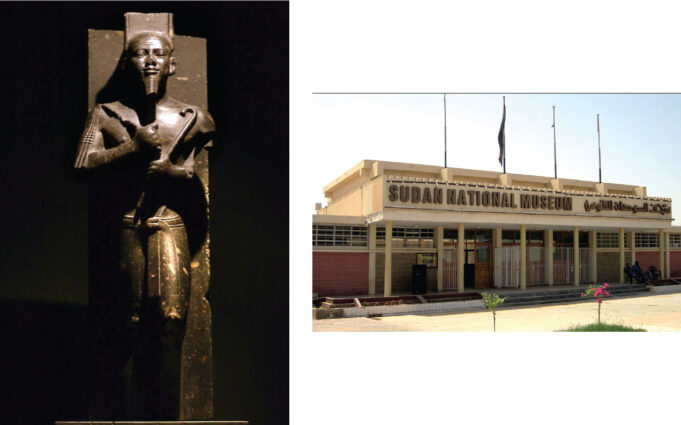

KHARTOUM, Sudan—My first response after touring the Sudan National Museum in Khartoum was that it was a sin and a shame that a country as rich in history as Sudan has not invested heavily in preserving its history.

I told my fellow visitor to the museum, the son of the late Sheikh Hassan Turabi, Sudan’s former attorney general, former speaker of the House and known for his Islamic scholarship and practical application of its precepts, “What an inspiration to Sudan’s majority youth population it would be if its Black African heritage, its Black history, its Nubian history, that in many cases rivals Egypt, was on everyone’s lips.”

In response, Siddiq Turabi noted what a source of revenue it would bring if the Sudanese government invested in its antiquities and tourism trade and paving its potholed roads, instead of catering to European and American neocolonial interests.

During the age of imperialism, European powers scrambled to divvy up the continent. However, in Sudan a Muslim religious figure known as “the Mahdi,” Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, led a successful Jihad (holy war) that for a time drove out the British and the Egyptian colonizers. After four years of struggle, the Mahdi and his forces overthrew the Turks, Egyptians and British administration and established their own “Islamic and national” government with its capital in Omdurman.

So why isn’t there a modern film focusing on this 19th century revolutionary, and his successful battles waged against his country’s Egyptian and British colonizers?

The JSTOR (a digital library) in collaboration with the Cambridge University Press, in a study titled, “The Sudanese Mahdi: frontier fundamentalist,” opens with the some contrived, some authentic depictions of the Mahdi, “as a villain, as a hero, as an anti-imperialist revolutionary.” One thing for sure, the context of his battles was anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, and the cause was the creation and preservation of an Islamic state.

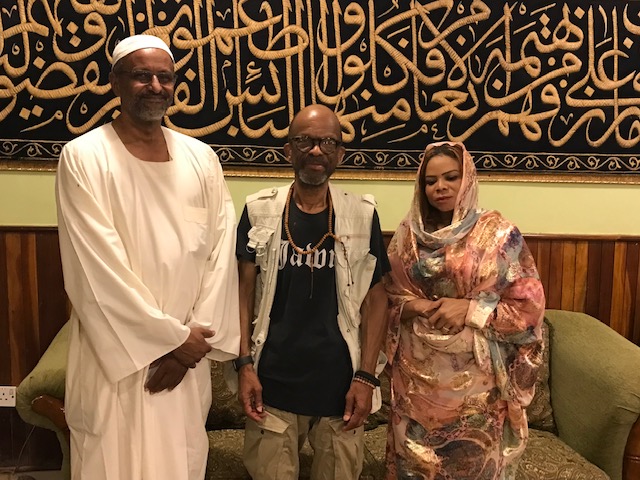

Siddiq Turabi’s mother is a fourth-generation descendant of the Mahdi family. During an interview in his home in Khartoum he noted, “Most of the Mahdi’s history is written as military history of Sudan.” Turabi, who graduated from Indiana University, added, “Unfortunately not so many philosophical, cultural and economic, and social studies on ‘the Mahdi’ are yet published. Maybe they are done, but as of yet, not published. But the most published are in the military books.”

