Former Boston Police Officer Brenda James has been fighting alone for over a decade.

She began her career in the early 1990s after a tumultuous time in the city of Boston, where racism is known to be pervasive, according to her written interview with The Final Call. Ms. James was entrusted to be one of the faces of community policing and then became a juvenile officer. She would mentor young adults and children, and she was a veteran officer in good standing and a clean record. But she was a Black woman in a White male-dominated field.

She described her career as “being fraught with retaliation, sexism, discrimination, hostility.” A series of experiences altered the trajectory of her life. While Ms. James was on injured leave, her commanding officer deviated from protocol, arbitrarily changed her duty work status to Absent Without Leave (AWOL) and unlawfully tampered with her wages, leaving her with a zero-dollar paycheck for over one month. But she followed protocol and returned to work.

Then on June 8, 2012, after six months of working without any incidents, her commanding officer came onto her shift at 1:00 a.m., knowing that her union representative was off, and attempted to have a two-way dialogue with her about his actions, according to Ms. James.

Without provocation or a warning, her commander wrangled her loaded firearm out of her holster and suspended her for the erroneous duty work status that was later expunged from her record. Her suspension was also subsequently rescinded. Ms. James was immediately labeled a liar after filing a required incident report, which her own department approved and categorized as a sexual assault incident. A series of retaliatory actions ensued.

Ms. James has been “voiceless, not treated fairly and fighting for justice for over a decade.” Her current union president stated that prior union presidents (both accused of felonies) said that the department did not want her back on the job. Numerous union attorneys have been paid to give her adequate legal representation. However, important information has been left out of legal arguments, a plethora of other roadblocks and there has never been an attempt to resolve the matter, Ms. James pointed out.

“This matter is a microcosm of a larger issue that has existed long before I became a Black Female Officer in the City of Boston,” she wrote to The Final Call. “The atrocity here is that this matter has nothing to do with my job performance and work record, which has been demonstrative of the commitment I made under oath in 1994, to engage positively with my community and make a difference. This ongoing matter needs to be addressed with transparency, impartiality and non-bias, to not only make me whole but also assure the public trust that is continuously being promised,” she added.

Ms. James is one of several Black women officers all over the country who are standing up against racism and sexism in their departments and are longing for change.

Discrimination in D.C.

Sergeant Tamika Hampton was a 21-year-old recent graduate from the police academy when a Black male sergeant wanted to date her. She rebuffed his advances, going so far as to tell him she was engaged, even though she wasn’t.

“He just didn’t care. So, he ended up telling me he’ll make my career miserable,” she told The Final Call. He made good on his word by sending her to a high-crime area without a partner.

Sgt. Hampton is one of 10 Black women officers suing the Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Police Department, charging they experienced racial discrimination and sexual harassment. Other parts of the suit include Assistant Chief Chanel Dickerson; 2019 “Officer of the Year” Tiara Brown, who has resigned; Officers Sinobia Brinkley; Kia Mitchell; Regenna Grier and Tabatha Knight, all of whom say they were forced out of the department; and officers Karen Carr and Leslie Clark and Lieutenant LaShaun Lockerman, all of whom are still on the force.

Sgt. Hampton’s last experience with discrimination took place in September, almost 18 years later after she first joined the force. A shooting occurred, and she rode to the scene with a White male sergeant. While at the scene, the sergeants wouldn’t talk to her, refused to listen to her, and one ended up pulling his gun out in front of an upset crowd of Black people. Sgt. Hampton was successful in deescalating the situation, but soon after, her partner left her on the scene.

“That has never happened in my 18-year career, never. You never ever leave the person that you ride in with unless you go to that person and you have something specific that you need to do and you talk to that person and say, ‘Hey, I’m going around the corner, I’m going here. Are you going with me? Are you going to catch a ride?’ Something like that, but you never ever just leave your partner, and that’s what happened to me,” she said.

The male sergeant ended up returning, but both he and her lieutenant left soon after.

“I had to get a ride back with an officer. That showed everyone on that scene that he basically disrespected me. He left me, which was a way to embarrass me, to show people that they don’t have to respect me,” Sgt. Hampton said.

When she got back to the office, it took another sergeant calling her partner to get him to return to the office. Her belongings were still in his car. When he returned, she said he didn’t acknowledge her. He stood right beside her and conversed with another sergeant. When asking about her bag, she described that he looked at her with disgust.

“He didn’t even have any remorse for what he had done. He didn’t even care, and he was being extremely condescending to come back in the office, stand next to me and then talk to someone else, and didn’t even acknowledge what had just happened,” she said.

Sgt. Hampton is looking for change in the department and a mandate to stop systemic racism and misogynistic behavior that Black, female cops often endure.

“I think something important to point out is that Tamika pointed out to her leadership that this had taken place and in a normal circumstance, normally, the leadership would have reprimanded that sergeant, would have made it clear to the team that leaving your partner is unacceptable and would have handled the situation,” said the case’s lead attorney, Pam Keith, to The Final Call.