During a similar discussion at Sheikh Hassan Turabi’s museum-like home that included members of the Turabi family, the conversation went to whatever happened to actor Will Smith’s film about historical Sudan that included its Nubian ruler of Kush, Taharqa? According to The Guardian, Randall Wallace, “who penned Braveheart for Mel Gibson, had signed up to write the screenplay for The Last Pharaoh, about the Sudanese-born king and military genius who battled Assyrian insurgents seven centuries before the time of Jesus Christ.”

According to Variety, “Smith (in 2008) personally asked Wallace to work on the story, which will centre on the pharaoh’s battles with the Assyrian leader Esarhaddon, which began in 677 B.C. The role of Taharqa is reportedly one Smith has long hankered after.”

New York’s Jewish Forward in a piece titled: “Will Smith Lesson for Jerusalem,” gives the actor credit for taking on a historical project where he as a Nubian general later to become the ruler of the region saves Jerusalem, which some say may have changed the course of history. Note: The Middle East some historians say was always a part of Africa. It only became divided in 1869 with the creation of the 120.1 mile Suez Canal, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea.

“The figure of Taharqa, who was born in what is today Sudan, is linked to a pivotal historical event that is described in the Bible: the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem in 701 BCE. Hezekiah, the king of Judah, had little chance of surviving that onslaught by one of the greatest military powers on earth; only two decades before, the Assyrians had conquered the neighboring kingdom of Israel and deported many of its citizens,” reported the Forward.

“Unfortunately, the young people (of today) don’t know much about this history,” noted Siddiq Turabi. He described himself as “a student interested in history in elementary, middle and high school. In today’s school there is not that much historical content as in past. I personally received more history because of family reasons.” He said his father, grandfather and great-grandfather were all towering historical figures, including his mother, so history was important to appreciating who he was and the great potential he inherited from his ancestors.

Much of the historical data concerning Sudan always intersects with Egypt as though Sudan doesn’t have independent history. Some clarity came from Nubian filmmaker Hafsa Amberkab and her reclaiming the power of the narrative by connecting younger generations to their language and culture that was lost in their drowned ancestral land.

A piece appearing on the BBC titled “The Women Reviving Egypt’s Nubian Heritage” highlights how Nubian heritage is also Sudanese in its origin and Kushite at the root.

“Indigenous to southern Egypt and northern Sudan, Nubians of the eastern Sahara have been closely connected to Egypt for millennia. The Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, for instance, consisted of Nubian pharaohs from the Kingdom of Kush who ruled Ancient Egypt in the 7th Century BCE. Though the foundation of modern Egypt included the area known as Lower Nubia, the ethno-linguistic group, which now mainly lives north of Lake Nasser (called Lake Nubia south of the Sudanese border), is historically and culturally distinct from other communities in Egypt,” according to filmmaker Amberkab.

According to “The Sudanese Mahdi: frontier fundamentalist” study and Siddiq Turabi interview, there should be continuing interest in the Mahdi of the Sudan in terms of where to place his contributions in the fundamentalist part of the (global) Islamic experience. And, to take it one step further, the belief in monotheism or in One God claimed by Akhenaten stands out in terms of his relationship with the Creator.

Why didn’t the Will Smith film on the savior of Jerusalem make the cut, or the production of a modern-day film about the Sudanese Mahdi? Instead, we have the 1966 film “Khartoum” staring Charlton Heston as a so-called devout colonizing Christian defending Khartoum against the Sudanese born Mahdi, played by Laurence Olivier.

Why not conflate Sudan’s entire history including Dr. Hassan Turabi, and his historical work on the Islamic movement in Sudan and the country’s important contribution to history?

Follow @jehronmuhammad on Twitter.