“Instead, they just acted like it was no big deal. Because when it happens to a Black female police officer, then I guess it’s not a big deal.”

Atty. Keith said all 10 Black women officers are alleging the same thing, that the culture in the police department is discriminatory to Black women and disproportionately affects them.

There are four components of police culture that they are trying to get changed in the class-action lawsuit: the culture of bullying, disrespect, sexism, racism and disrespectful comments; the abuse of power culture; the lack of investigation when Black women file complaints; and the retaliation that Black women face when they do complain, such as discipline, terrible assignments, being ignored and false allegations.

Atty. Keith said the lawsuit has been filed and is currently in federal court and that the city has a month and a half to respond to the lawsuit. The women are asking for two things: compensation and for a judge to appoint a neutral third person to oversee the equal employment opportunity department and the personnel and training policies of the police department. Right now, the equal employment opportunity department is under the chain of command of the chief.

Racism, sexism from Chicago to San Francisco

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, in 2016, only three percent of full-time sworn police officers were Black women. Many of the Black women officers interviewed by The Final Call expressed it took some time for them to consider even joining the force.

Carmella Means had negative experiences with police, and Yulanda Williams attempted to avoid law enforcement as much as possible. Fast forward and it has been 26 years since Ms. Means has been with the Chicago Police Department and 31 years since Ms. Williams has been with the San Francisco department.

“I ended up getting on the job, but me as a Black woman being on the police department, I always knew that first and foremost, I am a Black woman, and my occupation happens to be a police officer,” Officer Means said.

She grew up on the South Side of Chicago and has always believed in fair and constitutional policing. When protests started in the summer of 2020 over the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis cop, a few younger officers with the Chicago police kneeled in solidarity with protesters. Off. Means thought it was a good thing.

“I thought that they were pretty much telling the community that we hear you and we’re gonna kneel in solidarity with you, because we all want to achieve the same thing,” she said. “We want a better police department. We want to fight against police abuse and fight against systemic racism that is in our criminal justice system.”

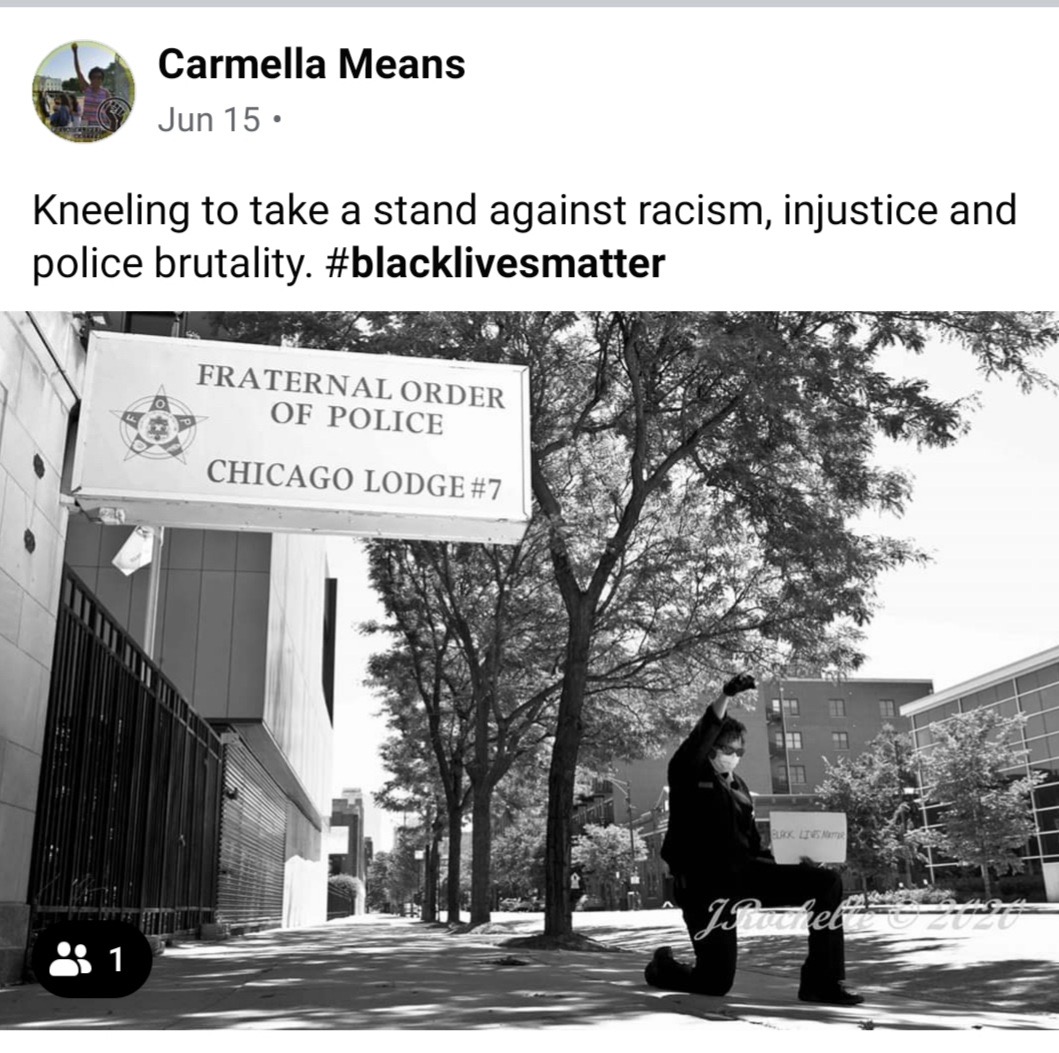

But John Catanzara, president of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), who is White, condemned their actions. After she heard his statement, Ms. Means decided to kneel in front of the FOP while in uniform to show her support for Black Lives Matter. She took a picture of her kneeling and posted it to her Facebook account.

Shortly after, she received charges from the FOP, stating that she violated the union’s constitution and bylaws and violated the spirit of fraternalism. She was suspended for six months, from March 1 to Sept. 1. She tried to appeal the charges at the state level, but she said the president of the Illinois FOP, Chris Southwood, is friends with John Catanzara. She also reached out to the national FOP president, Patrick Yoes.

Even though her suspension is over, she is still fighting the charges. “I’m going to continue to fight on. I’m going to continue to speak out on it. I’m going to call out to Patrick Yoes of the national FOP that he needs to address the actions of his subordinate lodges and how they’re treating their minority officers,” she said.

On the West Coast in San Francisco, Yulanda Williams is the president of the Officers for Justice, Peace Officers Association, made up of Black officers. She said as a Black woman, law enforcement hasn’t been easy.

“Oftentimes, we stand alone, and we have to advocate for ourselves and hope that we can still stay employed and that we won’t be victims of retaliation. So, law enforcement is not easy for a Black female. It is something that you have to be prepared for, and you have to be, as I call it, armed with the full armor of God,” she said.

In 2015, FBI investigated officers in her department and discovered racist, sexist and homophobic text messaging.

“In some of their text messages, they referred to me as a ‘nigger bitch,’” Ms. Williams said.

She said prior to that incident, she didn’t think there was a difference between anyone who wore the blue uniform, and she described herself as being naive.

“I thought we were truly one happy family of blue, where you had all of these people who would always be looking out for you. I just really believed that in the heart of hearts,” she said.

“It was absolutely shocking for me when I discovered something other than that, and especially when one of the officers who was involved in the texting had actually been in a training course with me and had told me how much he had respected me and cared for me and what a great friend I was to him,” she said.

That was her awakening. Now, the police department is working to implement 272 reform recommendations.

Speaking as the president of the Officers for Justice, Ms. Williams said people should be able to ask questions to prospective police officers to see if they are good fits for the community. She also feels it’s the organization’s responsibility to be involved in recruitment of not only women, but also minorities.

The fight continues

Retired LAPD Sgt. Cheryl Dorsey and Philadelphia Sheriff Rochelle Bilal both joined their police departments in the 1980s.

Ms. Dorsey described the culture of policing as the same today as it was back then.

“It’s going to take a long time, I think, to fix this, because the problem is systemic, and it’s cultural and it’s top-down, meaning police chief down. So, while I don’t want to be discouraging to anyone, because I think clearly, we need to be on these departments and we need to be decisive and tenacious in our efforts to move up through the ranks,” she said.

“When we catch officers misbehaving, even if it’s a supervisor, we need to do what those 10 women over in D.C. on the Metropolitan Police Department have recently done, which is file a lawsuit, because really these police departments only understand one thing, and that’s civil litigation.”

Despite the challenges, several of the Black women officers encouraged others to go into policing. Sheriff Bilal said she’s training the next woman sheriff “because they had it for 181 years, and we’re not giving it back.”

She served on her city’s department from 1986 to 2013 before she ran for sheriff in 2019. She said as a Black child growing up in North Philadelphia, she didn’t like police, but she was convinced to join. She described the job as difficult but rewarding, and said reforming the justice system is a must. She encouraged women officers to “beat sexism down.”

Ms. Williams said her experiences as a Black woman are not unique to her. “I’ve spoken with law enforcement members all over the United States, from the South to the East Coast to the West Coast and other northern states. We all experience the same thing, especially when you’re Black and if you’re a female,” she said. “Even if you’re a Black male, you will get at some point a wake-up call that reminds you of who you are. You’re never blue enough, because you’re Black. When you’re Black, you’re never blue enough for your department.”

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam described sexism as an impediment to self-development. During his Holy Day of Atonement 2018 keynote address delivered at the Aretha Franklin Amphitheater in Detroit, he said, “There will never be a change in the world until women rise from the condition that male authority has put them in. Women are rising all over this planet.”